Water Mills on the Upper Colne

|

|

||

| In feudal England watermills were important franchises belonging to the lord of the manor who owned the sole right to grind corn and levied a toll on everybody using his mill. Each monastery also had its own mill which served the dual purpose of controlling the sluices to the fishponds and grinding corn.

The economic value of water-mills in the years before steam power was harnessed, was enormous. The mills were rented out to professional millers, and as valuable income producing assets, grand families collected portfolios of them. The De Veres based in Castle Hedingham are said to have had 17. Watermills had been established on nearly all the sites mentioned in this article by the time of the Domesday survey in 1086 and since the technology dates back to the The geography of North Essex does not lend itself to fast flowing rivers and the Colne is both short and undramatic. Yet by the time of Domesday there were 33 mills on the Colne and its tributaries. In what is the driest part of the country, insufficient water must have been a perpetual problem, especially in the upper reaches. |

||

| This article deals only with mills on the Colne within the CSCSI (Colne-Stour Countryside Association Sphere of Influence!) i.e. from the source somewhere near Steeple Bumpstead to the fringes of Colchester.

In 1086 all the mills would probably have been milling grain, but since wind and water were the only sources of power other than muscles, the mills were adapted over the centuries to mill oil (Wakes Colne), for fulling (Langley), for producing paper (Greenstead Green appears to be the only one, and that is on the Bourne Brook, a tiny tributary of the Colne) and, ultimately, for spinning and weaving (Halstead). Fulling was the process whereby cloth was hammered to give it more body. Before fulling it would have been possible to see through the woven cloth. Many mills were used for both milling and fulling simultaneously. |

|

|

| The first surviving mill on the Colne is Alderford in Sible Hedingham, but Domesday mentions two others higher up the river at Yeldham and Castle Hedingham. Of Yeldham there is now no trace and even in Domesday it is described as “then one mill”, meaning that there had been a mill there at the time of Edward the Confessor, but that at the time the Survey was written it had for some reason disappeared.

A 1592 map of Castle Hedingham shows the mill just behind Memories, the hideous restaurant which today decorates the entrance to the village from the Halstead – Yeldham road. The mill stream, which has now been filled in, was cut about 50 yards nearer the main road than the present bridge over the Colne and necessitated a second bridge. The mill itself belonged to the Benedictine nunnery which stood on the site of the present Nunnery farm and was founded in the twelfth century by Alberic de Vere the First Earl of Oxford; his wife Lucia becoming first Prioress. The de Veres exacted a toll on anyone crossing the bridge. The ford on the south side of the bridge, which can still be clearly seen, is called Hinck Ford, and gave its name to the Hinckford Hundred which at the time was administered by the de Veres. The only surviving remnant of the mill is a millstone set into the road outside one of the cottages in Nunnery Street. Otherwise both mill and nunnery have disappeared, although, improbably, Hinckford Hundred lives on. Nowadays the Colne in Yeldham is usually no more than a trickle and it seems unlikely that there would be enough water for a mill at Castle Hedingham, but by the time you get to Sible Hedingham the flow has picked up appreciably. There you will find Alderford Mill, a lovely example of the typical, unpretentious, white, weatherboarded, red roofed, Essex water-mill. The present mill which was built in the 18th century, is the last in a long line dating back to Domesday, and was operated by the Rawlinson family right up to the 1960’s. It was bought by Essex County Council in 1994 and they are very slowly doing it up with the intention, eventually, of opening it to the public. At present it is only open when the moon is blue, but it is also open on National Mill Day which in 2006 fell on the second Sunday in September and that is when I went. |

||

| As it was such an auspicious day, Geoffrey Wood the County Mills Officer was there to oversee things. He is a mill-wright by profession, a mine of information on all things to do with milling, and has responsibility for getting the machinery back into working order. The two main jobs still to be done are to rebuild the wheel and to equip it with a new shaft or axle. The shaft is about 2 foot in diameter and weighs approximately a ton. The new one is being made from French oak – sadly English silviculture is no longer up to the job. Give Mr Wood another 2 or 3 years and the wheel should be turning again. Let’s hope that the Health and Safety busybodies will allow us to go and see it in action. |

|

|

| Inside the mill, whitewashed to provide as much light as possible to reduce the need for naked lights, which in the dusty atmosphere might have blown the whole place sky high, there were originally 5 sets of stones. Two were operated by the wheel and a further 3 were added when steam power was introduced. Finally a diesel engine replaced steamand operated a number of roller milling machines. In the 1880’s the introduction of roller milling technology from Hungary marked the beginning of the end for the water-mills. Although wholemeal flour continued to be made by stone milling, a pair of stones could only produce about 1 hundredweight of flour an hour whereas a roller milling machine could produce about 5 times that. Outside, the mill has been beautifully re-roofed and repainted.

