A Castle Reborn

Hedingham Castle, Essex, part II

The home of Jason and Demetra Lindsay

In the second of two articles, John Goodall considers how a great medieval castle became a Georgian country seat and reports on an exemplary restoration project. Photographs by Paul Highnam.

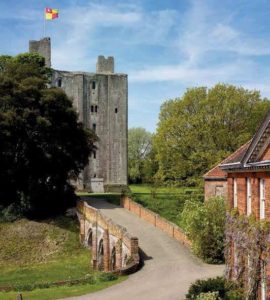

Fig 1: The new house stands within the outer bailey of the castle. It is connected to the inner bailey with its great tower of the 1140s by a fine Tudor bridge built of brick.

On March 22, 1703, the body of Aubrey de Vere, 20th Earl of Oxford, was laid to rest in Westminster Abbey. With him was extinguished a title that had descended, along with the hereditary office of Lord Chamberlain, directly in the male line since 1142. Impressive though the Earl’s pedigree undoubtedly was, however, its accompanying patrimony had been sadly reduced since the Middle Ages. As an emblem of this decline, the ancient seat of the family at Hedingham Castle had been largely demolished and finally alienated in 1655.

Ten years after the last Earl’s death, however, this ruinous castle was unexpectedly brought to life again with new money from London. In 1713, Lord and Lady Cullen, to whom the property had descended through the Trentham family, sold the Hedingham Castle estate to one Robert Ashhurst. He was the third son of Sir William Ashhurst, a Lancastrian Nonconformist who became both an MP and Lord Mayor of London before his death at the age of 73 in 1720. Confusingly, many authorities incorrectly describe Sir William as the purchaser of the property.

In acquiring Hedingham Castle, Robert almost certainly aimed to dignify a successful mercantile career in time-honoured fashion by becoming a country squire. At the time of the purchase, he was already in his early forties and had been married for nearly 20 years (although he would be widowed and marry again before his own death in 1725). His social circle was formed both by his City connections and his Nonconformist roots.

One close member of his wider family circle was the intriguing Mary, Lady Abney. She was the daughter of a Presbyterian merchant, the wife of a noted Nonconformist Lord Mayor and, as a widow, a significant benefactor of Nonconformity in her own right. Her chaplain was the independent minister and hymn-writer Isaac Watts and she became a guardian of Robert’s daughters.

No documentary evidence survives to record Robert’s changes to Hedingham, but the likelihood is that he immediately set to work planning and then constructing a new house on the site of the medieval castle. This comprised two ditched enclosures or baileys on a figure-of-eight plan that were connected by a Tudor brick bridge. It is possible that a small residence had been pieced together from the castle ruins in the 17th century, but, if so, nothing obvious remains from it. The sole important medieval survival was the huge Romanesque tower in the inner bailey. In 1713, it must have been the tallest building in the county. The new house was laid out directly adjacent to it in the former outer bailey at the bottom of the Tudor bridge (Fig 1).

Fig 2: The seven-bay south front of the house. To the left is visible the pedimented service range.

Its main block was a brick box two storeys high above a basement, seven window bays broad (Fig 2) and five deep. The parapets of the building were ornamented with a balustrade, but the only other external ornament was a restrained door-case in the centre of the main, south-facing front and another to the west.

A series of lead waterheads bear the date 1719, which suggests that the building was being completed that year. An octagonal dovecote a short distance from the house, which was recently restored with the financial support of the Country Houses Foundation, also has the date 1720 picked out in blackened bricks.

Connected corner to corner to the main house by a rusticated archway was a two-storey service and kitchen wing with a low pediment. This screened a stable court to the rear (north). In front of the house, to the south, the outer-bailey earthworks were levelled away to create a landscape view away from the adjacent village. Two small gazebos were erected and the keep itself, which was evidently a ruined shell, was perhaps turned into a garden building with new floors and a roof. Behind the house, the inner bailey earthworks were reshaped to form garden terraces.

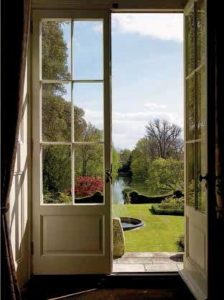

Fig 7: The view from what was originally the front door southwards down the canal.

These changes created a fine view of the house from the south that is repeatedly captured in 18th-century views. They show, from left to right, the keep, the Tudor bridge, a small ornamental obelisk in the stable yard, the kitchen range and the house itself. Work to the grounds was still under way when Robert died in 1725 and, the following year, his eldest son, William, signed an agreement with a gardener, Adam Holt of Leytonstone, to lay out new lawns, walks and an avenue.

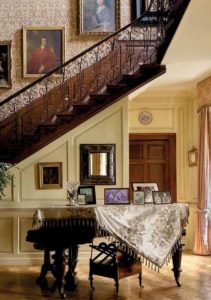

Holt also formalised the arrangement of medieval pools to the south of the house as a canal on the axis of the front door with an octagonal basin at one end (Fig 7). Meanwhile, William’s accounts record the payment of £80 3s to one William Harrison in November 1726 for the ‘iron gates and rails at Henningham Castle’. This is certainly a reference to the handsome ironwork that formerly enclosed a small forecourt. Might this be the same man who produced the splendid staircase in the principal hall ? (Fig 3) In the same year, he also paid William Cooper £44 9s ‘for the monument and stone cutters work at Henningham Castle’, presumably for the memorial to his father in the parish church.

Fig 3: The staircase hall with its splendid ironwork balustrade. The position of the staircase in the central front room is unusual.

