‘The Haunted House’ of Lamarsh – Some Early Reflections

‘A delightful Georgian Country Residence, with a most attractive Tudor wing at the rear’ ran the estate agent’s blurb. ‘Price with 18 acres of land and a farm cottage, £16,500’. Such was the description of Daws Hall when I acquired it in 1965, when the total number of cars in Lamarsh amounted to three, four years before the first man was to step on the moon, and many years before websites and all that goes with them were to start dominating our lives.

Most exciting for me, since I was planning to establish a wildfowl farm, was the presence of a good sized pond and several springs. We were, however, somewhat disconcerted to be told that at least two people from the village had committed suicide in this pond and that, at one time, it had been the site of a gruesome murder. According to the old poem which I now have,

‘Once on a time, long years ago, Two hundred, may be more,

A gallant knight and a ladye faire Passed through the oaken door’

They were obviously a hospitable couple, for

‘Many came, from foreign shores To dine and sup with ease.

Amongst the strangers there was one From far off sunny Spain.

He lingered long, then went away, But to return again.

He’d heard it said that untold wealth In that old house was stored,

And meant by skilful searching, To find that rumoured hoard.

At length, one night, he ventured forth, Success was his at last,

(or so he thought), when suddenly A figure by him passed.

It was the ladye, who had seen Him stealthily creep forth, And guessing his intentions Had dared to face his wrath.

When he found he was discovered, His fury knew no bound,

He seized her by her golden hair, And threw her to the ground, Then down into the garden

He dragged his victim faire, And threw her in the lily pond And left her lifeless there. And now,’tis said, her spirit Still hovers round the spot, And people say they see it,

It may be so, or not.

At any rate, the ‘Haunted House’ For years has empty been,

The garden is neglected And ruin reigns supreme…’

Being the owners of a ‘haunted house’ was certainly a novel experience. Personally, I had always considered ghosts to be figments of the imagination until, fairly soon after moving in, we had more than one ‘experience’. First, there was a distinct smell of burning in the kitchen, where there were still a few charred oak beams on the ceiling. This was always in November, which we took to be the anniversary of when, around 1780, the old part of the house had been burnt down, before being replaced with a late Georgian front. Then, when various objects in the house kept being found to have mysteriously moved, it seemed that we had a resident poltergeist. Then again, we kept hearing a mysterious ghost dog walking on what sounded like rush matting along the downstairs passage. This was not entirely unexpected, as the previous owners had told us that on one occasion a guest of theirs had had a very clear sighting of what could only have been a ghost whippet. Also, three different generations of their dogs had howled at night and had never gone back to their baskets in one particular part of the house. They also told us that many of the local residents were so frightened of ‘the haunted house’ that, if they missed the bus back from Sudbury to Lamarsh on market days, they would take the longer route via Bures to avoid having to pass it.

Finally, at around 9 o’clock one morning, when the last thing on my mind had been supernatural beings, I happened to look up to the attic window and had a momentary but very clear view of a woman with long fair hair looking down at me. Was this the poor lady who had been murdered? Somewhat to my disappointment, apparitions, both human and canine, have for a number of years now been conspicuous only for their absence.

A few years after moving in I was delighted to have the opportunity of buying some extra land, which extended our property to the Stour and to Pitmire Island, home during the days of barges to the Pitmire lock-keeper and his family. This was before some well-meaning idiot had released all the four-legged occupants of the local mink farm, so water voles were then still a common sight along both the Stour and the Losh-house Brook. Coypu were still present and otters, though declining in number due to man’s unwarranted interference with our waterways, were very scarce. Once I was walking with my dog close to the river and she put up a bitch otter and cub which, I soon found, had their holt under the roots of an old crack willow. They must have been one of the few surviving wild otters before the start of introductions to the Stour and elsewhere by the Otter Trust.

I remember another occasion – it must have been around 1970 at a time when the word ‘conservation’ was hardly known (let alone practised), when an earnest young man from Anglian Water Authority came to see me and said that he and his colleagues would be interested to hear my reaction, ‘as a conservationist’ to a novel idea that they had of eliminating the regular flooding that occurred along the Stour between Sudbury and Bures. ‘Oh, yes’, I remarked, somewhat unenthusiastically, ‘do tell me about it.’ ‘Well’, he said, without batting an eyelid, ‘some of our engineers have had this brilliant brainwave, and that is to fill in the existing river and create a new straight waterway. You know, like a canal’, he added as he saw the look of utter astonishment on my face.

