An Earl’s Tower

Hedingham Castle, Essex, part I

The home of Jason and Demetra Lindsay

Fig 2: The keep lies at the centre of the vast earthworks that surround Hedingham Castle.

In the first of two Country Life articles about this great castle, John Goodall looks at the medieval development of the site and the remarkable history of the keep. Photographs by Paul Highnam.

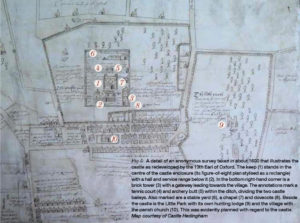

The village of Castle Hedingham stands in the valley of the River Colne in Essex. Set slightly apart from the medieval settlement, but integrally planned with it, are the massive earthwork ramparts of the castle that give the village its name (Fig 2). This castle was owned and developed by the de Vere family, which first received the Barony of Castle Hedingham soon after the Norman Conquest in 1066.

The first documented member of the family is one Aubrey de Vere, a lawyer whose service as an administrator to Henry I won the hereditary office of Chamberlain of England (which the family enjoyed until 1703). Aubrey presumably inherited a castle at the seat of his barony, but the present earthworks

probably bear the stamp of a massive reorganisation at the hands of his heir.

Aubrey was murdered during a riot in London in 1141 and his son, also called Aubrey, entered into his estates. At the time, King Stephen and the Empress Matilda were engaged in a bitter struggle to secure support for their rival claims to the throne and they wooed supporters by grants of land and titles. As a result, the number of earldoms in England—an Anglo-Saxon title invested with enormous prestige—swelled dramatically from about seven to nearly 40.

With huge resources at their disposal, the new earls sought to assume the architectural trappings appropriate to their new-found status. Abbeys and priories were particular beneficiaries of their

largesse, but so too were castles. These were practically important in the work of staking out territory, but their architecture had a symbolic significance, too.

Since the Norman Conquest of 1066, a small group of the most important castles had acquired huge towers of stone. These ‘great towers’, which we now term keeps, were viewed as prodigious works of architecture that physically expressed dominion. Prior to the Anarchy, great towers had effectively been the preserve of the king and his favoured circle. During the Anarchy, however, the new group of earls began to build them, too. East Anglia saw a particular proliferation in these buildings, many of them copying in form or detail the principal royal keep at Norwich, built from 1095 by William Rufus.

In 1142, Aubrey was offered an earldom by Matilda. In a unique grant, he was offered the title of Cambridgeshire, Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Wiltshire or Dorsetshire. He chose the second, and the last of the 20 Earls of Oxford in succession from him died more than 550 years later.

There is no documentary evidence to date the tower at Castle Hedingham, but the case for associating it with his earldom is compelling. It is significant, moreover, that its architectural inspiration comes not from Norwich, but from the south-east of England, almost certainly a reflection of William’s connections with London.

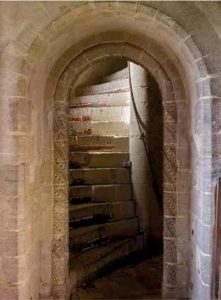

Fig 1 : The impressive main entrance to the medieval keep.

The tower was laid out on a square plan with massive walls about 12ft thick and rises to a height of about 100ft, the benchmark measurement of a medieval skyscraper. It is faced with beautifully cut blocks of limestone from Barnack in Northamptonshire and, as another mark of quality and expense, incorporates richly carved architectural ornament, including chevrons or zigzags (Fig 1). Even the plinth from which

the whole structure rises is delicately moulded, an extraordinary extravagance.

There are five storeys within the tower, one more than is usual in buildings of this type. Indeed, this treatment has only one extant 12th-century parallel in England, the leviathan keep erected from 1127 by the Archbishop of Canterbury, at Rochester, Kent. The resultant tall and narrow proportion of both buildings sets them apart from the mainstream of great towers, most of which are broader than they are high. As originally completed, the five storeys of the building were divided internally to create three floors: a basement, a first floor and a double-height second floor. The uppermost storey enclosed a pyramidal roof countersunk within the parapets, where its drains and the scars of leadlines can still be seen. At some uncertain point in the later Middle Ages, a low-pitched lead roof was erected at the top of the building, creating an extra floor in this former roof space. The thick tower walls are laced with short passages and small chambers. These include latrines with chutes that empty into the basement, an arrangement that would have required intensive management if the whole building was not to stink. It has only one known parallel, at Rochester. The central wall rising through the tower at Hedingham Castle also divides the structure in two. It is pierced at first and second-floor level by vast arches. (Fig 3).

Fig 3: The main interior of the keep with its fireplace, internal arch and encircling gallery.

Notches cut in the upper arch show that it was at some point infilled with a timber framed wall, possibly around 1500.

Fig 6: the gallery on the third floor is accessible from a stair in one angle of the tower.

It is frustrating to have no information about how this extraordinary building was used in the 12th century. There are no kitchens or small withdrawing chambers to suggest daily domestic use. Rather, the great upper hall might plausibly have been used for ceremonial events. It is intriguing in this respect that the gallery running round the upper storey of the principal interior is entered through a door carved with decoration only on one side (Fig 6). This may imply a correct way of entering and walking round the gallery. The tower was originally entered up a timber stair fixed into the side of the building. Very soon after its completion, however, this was replaced by a staircase tower. Visible in the external masonry of this are the lines of roofs that, at different times, covered the stair (Fig 4). There is also a semi-circular scar to the left of the main door, the setting for a vault over what was presumably a chapel at the head of the stair. The stair has recently been repaired with the generous help of the Country Houses Foundation.

