By Canoe to Cattawade

The 2004 edition of this newsletter carried an account of a journey to the source of the Stour. This time we decided to head towards the sea and explore the delights of the “Navigation”.

The River Stour Navigation, which was established by act of parliament in 1705, covers the river from Sudbury to Cattawade, and is now the responsibility of the Environment Agency. Owing to the decline of commercial activity over the last century or so, most of the locks and tow paths have disappeared and modern navigators, like Zambezi explorers before them, are thrown back on the canoe. Before plunging in (so to speak), we felt it a good idea to apprise ourselves of the awful dangers said by the Environment Agency to await us. “It is good practice” says the EA “to paddle in a group of at least 3 boats, one to stay with any casualty and one to seek assistance. Do not swallow river water”, it advises, “avoid unnecessary immersion; where possible shower after contact with river water; watch out for leptospirosis, Weil’s disease, and hepatitis A”. In the face of such dire warnings it is scarcely a surprise that the majority of citizens vote to stay at home slumped in front of the telly.

10 o’clock on a brilliant June morning found us on a slipway behind the Quay theatre in Sudbury conversing with a family of ducks. Behind us, a borrowed Canadian canoe contained our lunch and other necessities for the voyage.

Once afloat and after a little practical instruction on how to handle the paddles, we found ourselves almost instantly in a magical enclosed world of waterlilies, dragonflies, damselflies, cricket-bat willows, swans, and stinging nettles. Just above the water fluttered a thousand banded demoiselles dancing and shimmering in the heat. The demoiselle is as seductive as its name suggests; the male is metallic blue and the female shiny green. The male has a dark blue patch on his wings which somehow gives the illusion that there is more than one of him. To attract the female he flutters alluringly in front of her while at the same time dozens of unattached males try to get in on the act. The whole river pulsated with excitement.

The first obstacle to overcome was the weir at Cornard which, because the river was rather low, looked more like a slimy water slide. The River Stour Trust has, at great expense, rebuilt the lock, but it is largely unused and sits there empty and a bit forlorn. It can allegedly be used by prior arrangement with the trust. Our personal trainer and canoeing instructor, who had accompanied us in a kayak, shot down the weir with scarcely a second thought. We felt that at such an early stage in our canoeing careers, discretion was the order of the day. It was time for our first bit of portaging.The word portage sounds like a noun, but is used also as a rather awkward verb, thus proving, if that were necessary in this ungrammatical world, that there’s no noun that can’t be verbed. We duly dragged the canoe round the weir.

Just below the lock is the site of the old Nestle factory on which have recently been built some flats that might belong properly in Gotham City. They are tall and pointed and built right on the edge of the river where they can best be flooded. In anticipation of such an event, the bottom storey is seemingly kept empty, perhaps to house rescue craft. Next door to the flats, a housing estate of prize-winning mediocrity has recently sprung up. The houses stare blankly at the river, their features unrelieved by any pretence at architectural detail. One can but hope that they will be washed away in quick order. The only positive aspect of this latest blot on the Stour landscape is that, by comparison, the flats look positively handsome.

The weir at Henny is adjacent to the Swan pub, once the haunt of bargemen, now fancied up and suffering from regular changes of ownership. It was still before 11a.m. and trade was far from brisk. We portaged round the weir, feeling rather cowardly, while our trainer shot down in Olympian style. We sat for a few minutes on Sharpfight Meadow, the far side of the river from the Swan, where Boadicea (now less harmoniously called Boudica) is said to have caught up with a Roman legion and slaughtered them. This is dragon country and legend has it that Henny had two of them, one black and the other red with spots. They fought each other and the spotted one won. Disliking the publicity they both retired to the hills.

The next obstruction was the Henny Regulator Weir. This is a far from imposing structure being no more than a concrete beam across the river about 2 inches above water level. Applying maximum muscle power we sped towards it, paddles bending under the strain, and came to a juddering halt balanced neatly astride the beam. It took a good deal of tugging and manic thrashing around to get us off. Looking at the map, (after the event of course), it says “Caution. This structure may be submerged and craft can easily become caught.”