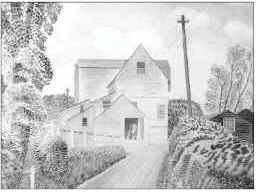

The intrepid can now walk a mile and a half or so down the river to Hull’s Mill in the parish of Great Maplestead. It is a beautiful walk and you will be amply rewarded when you get there. Hull’s Mill is the most picturesque of all the surviving mills in the Colne Valley, thanks to its glorious location, its fine state of preservation and its magnificent ford. It is well known to a wider public thanks to the watercolour by Eric Ravilious which was recently bought by the Fry Gallery in Saffron Walden for £35,000. The footpath from Alderford Mill takes a circuitous route which allows you to approach the mill from the Maplestead side down the lane from Purls Hill. Dr Ronnie Green who lives on the lane the other side of Hull’s Mill has written on it at length as “My Favourite Lane” and it is difficult to think of a more enchanting one in the whole of Essex. |

||

| Nearing the bottom of the lane it crosses the old railway, where I am always thrilled to see the notice advising drivers of the weight limit of 8 tons – except buses up to 101/2 tons. Ronnie Green says that to the best of his knowledge and that of the locals no bus has attempted the lane for the past 50 years.

Hull’s Mill is another Domesday mill and remained in operation until 1959. It was rebuilt for the last time in 1848 and from 1917-1959 was operated by Hovis Ltd. |

|

|

| Both the mill and the lane were then renamed Hovis and although Hovis had to keep up with technology and removed the wheel, which was replaced with a turbine,they were enlightened owners and kept the exterior of the mill in first rate condition. It has subsequently been converted into a rather fine house. The original and very beautiful fifteenth century mill house stands just the other side of the exceedingly narrow road. The ford on the Hedingham side of the mill always has a reasonable flow of water across it, and sometimes unreasonable. A measuring post gives adventurous motorists a good idea of what their chances of survival are.The next mill down the river, Box Mill on the outskirts of Halstead, is no more, and on the Hedingham side of Box Mill Lane you will find the recently completed barrage designed to prevent flooding in Halstead. The mill and mill house were torn down in the 1920’s, the adjacent windmill having been blown into the river in 1882. No sign now of the idyllic scene that decorated the front cover of our 2005 newsletter. All you will find is a sea of nettles which envelops one of the Colne’s most neglected stretches. Not that things were anyway always idyllic. In 1889 the miller, John Ruffle, caught his beard in the machinery and was squashed. | ||

| The other mill in Halstead, now called Townsford Mill, is the place where the Courtauld textile empire really took off, (after smaller beginnings in Pebmarsh and Bocking). The mill, a magnificent white, weather-boarded building (and now a star of television), sits astride the river in the centre of Halstead, and from the outside is very much unchanged from the middle of the nineteenth century.

There used to be constant disputes between the Town mill and Box mill over the use of water, as when the Town mill built up its working level, the water level at Box mill rose to the point that the efficiency of the mill was reduced by as much as 50%. In 1825 when Samuel Courtauld bought the Town mill, he put in a new wheel and matters ended up at the Essex Summer Assize. The jury found unanimously in favour of Box mill, but it was awarded damages of only one shilling which seems a trifle mean, since Box had found itself unable to start the day’s work until the Town mill had been operating for two or three hours and had thereby reduced the water level. Courtauld then went over to steam and the Town mill was adapted for silk weaving. A power loom factory was built in 1832 and by the 1890’s the business employed about 1400 people. Most of the factory buildings were demolished following the closure of the business in 1982, but the mill itself, one of the finest industrial buildings in East Anglia, lives on as an antique emporium and café. |

|

|

| Langley mill, the next down the river and sometimes described as the third Halstead mill, was never in Halstead but the relentless advance of factories along the west bank of the river makes it look as if it soon might be. The mill house remains, and the mill itself has also been turned into a house in rather unsympathetic yellow painted brick. This is a pity as the mill stream still runs under the house and the view from the Colne Engaine road is otherwise a very attractive one.

