By Hook or by Crook

Not a million miles away lie the two villages of Maplestead. When William the Conqueror invaded England ‘Mapulderstede’ was recorded as one settlement. Two centuries later it was split up. The name is derived from the Anglo-Saxon ‘ a place where maples grew’. The name, variously spelt, was also acquired by those who moved away denoting whence they came. These written references surely emphasised the importance of those Essex maples. But then a millennium later, with momentum in landscape painting gathering pace, it became the turn of artists to record trees.

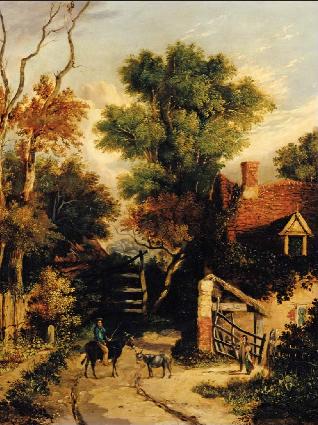

Field maples, once used for their hard timber, still thrive in East Anglia and yet often remain rather elusive, hidden in hedgerows. Today we see woods and trees as part of a picturesque landscape, but two centuries ago they were a vital commodity and often represented a landowner’s ‘bank’ balance. It was at this time that the Norwich School evolved under John Crome and Robert Ladbrooke. Through it, and through Gainsborough’s and Constable’s eyes, we can now look back on observations of historical interest. The painting by Ladbrooke’s son, John Berney, (fig 1), shows a roadside maple, dead centre, in full reddish autumn foliage, so ‘terracotta’ in fact that it matches the pantiles of the cottage. Yet, not untypically, the maple is shadowed and shrouded by an ash yet to turn colour. Those colours are true and timely, for the painter has chosen to render the changing countryside on a bright and sunny autumn morning. If it were not for the quaint children and the cart-rutted road it could be a fading glimpse of deep Essex even today.

Fig. 1, Autumn arriving, terracotta maple (centre), by John Berney Ladbrooke, c 1830

The Norwich Society of Artists was formed in 1803. Crome began working life, aged twelve, as an errant errand boy for Dr Rigby, an eminent physician, but overdid his devilish pranks by swapping labels around on medicine bottles. He was next apprenticed to a sign writer but was taken aback one day when asked to paint ‘The Shoulder of Mutton’. Crome acquired a joint from a butcher and shortly presented the new sign to the innkeeper. Horrified, the publican stated he wanted it roasted, not pearly white. Later, whilst engaged in painting small landscapes in the 1790s in a hired garret, to help earn a crust or two, Crome’s work came to the attention of a wealthy Mr Harvey. Invited to his house Crome was introduced to works of Cuyp, Hobbema and Gainsborough. This was all that was required to inspire the young artist. Managing, now, to sell more paintings Crome had no further need to chase the landlord’s cat, to snip new brushes from its tail!

Artists first devoted their attention to locations around their ancient city. In rolling country of valleys, woods, and meadows, much resting upon sand and flint from the Ice Age, the painted lanes took on rich golden hues peopled as they were by travellers, drovers, shepherds and animals. The Broads and rivers provided glimpses of recreational pastimes, besides working wherries and windmills. Vast skies were reflected in these waters creating ‘blue’ Broads and silvery rivers in watercolour, oil and pastel. The painters, stepping off the traditional platform of portraits, on which Norwich had rested its laurels for centuries, relished the chance to learn landscapes. Pictures by earlier 18th century artists recording the Grand Tour, alongside the growth of large country estates (proud owners were now looking for artists to record these), had catalysed the change. By the 1820s, facing such challenges with fresh pigments becoming available, these artists would become important colourists – a fact often unrecognised. If John Crome cleverly renewed the Golden Age connection then John Sell Cotman, a few years later, brought about a colour revolution. It is these facts, together with occurrences elsewhere – witness Turner’s extravagant use of pigments – that made the Norwich School so aware of colour as a recording material, finding its way into characteristic leafy foliage.

Closer to home, Constable painted the partly wooded Wivenhoe Park, where Essex University stands today, in 1816. By 1820 he had completed Stratford Mill and, like John Crome, was at the forefront of tree painting. The idea of painting a large portrait of a tree, just one oak, half a century earlier might not have been very acceptable. Gainsborough’s view of Cornard Wood (1748), painted when he was eighteen, with a good dozen oaks, was the desirable Ruisdael method, with safety in numbers. However, by the second decade of the 19th century Crome proudly presented the single Poringland Oak to the world. It says much of his abilities that he could so successfully place this great tree in undulating countryside with children bathing in late afternoon light – under a cluster of sun-edged ‘Cuyp’ clouds. He had pulled one tree out of a famous Gainsborough landscape, as it were, and enhanced it to magnificence. This was as good an emphasis, tree-wise, as any that Norwich School painters could look to.