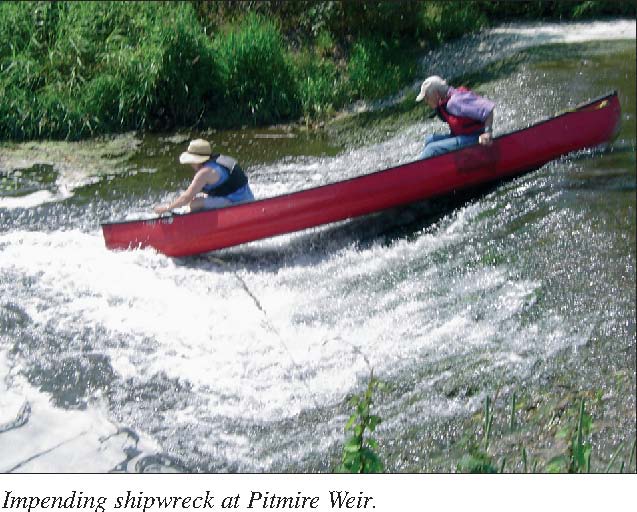

Shortly after we entered the Daws Hall wildlife reserve, which feels gloriously jungly and where several thousand children each year get the chance to study native fauna and flora. Pitmire weir is within the reserve and, having arrived there, we did a recce to see how best to tackle it.

The verdict, having peered over the edge, was that there was plenty of water for a soft landing if we shot the weir, and this we did. In the event, the canoe descended at a 45 degree angle and, instead of the bow rising heroically when it hit the water at the bottom, there was a nasty crunch. The canoe, by then more or less upright, slowly turned over and the occupants were precipitated into the stream. Luckily the weather was warm and the water shallow. We emptied the canoe and had lunch.

Lamarsh weir, the last obstruction before Bures, is a cinch. It has a channel in the top, described as a fish pass, and, greenhorns though we were, we shot through unscathed. Exhausted by our efforts, the final stretch to Bures recreation ground was a hard slog, partly because it was so difficult at river level to tell where we were. Tantalising glimpses of the Sudbury road were invariably misleading as yet another bend unravelled itself. But at last landfall was made at the millennium bridge in Bures where the local youth, oblivious of Weil’s disease, were dangling each other above the water. We made for home.

The second stage of our voyage took place on another glorious day a month later. This time we had borrowed a four man canoe of stout construction complete with a weighty picnic, wheels for the portaging and two further carefully selected oarspersons, whom we frightened a good deal with highly embellished descriptions of the shipwreck at Pitmire weir.

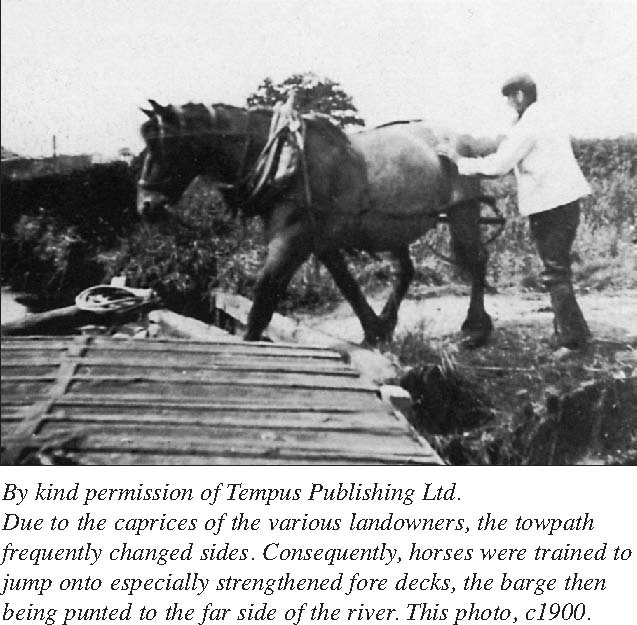

On a summer’s day the stretch from Bures to Boxted Mill has a positively voluptuous feel about it. There is little sign now of the river’s commercial past. The magnificent mill buildings at Bures, Wiston and Boxted have been converted into private houses; tow-paths and locks have disappeared; and the river, which was canalised between 1705 and 1713, is frequently overgrown with reeds. River traffic reached its peak in Constable’s time and, as a fully laden barge had a draft of 3 feet, there must have been a constant need for dredging. Because there was no continuous tow path on either bank, the barge horses had to cross the river 33 times between Cattawade and Sudbury. If there was no bridge, and there were only 16 of them, the horse had to be ferried across on the barge. The river has now reverted to pre-barging days.

