ALSTON COURT

Alston Court forms the southern side of the former market place in the centre of Nayland, close to St James’ church. Its modest exterior and high-walled garden conceal one of the most important and spectacular medieval merchants’ houses in Britain. I first saw the place as a budding architectural historian in about 1990 (architectural historians notoriously blossom late in life), and was struck by the coincidence of names: surely it had to be my ancestral seat. Sadly I discovered any connection I might have with the eponymous family of solicitors which owned the house for two centuries was sufficiently distant to render any legal claim highly tenuous. As I couldn’t afford the central heating bill let alone the asking price I decided instead to unravel its many secrets for the benefit of posterity.

Listed at grade I the house dates in part from the 13th century and preserves an impressive 15th century open hall along with some exquisite carving and possibly the finest collection of early-16th century heraldic stained glass in Britain. The fully enclosed rear courtyard is completely hidden from the street and forms a time capsule, almost unchanged since the Tudor period, complete with a picturesque array of oriel windows and brick nogging between its exposed timbers. These windows survived as they were blocked with plaster and converted into cupboards, perhaps in response to the window tax of 1696, before being re-opened in 1902 as part of a major Edwardian restoration.

1. Alston Court from Nayland’s medieval Market Place. The anonymous right-hand wing dates from the 13th century and may be the oldest two- storied timber-framed and jettied structure in Britain.

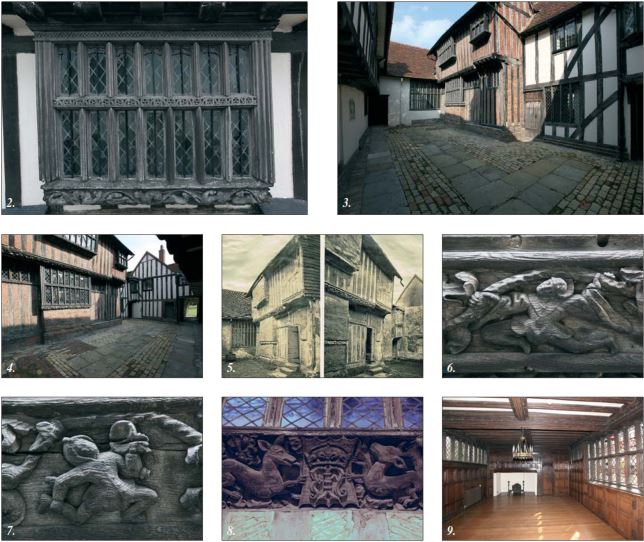

2. The fine early-16th century oriel window of the left-hand parlour cross- wing, complete with original tracery and carved animals. Similar windows were probably added to the rest of the 15th century facade as part of a Tudor upgrade, and this example survives only because it was bricked over for centuries and re-discovered in 1903.

3. The inner courtyard looking north towards the 15th century open hall with the brick-nogged early-16th century rear parlour and solar in the centre. The stair turret to its right was heavily restored in 1903.

4. The courtyard looking south.

5. Photographs of the courtyard before 1903 when the Tudor windows were still covered with lath-and-plaster (kindly provided by Alston family historian Edward Liveing Fenn of New Zealand, whose grandfather restored the house).

6. One of the Renaissance-style figures carved on the jetty bressumer of the rear parlour.

7. Another figure on the jetty bressumer, wearing a close-fitting hooded tunic with what appear to be tassels on his elbows and hood. Is he dancing, or playing a game with a dished bat?

8. The fine shield on the window sill of the solar. Its shape is identical to the internal shield but carries a well known Marian device (i.e. a cipher combining all five letters of MARIA).

9. The rear parlour (now the dining room) with its largely complete early- 17th century panelling and carved ceiling. This was a kitchen in the 19th century and the oriel window formed a cupboard containing three shelves.

10. A carved ‘halberdier’ in the rear parlour. This figure retains traces of paint that may be original.

11. Some of the rare early-16th century heraldic glass in the dining room. The arms to the left are labelled Payn but had been adopted by the Abell family before 1573. This glass was moved to the dining room in 1903 from the solar and another first-floor room in the western wing.

12. The early-15th century open hall. Evidence of a 13th century open hearth was found a metre below the present floor during excavations of 2003. The lighter timber is Edwardian but the carved crown-post in the roof is original and still encrusted with medieval soot.

13. The early-16th century solar above the rear parlour. The carved ceiling here is almost entirely original and among the finest of its period in the country. The iron tie-beam was inserted in the 19th century to prevent the walls from spreading but was removed in the 1920s – before being rapidly reinstated.