So it’s their landscapes that we search for evidence of past times. Just as Crome and Cotman still painted Mousehold Heath, north east of Norwich, as wide open land in spite of the Enclosures Acts, so there was romanticising of wooded lanes and reeded rivers in the Gainsborough and contemporary Constable fashion. It is little realised now that up to three-quarters of the tree population was then pollarded. The bare evidence of this ancient habit, ensuring longevity, is today best seen in winter: pollards, often straddling hedgerows, still stand majestic against the skyline. Many of these hedgerow boundaries were present when Romans carved their straight road system from Colchester to Bishops Stortford and Ipswich to Norwich, for aerial views reveal that fields had had corners amputated. The importance of wood for winter warmth meant regular pollarding. The whole nation depended on trees, Nelson’s ships being a prime example. The internal structure of buildings, of country houses and factories alike, required vast quantities. Along the East Anglian coast the need for shipbuilding remained strong. The great herring fleets out of Yarmouth and Lowestoft, in their heyday, depended on wooden luggers weighing thirty or forty tons. Darby’s timber yard at Beccles was just one port of call where trunks, some loaded on barges, journeyed to shipyards perhaps (fig 2). Rarely recorded, this scene was once commonplace.

Fig. 2, Barges at Darby’s timber yard, Beccles, by Alfred George Stannard, c 1850.

Pollarding trees required they be trimmed above animal head height. If trunks belonged to landlords then pollards belonged to peasants, by hook or by crook, the likely origin of the expression. Crome’s son, John Berney, followed in his father’s footsteps painting oaks and willows. One of John Crome’s most famous oil paintings is ‘Road with Pollards’. Its location had until now not been established. However, a chance discovery of a drawing, signed by his son, of a road with pollarded willows, reveals its location. It is inscribed ‘at Lakenham, near Norwich 1816’ (fig 3). Those who travel the A140 may well pass along here a mile or so before dipping into the city. There is plenty of foliage that could be pollarded as this drawing shows, which is more than can be said of Crome’s oil. When this painting was first illustrated, a century ago, it had exhibited nearly as much growth as the pencil drawing. But an overzealous cleaner partially pollarded Crome’s willows – they show a drastic reduction in bush – as, simultaneously, greater Norwich had wiped away Lakenham’s identity too. The odd lone leaf can just be spotted aloft, bereft of stalk, heading skywards!

Fig. 3, Pollards at Lakenham near Norwich, by John Berney Crome, 1816.

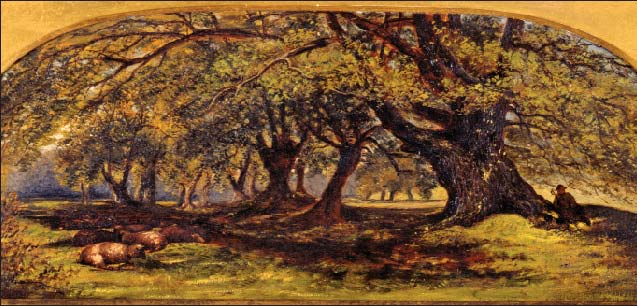

Both Hatfield and Epping Forests provided ideal places for studying ancient trees where hornbeams continue to grow in what was once part of a great forest that spread from Epping to Chelmsford and Southend. It was also known as Essex Forest or Great Waltham Forest. Waltham means ‘woodhome’ – from the Saxon ‘walt’ for wood, and ‘ham’ for home. James Stark, who painted oaks in Windsor Great Forest in the 1840s, instructed his son Arthur James. A.J. Stark’s view (fig 4), probably an Essex forest ride, portrays a shepherd under a hornbeam with its magnificent girth of centuries. Today, Epping Forest is the largest woodland area in Greater London, still covering 6,000 acres from Manor Park to Epping.

Fig. 4, Ancient hornbeams in an Essex forest, by Arthur James Stark, c 1870.