We started at the Bures millennium bridge from which it is a short paddle to Bures Mill, where it is necessary to portage round the weir. Until very recently, the portage was celebrated for the fact that the canoe had to be dragged under a bridge so low that the portagers had to more or less lie flat on their stomachs. (Gryff Rhys-Jones recently carried out this feat with much groaning for the benefit of television viewers). The EA have now built a new bridge with miles of clearance, but under it is a deep and precipitous ditch along which to manoeuvre. As the ditch had about 8 inches of water in it, we emerged on the very fine mill pond rather wet and muddy.

From this point on, the canoe was frequently hemmed in by massive clumps of reeds and rushes, requiring the pilot to make snap decisions on whether to go left or right, or how to get out of the impasse if the helmsman at the back showed symptoms of dyslexia or otherwise failed to carry out instructions. We zig-zagged somewhat chaotically until we sighted another canoe coming in our direction, paddled, most elegantly, by the Lady of Shalot. She offered us coffee and a look at the test match, neither of which we were able to resist. We felt a bit fraudulent having only come about a mile, but Australia were 300ish for 5 and Flintoff had just come on to bowl; so we lingered. A famous victory was in the air.

Invisible from the river on the Essex side as one approaches Wormingford, is the mysterious Wormingford Mere where lurks yet another dragon. It is recorded that in the year 1405 “close to the town of Bures, near Sudbury, there has lately appeared, to the great hurt of the countryside, a dragon, vast in body, with a crested head, teeth like a saw, and a tail extending to an enormous length. Having slaughtered the shepherd of a flock, it devoured many sheep. There came forth an order, to shoot at him with arrows, but the dragon’s body although struck by the archers, remained unhurt, for those arrows bounced off his back if it were (sic) been iron or hard rock. In order to destroy him, all the country people round were summoned, When the dragon saw that he was again to be assailed with arrows, he fled into Wormingford Mere.”

Looking towards Wormingford bridge from the portage round the weir is the finest view on the whole river. John Nash often painted and fished here. We decanted from the canoe, hauled it out of the water and there found the proprietors making the most of their view and with drinks at the ready. Much invigorated, we set off again past the manicured lawns of the mill house and under the bridge in the direction of Wiston.

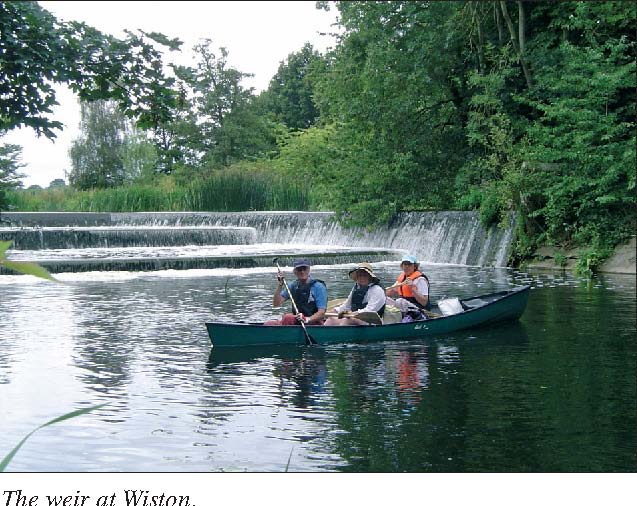

The valley between Wormingford and Wiston rises steeply on the Suffolk side towards Leavenheath and then Stoke-by-Nayland, whose church tower dominates the surrounding countryside. There is a wonderful view of the river and its water meadows looking down from the Bures to Nayland road, and this is the stretch on which we now found ourselves. The river here is at its most luscious, tranquil and romantic. There is inevitably a caravan site, but it is still a glorious stretch of river. The mill house at Wiston presides over another beautiful mill pond and horseshoe weir. Willows, white weather-boarding, rushing water – it’s perfection, but also private and we sped on. After a few yards we grounded.