After William’s death in 1735, the estate passed to his younger brother, Thomas, who made further minor changes to the interiors. According to his ‘Country House’ account for May 1747, he paid William Curtis for surveying (‘Sirvaing’ in the orginal) the house. The ensuing changes included the creation of ‘an arch in the drawing room’ (Fig 5), the enlargement of windows in the parlour and the installation of a marble chimneypiece purchased from Richard Fortman. At a cost of £12 12s, this last fitting was expensive, but not opulent. The following year, in July 1748, Horace Walpole visited the castle, ‘the last remains of the glory of the old Aubrey de Veres, Earls of Oxford… shrunk to one vast ruinous tower, that stands on a spacious mount raised on a high hill with a large fosse’. He was not impressed, however, by the modern additions, snidely remarking that the castle ‘belongs to Mr Ashurst a rich citizen who has built a trumpery new house close to it’.

Fig 5: The drawing-room fireplace incorporates a painted overmantel.

Curiously, in the 1750s, he collected a cupola or lantern for the staircase of his own celebrated Gothic house at Strawberry Hill that supposedly came from the castle ruins. When Thomas died without heirs in 1765, the estate reverted back to his elder brother’s line. William’s sister, Elizabeth, had married Sir Henry Hoghton and died giving birth to her only child in 1761, another Elizabeth. Sir Henry, therefore, took control of the estate and was possibly the figure who began to soften its formal landscape setting. Certainly, an estate map of 1766 by G. Sangster shows that the forecourt of the house had now been replaced by a turning circle for carriages.

In 1777, Sir Henry tried to sell Hedingham Castle, but, six years later, he conveyed it to his daughter and her husband from 1783, Lewis Majendie. The Majendie family was of Hugenot descent and formidably well connected. Lewis himself was a figure with impressively wide interests. As well as serving as a soldier, he was a founder member of the Linnean Society and a Fellow of both the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. He continued the transformation of the castle grounds with extensive new plantations of trees and also—as we saw last week— commissioned a remarkable architectural survey of the keep, which was published in 1794.

Upon his death in 1833, the castle passed to his eldest son, Ashurst Majendie. His heir in 1867 was a nephew, Lewis Ashurst Majendie, another figure with strong antiquarian interests. The year after he inherited, he oversaw the archaeological excavation of the inner bailey.

Fig 8: The 1870s dining room fireplace incorporates Tudor panelling.

As it appears today, the house is very much the creation of this second Lewis and his wife, Lady Margaret, a daughter of the 25th Earl of Crawford and Balcarres. It was probably shortly after their wedding in 1870 (and certainly by 1876) that they effected a major overhaul of the building. They erected a porch over the archway connecting the service range with the main building and completely reconfigured several of the interiors with well-chosen period fittings.

To them, for example, can be attributed the impressive dining room in the service range (Fig 8) as well as the fine glazed fireplace in the former boudoir (Fig 4). It’s likely too that the fine hall fireplace is a piece of period salvage introduced in the 1870s (Fig 6). Whatever the case, the house was effectively in its modern form by 1896 when this ‘charming family mansion’ was offered for auction on August 13 in London. For some reason, the house was not sold, but was leased out for a period.

Fig 4: The present kitchen furnished as a boudoir in the 1870s with this glazed fireplace.

Fig 6: The fireplace in the hall may be an insertion of the 1870s.

It was back in family occupation, however, when its interiors and furnishings were photographed by COUNTRY LIFE for an article published on September 18, 1920. In 1939, the estate was unexpectedly inherited by Musette Majendie, who lived here for the rest of her life. The house subsequently escaped requisitioning during the Second World War, but, in the 1950s, Miss Majendie leased a large number of rooms to elderly residents to supplement her income. This institutional use came to an end at her death in 1981. She left Hedingham Castle—now shorn of most of its estate—to her cousin, The Hon Thomas Lindsay.

By happy coincidence, he could trace his descent from the de Veres through both his father’s and mother’s families. In this sense, the bequest reunited Hedingham Castle with its founding family after a 300-year interlude. With his wife, Virginia, he decided to open the castle and keep to the public, but the neighbouring house stood largely empty.

Jason Lindsay, the present owner and one of their sons, was introduced to the problems of managing Hedingham Castle by his parents. After his marriage to Demetra, an architect, the couple decided to move into the house and develop the whole site further. Theirs has been a very hands-on approach, which has greatly benefited from careful planning and enthusiasm. It has also cumulatively transformed the property in an exciting and exemplary fashion.

They moved into the empty house 12 years ago, just before the birth of their eldest daughter. Since then, they have gradually returned the whole to life as a family home. Their particular contributions to the interior have been the creation of a stylish kitchen in the former boudoir and the restoration of the former dining room. When the installation costs for the hung silk in this latter room far exceeded their purse, they simply got on with the job themselves.

Between October 2008 and August 2009, they took part in a garden restoration television programme commissioned by Channel 4 called The Landscape Man and used the publicity as a means to unlocking sponsorship. During the course of the filming, they were able to make major changes to the landscape, restoring the 1890s bog garden and clearing the 18th-century canal and octagonal pool.

At the same time, they embarked on the renovation of the keep as a wedding venue, with impressive results. In this building, the public can see one of the outstanding survivals of Romanesque architecture in the country thriving in private care and without State support. Perhaps against the odds, the Lindsays have decisively put Hedingham Castle back on its feet once more. Theirs is a tremendous achievement.

Hedingham Castle is in the very middle of the area covered by the CSCA. If you do not know it, it is well worth a visit and is a very special place for a wedding.