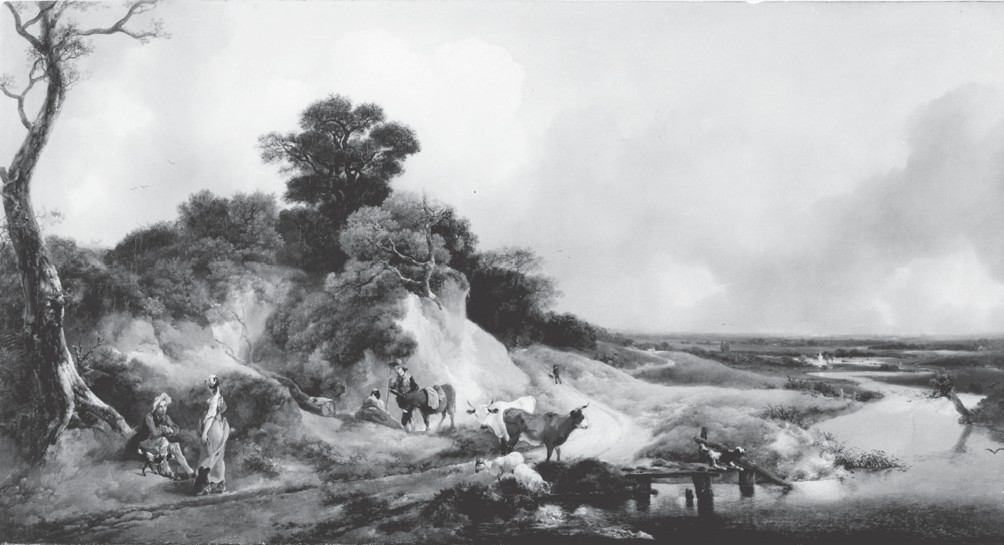

Thomas Gainsborough ‘A Distant View of Cornard’

The embankment on the left, which is now part of our nature reserve, is an old river cliff that was eroded by a much larger River Stour about 20,000 years ago. (Original in Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh).

Mercifully, this ‘brainwave’ never progressed, but what they did do, despite strong opposition from me, was to build hideous embankments along much of this stretch of the river. To create these they had to excavate valuable reedbeds and other accompanying flora and fauna which, forty years later, have still not fully recovered. (I remember the startled look on the face of one official when I told him that, if they came on to my land, the bulldozer would get my right barrel and, if that failed to stop him, the driver would get the left one). The banks did indeed act as a barrier against minor flooding, but of course the big floods went over the top and the water was then unable to recede as it had done for centuries. On one occasion, following a big flood, I found scores of fish splashing around in puddles unable to get back to the river. John Constable, who incidentally painted this house and our stretch of the Stour shortly before the fire, must have been turning in his grave.

Birdlife in the 1970s was then very diverse. Barn owls were an everyday sight hunting along the valley. Yellow wagtails, grasshopper warblers, tree sparrows, willow tits and even the

occasional bittern could all be seen, and there was always the chance of some rarity. One such example was a purple heron, regularly recorded in Holland and an occasional visitor to Minsmere and elsewhere on the coast but rare inland. Living as I do on the boundary between Essex and Suffolk, and not wishing to favour one particular county, I duly reported this sighting to bird groups in both. Back came the predictable queries ‘which county was it in?’ My response to both: ‘It was standing in the middle of the Stour with its legs apart.’

All of this took place many years ago and now, as I approach my eighty-sixth year, Bunny and I find ourselves presiding over a well-kept nature reserve and schoolroom, and having the pleasure of seeing hundreds of schoolchildren from Essex and Suffolk hopefully benefitting from what has been created over the past forty years. One of the most rewarding things for us is talking to young families on open days, and hearing from the parents how they themselves not only fondly recall coming here as children – they said it was “the best day in the week” – but also remember the vital lessons that they learned from our teachers. Incidents such as these make it all the more important to us that we do all we can now to keep the Daws Hall Trust going for many years to come.

Under the terms of our initial agreement Essex County Council paid the salaries of our two teachers and gave us a substantial grant. This support from the Council came to an abrupt halt in 2010. Since then, despite the money that, as a registered charity, we receive from grant-giving trusts and private donations, we are running at a loss. To help swell our numbers and our coffers we have recently set up ‘Friends of Daws Hall’. I am sure that we have many well-wishers among the members of the Colne-Stour Association, to whom I say ‘Do, please, support us if you can’. For further details please write to: Daws Hall Trust, Lamarsh, Bures, Suffolk CO8 5EX, or e-mail info@dawshallnature.co.uk

Iain Grahame

Iain and Bunny Grahame have been regular contributors to the magazine.