Arriving in Nayland, a tunnel takes you under the A134 then along the back of the tudor houses in Bear street to a weir which is very similar to that at Wiston, though the surroundings are less decorative. There was a short length of tow path where we lowered the boat back into the river and, as we did so, a man with a beard passed by – the only pedestrian we saw that day. “You’re very brave”, he said – “or very stupid.” Right on both counts, I thought. He walked on and then stood looking down at us from Abell’s bridge in front of the Anchor Inn, waiting for us to capsize. The bridge is decorated with a stone plaque bearing a rebus, a bell surmounted by the letter A.

Eschewing the delights of the Anchor, we hurried on to the bridge beyond the pub’s huge vegetable garden. Under the bridge, the weeds, reeds etc had been cut and formed an impenetrable layer on top of the water. It was like paddling through setting cement but more difficult. My resolve was stiffened by thinking of Sir Samuel Baker and his indomitable wife (whom he had carried off a few years previously from a slave market in Hungary) battling through the Sudd, on their way up the Nile. We eventually dug our way through, but it took an eternity to cover about 50 yards.

The portage at Boxted Mill is lengthy and through a private garden. We held our breath, walked on tiptoe and hoped the gardener wouldn’t shoot us. Luckily he was the other side of the mill pond and, though he put the evil eye on us, we didn’t sink. The reeds then enveloped us again. Shortly after, we were diverted by what appeared to be a massive bug zipping around on the surface of the water but which on closer inspection turned out to be the head of a water snake.

Langham is a disappointment. Sir Alfred Munnings once wrote “To use the word Arcadia here is not affectation. No other word could describe Langham mill, its lock, bridge, mill-pool, flood-gates and trees”. The mill has entirely disappeared, replaced by a massive waterworks. The exotically named Langham Flumes precede the waterworks and provide a little bit of white water for serious canoeing enthusiasts, but with our heavy boat we portaged round.

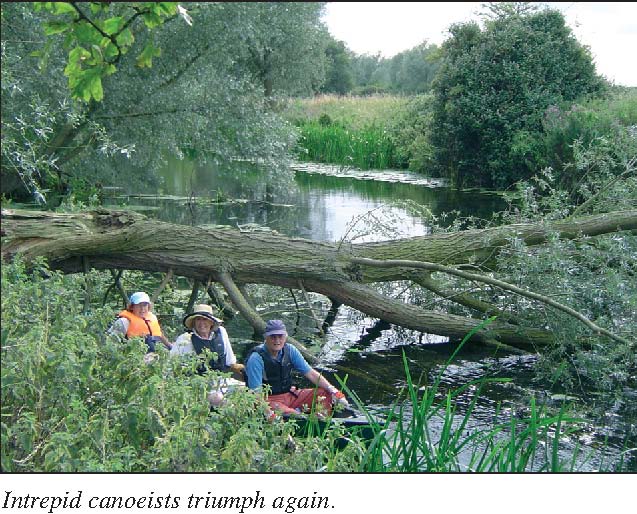

Higham church then came into view, and it seemed shortly after that the expedition might have to be aborted as progress was blocked by a huge willow which had fallen across the river.

After much investigation, we were able to force our way through and so on to Stratford St. Mary where, instead of taking the left-hand stream which would have led us to the

portage belonging to the Swan Inn, we took the cut on the right and got into all sorts of difficulties. The stream ended in a difficult portage below which there was almost no water, as the River Stour Trust was rebuilding the lock and had dammed the stream. There being no way of disembarking and getting into the village, I walked along the side of the weir to the road to find out where we were, and on my return found that the rest of the crew, grown rebellious, were below the portage and heading seawards. Since the next portage was Dedham and it was after 6 o’clock, we had to haul the canoe back up whence we had come. This time we took the right turn and, somewhat the worse for wear, met up with our lift back to Bures.

A fine August morning a month later found us back at the Swan in Stratford St Mary. The proprietor allowed us to launch the canoe from the pub’s landing stage and in no time we were back at the portage where we had so incompetently thrashed around a month before. Volunteers were cheerfully rebuilding the cut running up to the lock, putting hay on the mud to prevent it squirting up and covering them. Below the portage there was, this time, plenty of water and the river then runs broad and wide down to the Talbooth and the A12 bridge. The old road bridge is a hideous concrete affair; the new bridge alongside it rather elegant by comparison. The unfortunate and very picturesque Talbooth, however, is now dominated by the roar of traffic on the A12 – a sorry fate.

