HOLD FARM, BURES ST MARY; A RARE TUDOR WATERMILL

This article is an abbreviation of a report prepared by Bures-based architectural historian Leigh Alston for English Heritage in 2010. Thanks due to the owners, Mr and Mrs Tom Hills.

Hold Farm from the south, showing the truncated eastern end of the Tudor mill to the left.

Summary

Hold Farm is the earliest secular watermill in Britain and merits listing at grade II* or grade I. It is currently listed at grade II as a ‘former farmhouse, said to have been a flax mill’. Medieval and Tudor watermills are exceptionally rare, with fragmentary examples surviving at four or five monastic sites in the country (including Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire and Abbotsbury Abbey in Dorset), and Hold Farm is of national importance. It illustrates the standard layout of early mills, which typically straddled their mill streams and required a separate wheel for each pair of stones before the advent of multiple gearing in the 17th century. The isolated building lies in open countryside alongside the Assington Brook, which flows into the River Stour 750 metres to the south, and may occupy the site of the ‘molendinum de Smalebrug’ mentioned in a document of 1090. The remains of Smallbridge Hall, the Tudor brick mansion of Sir William Waldegrave, to which the present mill and much of the parish belonged in the 16th century, lies on the northern bank of the river 1 km to the south- east. The original structure consists of a brick ground storey with a timber-framed upper storey in five bays and an intact crown-post roof. A pair of finely moulded brick arches in the front and rear elevations framed the mill race which passed through the building and drove a pair of wheels within (the water diverted upstream from the nearby brook). The framing of the upper storey is largely exposed and contained roll-moulded window mullions designed for external display, although the internal timbers are plain and utilitarian, but much of the brickwork is now hidden by modern render. Photographs taken during the extensive renovation and extension of the building in 1988 reveal evidence of additional arched doorways and large windows. The building continued further to both east and west (beneath the gravel drive and the eastern extension of 1988) but was truncated after its conversion into a farmhouse during the 17th century. The front (southern) range is an addition of the mid-19th century. Excavations of 1993 uncovered substantial foundations to the west but unfortunately the importance of the site was not recognised in 1988 and the opportunity to excavate elsewhere was not taken. The currently proposed alterations to the eastern extension may exposure more archaeology during any necessary groundwork, and the proposed unblocking of an original window may reveal additional moulded mullions.

Illus. 1. Hold Farm from the south in the dry summer of 1994, showing the course of the mill stream which formerly passed through the building as a green line on the lawn.

Illus. 2. The twin Tudor arches of the mill race seen from the 19th century southern extension. A pair of water wheels lay side-by-side between the arches, each driving a pair of grindstones to right and left as shown in figure 1 below. Note the fine hood moulding, which preserves traces of original red pigment.

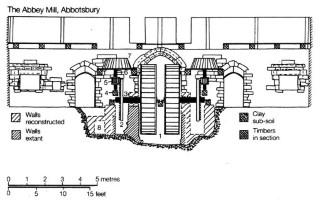

Illus. 3. The grade I-listed 14th century mill at Abbotsbury in Dorset, which provides a close parallel, although as it is embedded in sloping ground its two wheels were overshot (the water delivered from above) and it lacks an arch in its rear

Reconstruction of the Abbotsbury mill, showing the two wheels of the central mill race and the stones on both sides. Note the symmetry of the building, which might have been expected at Hold Farm. Published in the ‘Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society’, 1986, and reproduced in ‘The Mills of Medieval England’ by Richard Holt, 1988.

In the following analysis, which describes the origin and development of the building in more detail, any technical terms in Italics are defined in the accompanying glossary. Detailed plans and elevations are provided in the Appendix.

Historic Fabric

Hold Farm lies in the shallow valley of the Assington Brook 750m north of its junction with the River Stour. The building occupies an isolated location in open countryside between the village of Bures St Mary 1.25 km to the west and the remains of the Elizabethan brick mansion of the Waldegrave family on the northern bank of the river 1 km to the south-east. The structure is approached by a dedicated track from the lane between Bures and Nayland to the south, and consists of an early- 16th century rear (northern) range with a 19th century ‘double-pile’ addition to the front and a large new cross – wing of 1988 to the east.

The house is shown with its present outline on the first edition 25 inch Ordnance Survey of 1886 (omitting the modern cross-wing), but a Smallbridge estate plan of 1849 lacks the southern extension and shows the rear range extending substantially further to the west. The building was evidently truncated as recently as circa 1860 when the farm yard was completely rebuilt. Excavations of 1993 revealed massive 16th brick century foundations beneath the gravel drive, and evidence of the rear projection (perhaps a large chimney) which is also clearly shown on the 1849 plan. These foundations did not extend beneath the lawn and appeared to terminate in a timber- framed gable which lacked foundations of any kind.