Just over half a mile below Langley you come to Ford Mill, also called White’s, after the miller there for the last 50 years before it was demolished in 1917. From the road you would never know that the tiny, fairy-tale house (now added on to) which probably dates back to the 16th century was once a mill house. The Environment Agency have recently done a lot of restoration work on the mill race and reinstalled the wheel, though not the mill building which used to house it (see photo). |

|

|

| Further down the river in Earls Colne, the Priory used to have a mill next to Colneford bridge on the main Colchester road. The mill which was built by the monks in about 1100, was burnt down in the early part of the last century, though the handsome 18th century mill house and part of the mill pool remain. A lease in the Essex Records Office dated 1881 from John Cawardine, the owner of Colne Priory to Henry Hills, included in addition to the mill, some stables, a brewhouse, a chaisehouse and a cowhouse. However the miller was forbidden to keep geese or swans on the river or mill pond. (This was in case he let them eat other people’s grain. In medieval times, millers, who were generally thought to be pretty unscrupulous, were limited by ordinance to three hens and a cock). The Colneford miller was also forbidden to erect or use any steam engine as the inhabitants of the priory might have found the noise injurious to their well-being. This no doubt contributed to the early demise of the mill. |

|

|

| The other mill in Earls Colne is Chalkney, well known to countless people who kennel their dogs with Sarah Coleman. The setting is amazingly secluded and the river and water meadows have a gloriously old-fashioned feel about them. The mill, originally used for fulling, was a wreck in the 1970’s, but has been most successfully restored as a pair of cottages.

Henry Hills, mentioned above, owned Chalkney, Ford and Overshot mills (the latter is on the Peb) and in the 1870’s attended in London the first exhibition at which roller mills were demonstrated. He came back and told the manager at Chalkney that “they were out of business, sure as fate”. He wasn’t far wrong. |

|

|

| The introduction of roller mills coincided with the import of large quantities of foreign wheat and sounded the death knell for the average water mill.The introduction of steam meant that water power was no longer necessary and before long all the business gravitated to rolling mills situated near ports or rail-heads.

Just over a mile below Chalkney one comes to Wakes Colne – a very different kettle of fish. The main mill building which is huge, brick and businesslike, was rebuilt in the 19th century after the top had been blown off the old mill in a dust explosion. It flanked a smaller oil mill and both have now been turned into houses. The builders of the corn mill seem to have been rather overambitious, as it was designed to operate five sets of stones but there was never enough water for more than three. It was impossible to fit in all five sets of stones without taking a considerable chunk out of the miller’s house next door which consequently had to be rebuilt. Although the oil mill (which used principally to produce linseed oil), closed in the 1930’s, the corn mill continued in business right up to 1974. Even after that, the Ashbys, (who had operated the corn mill) have continued in business as coal merchants to the present day. |

||

| Below Wakes Colne there were three more mills before West Bergholt and the outskirts of Colchester. All three mills have disappeared although the mill houses survive. The mill at Ford Street was demolished in the 1920’s but the mill house can be found just over the bridge on the opposite side of the road from the Leg of Mutton. An early 20th century photo shows the four storied mill building astride the river with a tall chimney beside it. A public footpath now runs alongside the house and the former mill race (which is lovely) until one ends up in the Mill Race Garden Centre. |

|

|

| Lower Mill at Fordham, also known as Hammonds is easy to miss, being hidden at the bottom of the hill as one comes out of Fordham on the right hand side of the road before one crosses the river. Once again the mill itself has disappeared, although photographs show the long mill building dwarfing the house which nowadays stands alone and looks uncomfortably truncated.

Cook’s Mill, the last mill on our stretch of river, disappeared in the 19th century. The site is nevertheless very much worth visiting, the fine 18th century mill house being set in truly idyllic surroundings. It is approached down a steep hill from Fordham Heath and the last hundred yards or so must be completed on foot as the public road gives out and is replaced by a footpath which runs through the gardens of the house. It is impossible to tell where the mill buildings were, but the setting is as romantic as any on the Colne. Having rashly said that I would write an article on water mills on the Colne, I soon found that I had bitten off rather more than my readers might be expected to chew. To cover my subject adequately would require an article at least twice as long as this. I have therefore deliberately not dealt with the technical aspects of milling, fascinating though they are, as they are covered in impressive detail by the late Hervey Benham in his wonderful book “Some Essex Water Mills”. |

||