Constable would find the next stretch down to the lock at Dedham pretty much unchanged. Stratford St. Mary church stands on the left with a foreground of cows, and to starboard is the knapped flint tower of St. Mary the Virgin Dedham. A kingfisher shot ahead of us as we drew parallel with a miniature classical temple perched right on the water’s edge. It is in fact a boathouse built in 1939 by the architect Raymond Erith for his aunt Maud.

Ionic boathouse at Dedham. “Health & Safety” at work!

A few hundred yards further on, the way is blocked by Clovers Mill, large, Victorian, red brick and now turned into flats. It is the successor to the mill worked by John Constable’s father. Alongside is a weir and a lock, restored but deserted. The portage was the most challenging yet. We dragged the canoe across a meadow and sat on it for a coffee break before expending our remaining energies relaunching below the lock and more or less opposite the boathouse restaurant. Here the river is suddenly overrun with rowing boats, somewhat erratically handled by enthusiastic but incompetent oarspersons. With all of 21/2 days experience under our belts, we looked at them pityingly.

Rain threatened and we tied up to an ancient pollarded willow under which we had our lunch, while swans tried to steal our sandwiches. By the time we got to Flatford, the boats had thinned out and it was drizzling. The famous mill, now a field study centre, looked even better than the pictures, as did the romantic view of Willy Lott’s cottage. But the portage was even more demanding than the one at Dedham and well nigh finished us off. Luckily, most of the tourists had been driven away by the rain and were not on hand to jeer. Once afloat, we did a victorious tour of the mill pond just to shew the remaining onlookers that we were battle-hardened sailors, and headed off along a stretch of well manicured river in the direction of the Judas Gap. At the gap, which sounds as if it was named by Quentin Blake but probably wasn’t, there is a weir which prevents the sea flowing up to Flatford. We were forced to do an abrupt left turn ahead of it and immediately found ourselves floundering in a morass of blanket weed. It was back to the Sudd. We were getting a trifle dispirited, when the stream narrowed, cleared, and with one final heave we were free. Brantham Old Tidal Stop Lock presented no impediment. We glided through and from then on it was all sky and reeds, feeling ever more estuarial until Cattawade came into view.

Before we knew where we were, we found we had arrived at the picnic site provided by Suffolk County Council where we were due to meet our lift home. There being no sign of the lift, we went through the tunnel under the road bridge and on to the barrage itself where we disembarked and climbed up to get a view of the sea. There was none

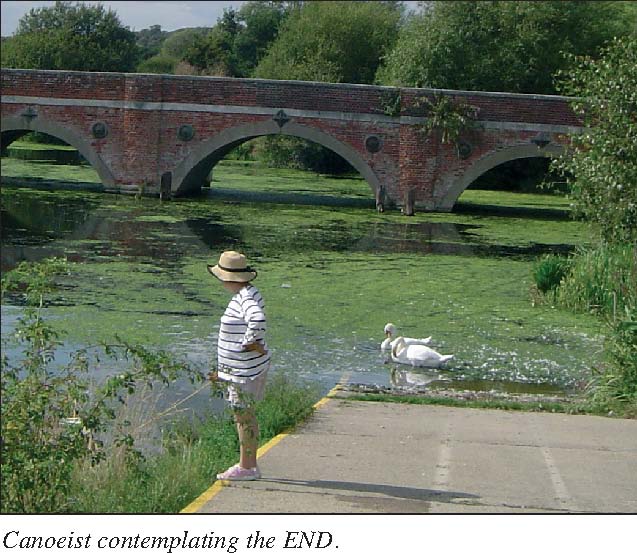

– just a lot more riverish water stretching to the horizon. Behind us, looking upstream, was the rather fine old red-brick Cattawade bridge. We paddled back through it, hauled the canoe onto dry land and awaited rescue.

Jeremy Hill

Once again, Jeremy has come up trumps. His articles are always enjoyable to read and I hope that he can be persuaded to keep writing.