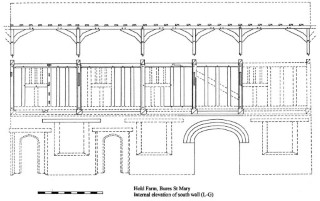

Internal elevation of the south wall (L-G).

The 16th century range contains a brick ground storey with a timber-framed upper storey in five bays on an approximately east-west axis and extends to 14 m in length by 4.75 m in overall width (46 ft by 515.5 ft). The walls of the lower storey are 45 cm thick (18 ins) producing an internal width of just 3.8 m (12.5 ft) at a time when a domestic house of any quality would normally exceed 5.5 m (18 ft). The upper storey was initially open to its roof of plain crown-posts with cranked purlin braces, and divided into at least three chambers. The crown-posts of the present gables (i.e.trusses A-G and F-L as indicated on the ground plan shown in the Appendix) contain pegged mortises for external braces, proving that the 16th century building continued further to both east and west, and the first-floor framing of the eastern gable (F-L) contained an arched door head until it was destroyed in 1988. A similar doorway existed in truss D-J (indicated today by a gap in the empty stud mortises of its tie-beam) while the remaining trusses of the upper storey were open. The ground floor was ostensibly undivided, although the mill race between the brick arches would have provided a barrier, and contained a utilitarian ceiling of plain, unchamfered joists. An arched doorway was uncovered and photographed in the southern elevation of bay J-K in 1988, but subsequently hidden, and a similar door must have existed in bay K-L where the ceiling contains an original framed stair trap. The upper storey, which presumably operated as a grain store, was evidently reached by an external stair in the usual manner of warehouses and agricultural granaries elsewhere, but was also accessible by a first-floor loading door in the northern elevation: this is now blocked, but its presence is indicated by an absence of both stud and window mullion mortises in bay C-D.

Illus. 4. Western bedroom of upper storey showing the open truss B-H with the foot of its central crown post beneath the 19th century ceiling. The re-set roll-moulded mullions in bay B-C (above the mill race) are visible to the left, and the position of a blocked original window which may retain similar mullions to the extreme left. The walls of the en suite bathroom are partly modern, but 17th century partitions survive above the tie-beams.

Illus. 5. The whitewashed plain crown-post of truss B-H seen from the east (now covered in green wood preservative) with the remains of a 17th century lath-and-plaster ceiling beneath the horizontal collars. This ceiling survives in better condition elsewhere.

The positions of the ground floor windows are indicated today by recesses in the modern render, but a pair of roll- moulded timber mullions survives on the upper storey in the northern elevation of the wheel bay B-C. These have been truncated and re-set (probably in 1988) but seem to be original; the presence of rectangular mortises elsewhere indicates the mullions were certainly moulded in the usual manner of high-status merchant’s houses rather than the diamond mullions found in most contemporary buildings. It is possible that moulded

mullions also remain in a blocked original first-floor window in the northern elevation of bay A-B; great care should be taken to avoid damaging historic fabric if this window is re-opened as part of the currently proposed alterations to the property. While the interior was undecorated, the mill’s exterior was highly ostentatious, and the arches of the mill race were chamfered and hood moulded in the latest Tudor fashion. The arches were pointed to a smooth surface and painted with red-ochre to resemble stone, while the brickwork of the vertical jambs was incised and painted to create a perfect bonding pattern. This technique was applied to most 16th century brickwork, and would have extended across the entire building; it was intended to disguise the irregularities of pigment and texture in the individual bricks of the period. The southern arch is well preserved within the 19th century extension and its extensive red ochre is of considerable historic importance.

Illus. 6. The original door arch removed by the previous owner from the eastern gable (F-L) in 1988, photographed by the author in 1992.

While the mill’s layout was probably typical of medieval watermills, as discussed below, its expensive brickwork and ostentatious exterior suggests it was designed as much to reflect the wealth and status of its owner as for normal commercial or domestic purposes. The crown- post roof and the relatively steep arches suggest a date at the beginning of the 16th century, and the brickwork is strikingly similar to that of the large chantry chapel added to Bures church by the Waldegrave family in 1514. At this period the Waldegraves were among the most important families in East Anglia, having acquired Smallbridge Hall and most of the parish during the late- 14th century. Sir William Waldegrave entertained Elizabeth I at the hall on two separate occasions in the 1560s and 1570s, and might well have taken the opportunity to show off the impressive watermill serving his large estate. The present hall is a mid-16th century fragment with a typologically later side-purlin roof than the crown-post structure of Hold Farm.