14. One of the two false hammer beams in the solar, carved as bearded ‘prophets’. The shield beneath is of the same date as the oriel window but hides mortises for a missing post and both it and the window represents early alterations or a change of plan during construction. The crowned A is a medieval cipher for Amor Vincit Omnia, as recorded by Chaucer, but the Tudors loved a good pun and it may also represent Abell, Anne Abell and Katherine of Aragon. Not to mention that fine old Anglo-Saxon surname: Alston.

15. The bearded prophet on the eastern side of the solar.

16. The central boss of the solar, profusely carved with pomegranates.

17. A detail of a figure holding a goose carved on a bracket in the solar ceiling.

18. A unicorn in the solar, as fresh and sharp as the day it was carved in the early-16th century.

19. Another beast carved on a bracket of the solar’s vaulted ceiling.

20. Two beasts in the solar, one with his tongue lolling out. Traces of old limewash can be seen between his teeth.

The original building faced the market place to the north and reflected the usual medieval domestic layout with a central barn-like open hall, heated by a bonfire burning on its clay floor, flanked by service (i.e. storage) rooms to the right and a parlour to the left. The right-hand cross- wing is the least decorated part of the house but is probably the oldest and most complete two-storied timber-framed and jettied structure in the country. Its wall timbers are widely spaced, in contrast to the ‘close- studding’ that became fashionable later in the Middle Ages, but it contains archaic carpentry features such as notched-lap joints, passing braces and splayed scarf joints usually associated with 13th century halls and barns that were aisled like churches. The roof design is strikingly similar to that of nearby Abbas Hall in Great Cornard for which the timbers were felled in 1289. The scar of a low-walled but very wide aisled hall can still be seen internally, along with the arched recess of a service door, but the present hall and parlour cross-wing were rebuilt on the same site in circa 1420. The older wing appears to have been given a matching new facade at the same, but this is now plastered externally.

At the beginning of the 16th century a new rear parlour and first floor ‘solar’ with carved decoration of the very best quality was inserted into the middle of the 15th century parlour wing, leaving the latter’s rear bay intact. A large but plainly-built new range was added to the rear of the 13th century wing at approximately the same time; this contained a single, undivided chamber on its upper storey with three rooms below that were entered from the courtyard. The central room appears to have been designed as a commercial dye-house as cloth manufacturing was the only source of significant wealth in Tudor Nayland and its ceiling contained a large aperture to accommodate an open furnace with smoke-blackened rafters and evidence of a louver above. The southern room of this wing overlapped what appears to have been the northern parlour of an entirely separate late-15th century property that was jettied towards the church on the east. A small additional early-16th century structure, jettied to front and rear, was built to link the corner of this formerly separate property with the 15th century parlour wing, thereby enclosing the courtyard.

The ownership of the building is unfortunately uncertain until it was named as ‘Grooms’ in the 1606 will of Andrew Parish, a Nayland clothier. It retained this name until the Edwardian restoration, when it was rechristened in honour of the Alston family of lawyers who acquired it in 1768, and remained in effective possession until 1968. The earlier name probably derives from the family of William Groom of Nayland, who left a will in 1475. Research into the builder of the fine rear parlour and solar, points towards two of the wealthiest clothiers in Nayland during the 1520s: John Payn and John Abell who died in 1526 and1523 respectively. The stained glass illustrates the connections of the Payn family which originated in Norfolk, but by 1573 the Payn Arms had been adopted by the Abell family, suggesting a marriage between the two. The Abells were far wealthier than the Payns, with extensive lands and manors across the region, and are more likely to have been responsible for the new work which is far above the usual standard of even the richest local merchants. John Abell’s eldest son, Thomas, became chaplain to Henry VIII’s queen Katharine of Aragon in the 1520s, publishing a book in her cause and spending several years in the Tower for his trouble – before being hung, drawn and quartered in 1540. Could Thomas have had a hand in the new work at Alston Court? The carved ceiling and jetty beams are certainly smothered in pomegranates – Katherine’s famous symbol – and the letter A carved on an original shield in the solar could be read as a multiple pun: a crowned A is a well- known medieval device for Amor Vincit Omnia (love conquers everything), worn as a badge by Chaucer’s Prioress, but it could also represent Abell, Aragon, and Anne Abell the young widow of John Abell. Every good house should retain a few unanswered questions.

Leigh Alston

Leigh Alston is an expert in old buildings, as was evident from his article last year, on Hold Farm. If you live in an old building and want to know more about it, why not contact him? He lives in Bures.