Medieval Graffiti: the hidden histories…

Today, graffiti is seen as something that is destructive and anti- social, and certainly not something that we would want to encourage in the historic buildings of our region. However, medieval graffiti left by members of local church congregations is now the focus of a project that is, quite literally, rewriting some of the history books. The Norfolk and Suffolk Medieval Graffiti Surveys are recording many thousands of previously unknown medieval inscriptions, and in the process revealing a long forgotten hidden history of the medieval parish church. The multi-award winning survey, first established in Norfolk a little over five years ago, is part funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The actual surveys themselves are entirely undertaken by volunteers, and the project has already made a number of nationally important discoveries, and recorded inscriptions in our local churches that date all the way back to the twelfth century.

The study of medieval church graffiti is really nothing new, and has been quietly going on since at least the late nineteenth century. For the early researchers though things were far from easy. To record medieval graffiti meant either taking rubbings of each individual inscription, something which is no longer encouraged, or taking traditional photographs, all of which had to be expensively developed in a laboratory. A church containing several hundred inscriptions could soon lead to significant expense on the part of the researcher – and with Norfolk and Suffolk alone containing over a thousand medieval churches, those costs would soon become quite crippling. However, the introduction of affordable modern technology, in the form of cheap digital cameras, has suddenly made it possible to undertake large-scale surveys at very little cost, and the results have been really quite impressive. In the last five years the volunteers have discovered over 28,000 early inscriptions in Norfolk alone, with almost as many being recorded in Suffolk. In almost every single case, these inscriptions have never before been recorded. It is, put simply, an entirely new and unstudied source of medieval history. And what the volunteers are finding is really quite remarkable.

The walls of our medieval churches are covered in a very different form of graffiti than that which you might expect. Here you won’t find too many examples of ‘Kilroy woz ere’, or ‘Jon luvs Angie’, but instead a parade of medieval ships, mythical beasts, jousting knights and prayers for the long, long dead. Medieval demons gambol across the wall pursued by hunting hounds, heraldic shields jostle for space amongst the leering laughing faces, and birds take flight across the stonework. All of the medieval world is to be found etched into the very stones of our churches, and the hopes, fears, dreams and dreads of the medieval mind are writ large on the wall. However, of all the many thousands of graffiti inscriptions that are being discovered, one particular type appears time and time again. It would appear that whatever church you enter, whether in darkest Essex or far away Northumberland, if early graffiti is present then the chances are that one of the first things you will stumble across will be a ‘Witch Mark’.

These markings, also known as ‘ritual protection marks’, were designed to serve a single purpose – to ward off evil, ill-fortune and, most particularly, the ever present effects of the ‘evil eye’. One of the most common type of witch mark is the compass drawn designs, sometimes referred to as ‘hexafoils’ or ‘daisy- wheels’, and these can be found in churches all across the region. Fine examples are to be found at Kedington, Finchingfield, Clare, Bures and Wormingford, but the chance are that if you come cross a church that contains any early graffiti, then at least one of these compass drawn designs will be present. However, one of the most common designs to be found etched into the walls of our medieval churches may strike many people as being a little strange – perhaps even sinister…

The five pointed star, or pentangle, is today largely thought of as being associated with witchcraft, black magic and devil worship, and yet it is to be found all over the walls at churches such as Bures, Stoke-by-Clare, Finchingfield and Clare. If such symbols are stumbled across by the odd unwary churchwarden they can certainly come as a surprise, and in some cases lead to accusations of dark magical practices having taken place within the building. However, what few people today understand is that the pentangle has only become associated with witchcraft in relatively recent centuries. Prior to that, and most particularly during the Middle Ages, the symbol was thought of as being wholly Christian in nature, and it is one of the few ritual protection marks for which we have any written evidence. This unlikely evidence is contained in the fourteenth century Arthurian poem ‘Gawain and the Green Knight’; which tells the story of the young knight’s quest to hunt down his supernatural enemy. The unknown poet states that Gawain had a golden pentangle painted upon his shield, and goes on to explain that the motif represented the ‘five wounds of Christ’, the ‘five virtues of the knight’ and was a symbol of ‘perfection’. Given such clearly stated associations with Christian imagery it really is hardly surprising that we are finding numerous examples carved in to church walls across East Anglia, and clearly indicates the spiritual nature of much of the graffiti that is being recorded.

What many people new to the study of medieval graffiti find perhaps most surprising is how little of the graffiti is actually the written word. Whilst the majority of modern graffiti tends to be text in some form or other, over ninety percent of the earlier inscriptions are pictorial. Medieval text, perhaps reflecting the lower levels of literacy during the late medieval period, is a rarity. However, there are still many surprisingly fine examples to be found in the region at sites such as Belchamp Walter, where the names of long dead parishioners are to be found carved into the door surround beneath the tower arch. A few miles north at Cowlinge Latin prayers are carved into the stonework, alongside a mass of other medieval imagery. However, there are a handful of churches, and they are rare, where there are almost as many text inscriptions as there are images. At Lidgate church the pillars are covered by an absolute mass of early graffiti, including an unusually large number of neatly written text inscriptions. Whilst not all of the inscriptions have yet been deciphered, and some are in such poor condition that this may never be possible, what can be made out is absolutely fascinating. On the pillar nearest to the south door is a tiny Latin inscription that translates as ‘John Lydgate made this, with licence, on the feast of saints Simon and Jude’.