Trees, in open spots, had little problem growing lichens on sun-exposed bark. This resulted in silvery green tree trunks, as recorded by Norwich artists, unlike the dark hornbeams in Stark’s heavily shaded forest. The rise in industry and pollution would certainly have affected the county with its close proximity to London and a prevailing SW wind. Indeed, air pollution at Sibton’s measuring station in East Suffolk is consistently higher than in London, where the weighty pollutants have first arisen only to fall back to earth 100 miles distant. The sulphur in the air came to rob the trees of their lichens and even now their abundance has not returned to the growth formerly painted in East Anglia – so clearly demonstrated by Obadiah Short (fig 5). But, on cloudy days, direction finding in forests is still helped by locating clearings. Looking for trunks with lichens, and even leaves more loaded with seasonal colour, point the way south.

Fig. 5, Silvery lichens on wayside Norfolk oaks, by Obadiah Short, c 1860.

Obadiah Short pursued the Crome idiom. An amateur enthusiast, he walked one day from Norwich to Holkham to meet the Earl of Leicester. Was he pulled by the great estate’s trees? Starting in 1780, two million were planted over the next twenty years covering more than seven hundred acres with forty nine varieties. Perhaps he went to investigate to paint something of this enterprise. Collectively the school was a more detailed recorder of trees than any other, and this helps to define it, especially with Crome’s love of delineating more of trees’ anatomical structures than his contemporaries, Turner and Constable.

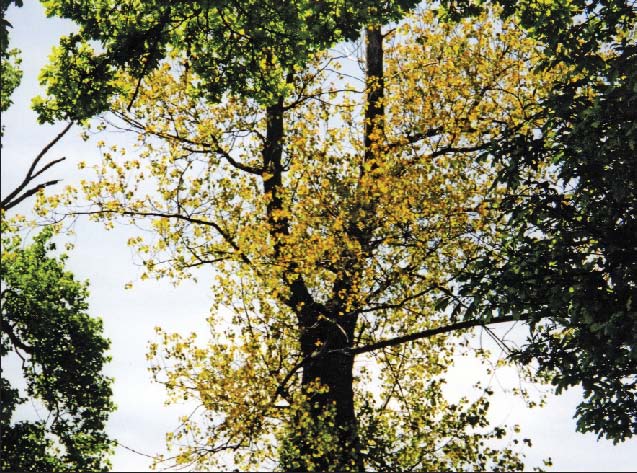

All their observations prove invaluable in trying to read the history of landscape. In mediaeval times the harvest festival was known as the Lammas festival. It was celebrated in August when, by coincidence, oak trees, and others, must have produced their second leaf growth, which could be russet, amber or even purple coloured on the sunny side of trees. Thus coloured, the term ‘lammas leaves’ was born. Artists chose to enrich their paintings by enlivening foliage colours, particularly on oaks, usually choosing an amber tint. Yet, today, this interesting colour change, which needs the sun’s rays to develop fully, can be observed in July, revealing evidence of climate change. Constable chose views along the Stour for his famous ‘six-footers’. The most striking and colourful tree in all of these is seen in Stratford Mill, and is now recognised as a black poplar. This sloping specimen, bathed by bright sunlight, and appearing translucent, becomes the focal point of the tree painting. A closer look reveals many a golden touch amongst this brilliant green leaf. In spite of the summertime image of boys fishing for minnows, these colours have long prompted art historians to pronounce that Constable was painting ‘autumn’. However, it might have proved tricky to demonstrate otherwise had it not been for the chance discovery of a hybrid black poplar in a hedgerow on the edge of the Stour valley, with matching colours, on the last day of May 2001 (fig 6). The tree has not repeated this striking phenomenon. Curiously Constable, a great observer of nature, could have muddled the foliage of a real black poplar, with its tendency to slant so conspicuously, with that of the quite similar hybrid variety, which tends to stand upright, as in the photograph. Botany books published as many as one hundred years later, understandably, also confused the two. The conclusion to be drawn is that Constable was recording an unusual natural event using these colours. This also happens to date it firmly to late springtime.

Fig. 6, Striking foliage, hybrid black poplar, near Sudbury, midday, May 31st 2001.

So colour, besides drawing, can be the key to reading more of ‘landscapes’. If you take a clod of clay and bake it, you get a red brick; if you grind it up, an earth pigment; and if you find an autumn maple, with luck, many a red leaf. Which all goes to prove, hook or by crook, the answer lies in the soil.

Peter Kennedy Scott

Peter Kennedy Scott is a retired GP. His interest in the Norwich School developed when he moved to Suffolk in 1967. In those days it was still possible to root out undiscovered Norwich School paintings from the back of antique shops and Peter was highly successful in identifying them. He is now seen as one of the leading experts on the subject, and catalogues for Christies, Sothebys and Bonhams.