ST. STEPHEN’S CHAPEL, BURES

Exterior of St. Stephen’s Chapel, Bures.

St Stephen’s Chapel stands in a secluded spot on a hill half a mile east of Bures village. It was built in the second decade of the 13th century as a manorial chapel by Gilbert de Tawny, a local landowner. We know that the chapel was abandoned at the Reformation but, mercifully, was found useful so, rather than being allowed to become completely dilapidated, was used variously as a barn (hence the local name Chapel Barn) and in 1734, as a hospital during a local plague. Thereafter, it became a school, farmworkers’ cottages; and finally a barn. In about 1918, the place was bought with the surrounding land and house by Isobel Badcock, a distinguished Victorian water-colourist. She set about laying plans with her brother-in-law, Colonel William Probert, to restore the Chapel. On December 5th 1940, the year after her death, her dream was realized when restoration was completed and St Stephen’s was re-consecrated by the Rt. Rev. W.G. Whittingham, Bishop of St Edmundsbury.

So far unremarkable, except for two things. The first is that tradition has it that St Stephen’s Chapel was built on the very spot where King Edmund was crowned on Christmas Day 855AD.

Like all good, ancient traditions the story is somewhat shrouded in mystery and has its sceptics. We know that Edmund was crowned in 855AD by Bishop Humbert of Emham because his contemporary the Welsh Monk Chronicler Asser (later Bishop of Sherborne) recorded the fact. And we hear much later from the chronicler Geoffrey of Wells, writing around 1150, that ‘Edmund was consecrated and anointed King at ‘Burum an ancient royal hill, the known bound between East Essex and Suffolk situate on the river Stour’. Burum, we can assume was a variation of the name Bures. The story is repeated by Mathew Paris writing around 1230 in St Albans, perhaps copying Geoffrey of Wells, although he does name it correctly as Bures not Burum. Or, quite probably, both Geoffrey and Mathew drew from an earlier source as Geoffrey admitted his material was compiled from what he had heard and read elsewhere. It also appears in the 1120 Annals of St Neots as “at Burna”.

We presume that the early 13th century stone chapel was the successor to an earlier wooden structure, perhaps like the 9th century wooden chapel at Greensted near Chipping Ongar in Essex. And we know that the current stone chapel was consecrated by none other than the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal of Rome, Stephen Langton, on St Stephens Day 1218.

Inevitably, the story has its doubters who point out that the Archbishop’s presence can be explained by the fact there were Langtons (presumably cousins of the great man) living in the village in the 13th century.

But these sceptics have their own explaining to do. Mediaeval hagiographies of saints were indeed famously fanciful, but why would the chronicler Geoffrey, sitting in Wells, be so very precise about a hill on the Essex Suffolk border on the river Stour ‘a river flowing rapidly in both summer and winter’. The river Stour today is quite slow but the river became an important artery of commerce in the 17th to 19th centuries and was much altered by the time of the by the banks, weirs and locks made famous in John Constable’s paintings. But the Assington Brook below the chapel of St Stephen’s does indeed, to this day, flow rapidly in both summer and winter. And would the Archbishop of Canterbury really travel all this way just for the consecration of a chapel built by a friend of his relative? After all, in 1218 Langton would only just have returned from a two year exile from England for refusing to excommunicate the barons in his long running war with King John.

So, we in Bures will continue to defend the spoken tradition that ‘the chapel in the corn’, as it was known in the 19th century, stood on the site of St Edmund’s coronation.

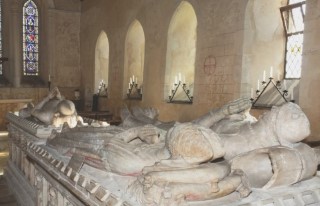

The second thing that lifts the Chapel out of the ordinary is the presence inside of three tombs of the Earls of Oxford which, as Simon Jenkins observed in his ‘1000 Best Churches in England’, are more suited to Westminster Abbey or Warwick than to a remote Chapel in Suffolk. But St Stephen’s was not where the tombs were first housed. The de Veres, who were one of the premier mediaeval dynasties in the land, chose the small Priory at Earls Colne in Essex, five miles west of Bures, and the inner sanctum of their empire, as their burial ground. It is believed that by the time of the Reformation there were 22 tombs in their mausoleum and following the death of the 16th Earl in 1563, his relict the Countess struggled on for a while. According to Sir George Buc the Master of Revels, writing in 1619 in a digression on John de Vere the 13th Earl of Oxford, the Priory was demolished and ‘all the sepulchres and noble monuments of John’s ancestors razed to the ground and the bones of the ancient Earls left under the open air. . .within six score years of John’s death’, which dates the destruction of the Priory around 1570. Fortunately, the three tombs that survive, the 5th Earl, 8th Earl and the 11th Earl and his Countess, had by then been moved for safekeeping to the Parish Church of Earls Colne.

At his father’s death in 1563 Edward, the twelve year old 17th Earl, was bundled off to London as a Ward of Court of William Cecil. By the time he was in his 30s he had run through all his money and had sold most of his inheritance, including the sale in 1583 and 1592 of Earls Colne itself to his stewards, the Harlackendens. This may have been because he was a spendthrift or because of sharp practice on the Harlackendens side or, in all probability, it could have been an injudicious mixture of the twain.

In 1629, the antiquary Robert Cotton was in discussion with Richard Harlackenden about the ten surviving effigies and engraved slabs still on site. They planned to take them from the lumber room in the remnants of the Priory and cart them by water, presumably to London. Harlakenden promised to do this subject to the 18th Earl’s agreement. Unfortunately, the plan fell through and they were left in the decaying remnants of the Priory until 1736, when they were chopped up by Harlakenden’s descendant, John Wale, to make fireplaces for his rebuild of the house at Earls Colne.

Nor were the three surviving tombs allowed to rest either. In 1825, Wale’s current descendant at Earls Colne Priory, the Reverend Henry Carwardine, who was rebuilding the house, erected a gallery outside the house into which the tombs were moved and re-erected higgledly piggedly. The family tradition was that he did so because the then Vicar was ‘improving’ the church and had threatened to bury the tombs. There they remained for 100 years until 1935. By then, Colonel William Carwardine Probert, a descendant of Henry Carwardine, had inherited Colne Priory, apparently because he had paid off the racing debts of his second cousin, Florence Keeling, nee Carwardine, who was the last of the Carwardines to live there. Probert, who had his own place at Bevills, Bures decided to sell the Priory and as he was by then in the middle of restoring St Stephen’s Chapel, effected the removal of the tombs from Colne Priory to St Stephen’s Chapel, where now they stand. Shortly afterwards, they were joined by the slab of Alberic de Vere, father of the first Earl of Oxford and the first of the line to bear the office of Lord Great Chamberlain. The slab had been found in a rock garden in Earls Colne and, in recent years, a sarcophagus was discovered in a wood at Colne Park.

So here in one quiet corner of Suffolk we have the site of the coronation of St Edmund, King and Martyr; a chapel consecrated by Archbishop Langton; and the tombs of one of great mediaeval dynasties.

Geoffrey Probert

Camilla Melville-Ross

Geoffrey Probert and Camilla Melville Ross are brother and sister and will be known to many members. Geoffrey lives at Bevills, Bures, and his estate featured in the article on Extending the AONB in last year’s Magazine.

St. Stephen’s Chapel Tombs facing altar.

St. Stephen’s Chapel Tombs seen from the altar.