Fig 4: The exterior of the keep is finished in cut blocks of limestone. In the foreground are the ruins of the staircase tower to the building. The scars of its former roofs are visible, as is the semicircle of the chapel vault to the left.

Today, the tower stands in isolation, but a cluster of medieval buildings— including a hall and chapel, possibly connected by cloister walks—stood to the west of it on a slightly different alignment. Their foundations were excavated in 1868 and have been recently surveyed using modern archaeological techniques. It is very difficult to date these foundations accurately or unpick their evolution in detail.

No less complicated to understand is what happened to the castle in the 200 years or so after the completion of the great tower. The de Vere family fortunes were mixed and, during the Wars of the Roses, loyalty to the Lancastrian cause brought disaster. This was abruptly turned to advantage, however, at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, where John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, commanded Henry Tudor’s vanguard. In the aftermath of the victory, the Earl enjoyed exceptional standing in the new Tudor regime and invested heavily in architecture.

One of numerous buildings that benefitted was Hedingham Castle, which, according to the antiquarian John Leland, he largely reconstructed before his death in 1513. The new buildings, including a second tower overlooking the village and great hall, were executed in brick and green terracotta. All that survives from them is a bridge connecting the two castle baileys. Nevertheless, a sense of the building and its wider setting with parks is provided by early surveys and drawings (Fig 5).

The castle created by the 13th Earl was visited by Elizabeth I in 1561 and her host, John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, died there the following year. His son, the courtier and poet Edward, squandered his entire patrimony before his death in 1604. According to one estimate he raised more than £40,000 from the sale of some 86,000 acres of land, 64 manors and four castles, including HedinghamCastle. A survey of 1592 describes the recent demolition of several castle buildings by his warrant.

It is possible that the buildings underwent repairs in the early 17th century, following the purchase of Hedingham Castle in 1610 by Edward’s second wife, Elizabeth Trentham, for her son, the 18th Earl of Oxford. Or following its reversion to the Trentham family in 1625, when the association of Hedingham Castle with the de Veres was finally broken after five and a half centuries.

Nevertheless, the castle played no significant role in the Civil Wars of the 1640s and a drawing of 1665 suggests that the buildings were derelict. In The History and Antiquities of Essex (1816), Philip Morant asserts that, in the following year, 1666, the buildings were deliberately ruined to prevent the castle being used for the accommodation of prisoners of war.

In 1713, the castle and its estate were sold to Sir William Ashurst, whose new house on the site we will examine in part 2. To judge from depictions of the building, by 1719—and possibly in connection with Ashurst’s work—all the medieval buildings or their remains apart from the keep had been cleared. Ashurst nevertheless repaired the keep, inserting within it new floors and a roof. he also apparently punched two openings into the basement, perhaps as garden features. His changes to the buildings are anecdotally transmitted through the writings of several generations of the Majendie family, who inherited the property by marraige in 1783.

The first of these, Lewis Majendie, commissioned a detailed survey of the building involving the antiquarian John Carter and the architect Henry Emlyn. Publlished in Vetusta Monumenta (1796) this must have been known to the architect Thomas Hopper, who created Penrhyn Castle from 1821, a spectacular Regency evocation of the Hedingham keep, replete with its plinth mouldings.

Fundamental to the 19th-century understanding of the keep was the 1592 survey of the castle and its associated documents, which were bound together in a volume held by the family (and once sensationally stolen from the Atheneum).Crucially, these mention an ‘armoury’ within the building and,as a consequence, the main chamber of the building assumed this name. The Armoury was occasionally used for entertainment, most notably for Henry VII in 1498 and for a dinner to honour Benjamin Disraeli in 1849.

It was also furnished with appropriate contents and historic furniture. This collection fell victim to a disastrous fire caused by an army stove on the roof in 1918, at a time when the keep was occupied as an observation post. In 1916, the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments had published a survey of the building.

In October 1918 the architect William Weir, a specialist in work to ancient monuments quoted the cost of repairs at £2,200. Just prior to the reinstatement of the walls and floors, COUNTRY LIFE photographed the keep as a ruined shell, later publishing the pictures.(COUNTRY LIFE, September 25, 1920.)Weir’s restoration was restrained and dignified, preserving all the original plasterwork and detailing.

Since 2013, the present owners of the castle have transformed the interiors he created into a wedding venue.Their work has ben as ingenious as it is sensitive. A new hardwood floor (made from salvaged planking from Southend pier)has been laid in the basement and the 1720s openings used to make the space wheelchair accessible. Fabrics have been hung to soften the interiors including homemade curtains basement decorated with the arms of the barons of Magna Carta.

There are also ingenious fittings that make the interiors functional, such as hinged fabric screens and basins disguised within barrels. Modern services have been run through areas of concrete laid in the 1920s restoration of the building. the Lindsays’ inventive approach has also extended to the Georgian house as we shall discover in Part 2.

For further information, visit www.hedinghamcastle.co.uk