Although not as widely known about today, John Lydgate was one of the literary celebrities of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. A near contemporary and great admirer of Geoffrey Chaucer, Lydgate’s poetry is perhaps better known today for its length rather than its quality. However, at the height of his fame he was commission by royalty and representatives of many of the most ancient noble families of medieval England. Little enough is known about the man himself, except that he spent most of his life in the nearby monastery at Bury St Edmund’s, and that he was born and brought up in the humble parish of Lidgate. Was this inscription then created by ‘the’ John Lidgate? Is this one more surviving piece of text by a medieval

literary superstar? Well, we can never really be certain. All we really can say is that it is the right name, in the right place, at the right time – and created by someone very used to using Latin and the writing arts. Beyond that, no matter how great the temptation, we really cannot go.

Whilst the walls of our beautiful churches can occasionally be found to contain the names of our medieval forebears, it is far more common to find yourself looking at images of people upon the walls. If you stare at the stonework hard enough, you’ll often find the stones staring right back at you. In almost every church that contains early graffiti you will come across faces, portraits and even, at sites such as Kedington, full length figures of elegantly dressed medieval men and women. At Stoke-by-Clare a series of little faces are to be found cut into the wall’s surface, each either shown singing or playing a musical instrument. Although several are now quite worn and degraded, it is thought that they might represent members of the medieval choir, or perhaps musicians associated with one of the many festivals of the medieval church. And very, very rarely it is possible to discover the actual music that this long departed choir may have sung. Although one of the very rarest type of graffiti inscriptions to be found, medieval music has been recorded at many of the larger sites such as St Albans and Norwich cathedrals, and even more rarely in smaller parish churches such as Steeple Bumpstead and Lidgate. This doesn’t of course mean that music was any less important within the smaller parish churches than within the monumental cathedrals. It is simply a reflection of the fact that music in the medieval parish would very much be taught in a more personal one-to-one manner, with the teaching of more formal musical notation largely confined to the larger monastic establishments. It is no coincidence that many of our still famous singing schools are still to be found attached to medieval cathedrals.

Alongside the imagery of the lower orders of the medieval world are occasionally to be found those of the very highest. A large number of inscriptions have been recorded that are clearly related to the nobility and their heraldry, with heraldic shields and armorial crests being found at many churches. These can range from the simple stylised shields at Finchingfield and Belchamp Walter, to elaborately carved coat of arms at churches such as Troston. At a few sites such as Worlington, close to the Norfolk/Suffolk border, detailed inscriptions of heraldic lions and other beasts are clearly depictions of known coats of arms, whilst others at sites such as Bures are far more generic in nature. Exactly who created these inscriptions, as with so many other types of early graffiti, is unclear. Were they created by the nobility themselves, or by the lower orders seeking to emulate them or show some form of allegiance? Again, it is likely that we will never know for sure. What is clear is that these graffiti inscriptions appear to reflect many aspects of medieval life, and sometimes produce as many questions as they do answers.

From an archaeological perspective these discoveries are a fascinating insight into the real lives of those people who lived in the medieval parish and worshipped in the village church. For the vast majority of the medieval parish, the church building was the focus for both their social and religious life. It was a symbol of local pride, of Church authority and religious salvation. The church building formed the central core of parish life. For the common people of the parish, life within the community began at its font, marriages took place within its porch and vigils for the dead were watched beneath its roof. And yet, despite playing such a fundamental role in the rights of passage of countless generations of commoners, we still know very little of how these individuals, the vast majority of the medieval congregation, actually interacted with the church on a physical level. Their voice is a largely silent one.

In the majority of areas of medieval history the evidence that survives tends largely to relate to the elite. The interior of the surviving churches, their stained glass, alabaster tombs and monumental brasses tell us only about those who created them or caused them to be created. In most instances this is either the upper classes of the parish or, in the case of larger institutions, the nobility of the surrounding locality. They evidence trends and styles, the hopes and ambitions, of those in a position to cause such lasting memorials to be fashioned; quite simply, those who had the money to buy the immortality of alabaster. Where here then is the voice of those who worked the parish land, who worshipped in this splendid monument to their betters? Where then can we find a voice for the commonality of medieval England?

This then is perhaps the most unique aspect of the discoveries being made by the surveys: the surviving images and inscriptions cross the boundaries of wealth and class. They can have easily been created by a commoner, priest or nobleman. They can have easily been inscribed by man, woman or child. In this they are unique and, as such, they can be regarded as truly reflecting the hopes, fears, humour and ambitions of the people of the medieval parish.

Matthew Champion

Matthew Champion is a freelance archaeologist and is currently Project Director of the Norfolk and Suffolk Medieval Graffiti Surveys. His latest book, ‘Medieval Graffiti: the lost voices on England’s churches’, was published by the Ebury Press in July 2015.

1. Lidgate Church

2. Lidgate Windmill

3. Lidgate Music

4. John Lydgate

5. Lidgate Circle

6. Bures Compass Drawn

7. Belchamp Walter Shield

8. Finchingfield Dragon

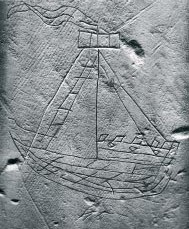

9. Cowlinge Ship

10. Worlington Shield

11. Troston Shield

12. Clare Pentangle

13. Kedington Figure

14. Kedington Sword

15. Cowlinge Text

16. Wormingford

17. Stoke by Clare Figure

18. Stoke by Clare Figure