By 1680 the mill had been converted into a farm known as The Hold Farm or Russells Farm (see below). The present internal partitions of both the upper and lower storeys date from this 17th century conversion, although the first-floor ceilings and part of the central bathroom are insertions of the 19th and 20th centuries respectively. The whitewashed lath-and-plaster of the higher 17th century ceiling still survives in the roof-space (nailed to the rafters and the soffits of the collars). The whitewash of this ceiling and the crown-posts has recently been extensively spattered with green timber-preservative (it was not present at a previous inspection in 1992). The blocked trap in the ground-floor ceiling above the mill race may relate to a 17th century chimney which has since been lost, but this is not certain.

Operation of the Mill

Contrary to popular belief, medieval watermills often lay on small watercourses rather than major rivers as their waters were easier to divert and control. In a region with few steep hills and torrents it was necessary to dig lengthy channels known as ‘leets’ to create a sufficient headwater to drive a wheel. It was not possible to gear more than one pair of stones to a single wheel until the 17th century, and early mills required as many wheels as they possessed pairs of stones. The main mill in the village of Bures contained three wheels in 1439 used respectively to grind malt, grain and a set of cloth fulling hammers. The Abbey mill at Abbotsbury in Dorset, which provides the closest parallel to Hold Farm, retains two wheel pits in a single, central race as shown in figure 1, and similar archaeological evidence may await discovery here. It was sensible to combine pairs of wheels in this manner in order to drive as many stones as possible from a single channel (as each channel was expensive to dig and maintain), and mills often straddled their races accordingly. Additional external wheels and races might adjoin each gable. This practise was no longer necessary after the 17th century when a single wheel could power six or more pairs of stones. The local legend that Hold Farm was used as a flax mill may have some basis in reality, but flax was always a very minor crop in the Stour valley and the milling of grain and malt would have been its primary (and probably only) purpose.

Illus. 7. Detail of the hood moulding and smooth pointing of the arch, which contrasts with the scored joints of the vertical jambs and gave the impression of a red stone arch on pencilled brickwork (i.e. brickwork painted with a bonding pattern). The internal surfaces of the two arches were unpainted and crudely finished in contrast.

The farmhouse lies at the southern end of a narrow water meadow between the sloping arable land to the east and the Assington Brook to the west. The steep lynchet (bank) which marks the junction between the meadow and arable land can still be traced in the modern lawn to the north and south of the house, and clearly ran through the wheel race. In all probability the builders of the mill deliberately placed it over the boundary ditch and used it as a ready-made leet to avoid the cost of digging a new channel (although it was probably deepened). By using sluice gates to divert the brook into the ditch – perhaps several hundred metres upstream – they produced an adequate fall of water to drive the wheels whenever power was required. The headwater pool above the mill may have been lined with brick or boards, but the recently exposed foundations to the east of the arch may relate only to a projection shown on 19th century maps. The mill stones may have been placed on the upper storey, in the manner of a post-medieval mill, but could have been suspended at a lower level and fed from above as suggested in figure 1.

Documentary Evidence & Historic Significance

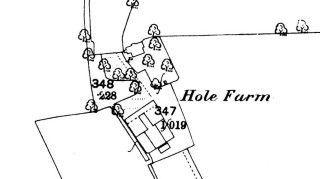

The Waldegrave family gradually lost its wealth and land during the 17th century and finally sold Smallbridge Hall in the early years of the 18th century. By 1680 the Smallbridge estate had been reduced to three adjoining farms, named as Over Hall (1 km to the north-east), Little Mill Farm (now Little Mill Cottage, 750 m to the south) and Russells Farm (Suffolk Record Office ref. 324). Little Mill Cottage is a converted 17th century cart lodge and nothing remains of its farmhouse, but the site lies in the approximate direction of Hold Farm when viewed from Smallbridge and it may derive from Hold Farm’s original name. This is by no means certain, however, as a second medieval mill is known to have existed on the river until the 16th century just 500 m to the west of the same site (known as a curdmill is was used to manufacture cheese). Russell’s Farm was an alternative name for Hold Farm, and a document of 1819, when the estate was bankrupted and sold again, refers to ‘an ancient map of the estate surveyed in 1726 by J. Kendale entitled An actual survey of Small Bridge, Overhall, The Hold Farm and Little Mill’. Unfortunately this map no longer survives. Later 19th century maps label the site as The Hole or Hole Farm, but ‘the Hold Farm’ is probably the older name and may relate to the building’s use as a grain store and mill (cf. a ship’s hold – although ironically this use of the term is thought to derive from ‘hole’). In 1819 Hold Farm contained a modest but respectable 63 acres of land.

Figure 1. Hold Farm on the First Edition Ordnance Survey of 1886 showing a new barn and farm yard and the present truncated outline of the farmhouse. (omitting the large eastern wing of 1988)

The Smallbridge estate was purchased at auction in 1849 by one George Wythes of Reigate, from whom it passed by marriage to the Bristol family of Ickworth. Its three component farms, Over Hall, Hold Farm, and Smallbridge itself (now incorporating Little Mill Farm) were eventually sold separately. A survey prepared for Wythes in 1850 describes the condition of Hold Farm’s buildings and land as ‘most wretched and disgraceful’, and recommends dire consequences for the tenant. Wythes carried out extensive improvements to his new estate, and the Victorian range to the south of the mill probably dates, like many of the hedgerows, from the 1850s. Wythes invested heavily in a new model farm at Smallbridge Hall (among the finest in Britain until its piecemeal destruction in recent years) which included its own watermill powered by diverting the Assington Brook into raised ditches and eventually into an iron chute which delivered water to the wheel.

It is unclear whether the Waldegraves erected their mill on a new site in circa 1520 or rebuilt on older mill. Every manorial lord required his own mill in the early Middle Ages as he could oblige his tenants to use it and benefit accordingly; in consequence the parish of Bures contained at least seven during the 14th century. The main Domesday manor of Tany possessed a ‘winter mill’ in 1339 lying on a stream so small it dried up in summer; Gilbert de Tany’s private chapel of 1218 still stands on the hill above Hold Farm (600 m to the north-west), but his mill probably lay on one of several nearby tributaries of the Assington Brook rather than the brook itself (which flows strongly all year round and powered the main medieval mill in Assington 3.5 km upstream). The manor of Over Hall also possessed a water mill, and a mill at ‘Smalebrug’ is mentioned in a charter of Stoke by Clare priory (which held the church and parsonage manor in Bures) as early as 1090. The bridge over the Assington Brook to the south of Hold Farm may be the small bridge in question, as no bridge capable of spanning the Stour is likely to have been described as small by the standards of the 11th century. The Stoke by Clare Priory cartulary (Suffolk Records Society, 1983) contains a charter of 1090 whereby Gilbert Fitz-Richard donates his income of 20 shillings a year from his mill at “Smalbruge” to the monks of St John at Clare for the lighting of their church. The mill is listed as ‘Smalbreggemell’ on the Priory’s Bures rent rolls between 1382 and 1502 (when its tenant, Sir William Waldegrave, paid 15 shillings for it), but is conspicuous by its absence from the next surviving rental of 1541. The Over Hall mill also disappears from 16th century records, having appeared separately in 15th century inventories and a comprehensive survey of Waldegrave manors taken in 1577 records only the two Stour mills at Nether Hall and Wormingford.

The mill at Hold Farm mill comfortably fits these date parameters and it seems clear that between 1502 and 1541 the Waldegraves rebuilt the ancient Smallbridge mill to serve as the demesne watermill for their substantial local estates, either on its original site or that of the Over Hall mill. It was designed as a showpiece by one of the wealthiest families in the land. To my knowledge it survives as the earliest secular mill in the country, and one of a handful to illustrate the nature of medieval mills before the advent of multiple gearing in the 17th century. As such its historic importance is difficult to exaggerate, and any future groundworks or alterations to the fabric should be carefully monitored. The present listing at grade II, which fails to recognise Hold Farm’s true form and significance (it wrongly describes the front elevation as jettied, for example) should be increased to grade II* or grade I (as at Abbotsbury and Fountains Abbey), and any repeat of the substantial losses to the original fabric which occurred in 1988 should be avoided.

Illus 8. Hold Farm from the south-west, showing its proximity to the Assington Brook, seen here in flood.

Drawing Convention

The drawings accompanying this report seek to record the features of the original building, and do not necessarily include later alterations. Broken lines indicate timbers or walls for which evidence exists but that are either concealed or missing, although some features are reconstructed from photographs taken in 1988. All exposed joint pegs are shown, and scales are in feet.

Leigh Alston

Leigh Alston is a building archaeologist and medieval historian who specialises in the recording and analysis of timber-framed structures. He lectures in the Department of Archaeology at Cambridge University but also undertakes commissions on a freelance basis for English Heritage, the National Trust and various county archaeological units. Recent publications include ‘Late Medieval Workshops in East Anglia’ in ‘The Vernacular Workshop’ edited by Paul Barnwell & Malcolm Airs (Council for British Archaeology and English Heritage, 2004) and the National Trust guidebook to Lavenham Guildhall (National Trust 2004).