Discovering Historic Wallpaper in East Anglian Houses

In the middle of our family farm at Bures there was an empty 16th century farmhouse neglected almost to the point of dereliction, and it was there that my teenage detective instincts were let loose for the first time. Layer upon layer of obscuring wallpaper was stripped-out and consigned to a bonfire in the garden to uncover the beams in the walls. Strangely, some of them were picked-out in red; others were thickly covered in whitewash across plaster and timber alike.

Nowadays we recognise the need to care for painted decoration in timber-framed houses. Suffolk has more wallpaintings than most counties. Although many of these, like the red studwork at Bures, are simple colour schemes dating from the 17th century, nonetheless they are an important part of history. What is still not

appreciated and enjoyed by most historic-home owners is that hand-blocked and beautifully-designed wallpaper can still survive from the early Georgian period, although perhaps only in fragments. In living rooms and bedrooms there are many attractive types of pattern. They become far more valuable to us when we understand them, so this article is intended to stir up interest – but please look carefully!

Many late 17th and early 18th century houses had walls lined-out with several types of textile. The cheapest were stained or painted cloths which might have floral or landscape designs on them. Another more delicate material was silk with embroidered and perhaps lacework designs. Tapestries were reserved for the very rich.

Block-printed wallpaper was introduced at the end of the 17th century as an unashamed simulation of the real thing. It was in the 1730s that wallpaper quite suddenly seems to have become fashionable in East Anglia, but at that time all production was centred on London. The painter-stainers who produced them made cards advertising their wares and describing alternative patterns available, and regional warehouses in Bury, Colchester and Ipswich would retail them.

Around ten years ago I was studying and recording the interiors of several commercial buildings in Bury St Edmunds as they were being stripped-out in advance of refurbishment. Historic paint conservator Andrea Kirkham was called in to protect and conserve the 16th and 17th century wallpaintings that were often found, and she pointed out that there was also a later generation of

wallpapers which well deserved analysis and care, if only by rescuing before consignment to a skip. I learnt rapidly how to tell the age and importance of the different types of wallpaper. Now I produce my own reports.

Figure 1.

The most valuable series of Georgian wallpaper fragments in any house I have seen so far was, surprisingly, in the extraordinary houses shoehorned into the ruins of the West Front of the Abbey of St Edmund in Bury. Their very successful refurbishment has just been completed. While, of course, the medieval ruins have great importance, the 18th century wallpapers in the first and second floor rooms show that there was a well-to-do and cultured occupier in about the 1730s and thereafter. The most important of the papers, and probably the earliest (see Figure 1) is a green rococo-inspired paper of about the 1730s. Rococo designs are delicate, feminine and a reaction against the severity of the Baroque that preceded it. Here the black and white abstract patterns interplay with leaf designs in a very sophisticated way. We think that this pattern may have been designed in France and manufactured in London, but what is especially interesting is the inclusion of a repeated glazed oval motif about 50mm high overlying a tree pattern. The room was a bedroom, and when the occupier walked in with a candle perhaps the shining ovals were intended to reflect like a hundred candle flames around the room. I am told that a much earlier wallpaper imported from China to Drayton House in Northamptonshire has the same oval glazed motif, so the idea must have been passed on to another generation.

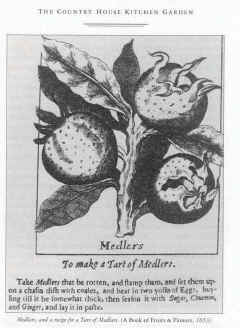

On top of this green paper was another quite different design, (Figures 2 and 3) perhaps about twenty years later. It was described by expert Anthony Wells Cole as a ‘painterly scheme’. A thick, high-quality paper was printed with realistic flowers, fruit and foliage on a white background. Among the flowers are medlars, a popular fruit in the 18th century.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

No 6 Angel Hill, now the Tourist Information Office for Bury St Edmunds, was completely rebuilt in 1696. Like many town houses it had a first floor drawing room overlooking, in this case, the market square now called The Angel Hill. In a blocked door jamb are fragments of another wallpaper design of about the 1730s or 40s. A simple pattern, again in black and white, has stylised foliage against a background of fine scrolling in white dots on a green ground. No doubt real silk embroidery

would have been done with a needle and silk thread. A very similar paper was used at Hull House, The Hythe, Colchester; perhaps the two designs came from the same factory (Figure 4). Sheets of this paper survive on the landing, but in very poor, faded and damp condition when discovered. It had a blue background. The flowers would have been picked-out in a colour, perhaps pink, but these have faded away. However, in the best bedroom of the same house strips of the same wallpaper design with a green background were found trapped behind a skirting. This is the ideal place to preserve wallpaper, and the strong green background and bright pink flowers are all in good condition after more than 250 years.

Figure 4.

At about the same time, some floral wallpapers were being produced with a ribbon design as a foil. The ribbon could appear to be folded or sinuous, dividing the floral motifs into diamonds or undulating between each floral spray (Figure 5). This grey paper was found at Lawshall Hall in the drawing room. It must have been applied just before 1752 when a map was made with a tiny drawing of the refurbished house. A beautiful published example (Figure 6) is illustrated in a recently-published book, The Papered Wall which gives a good overview of the history of wallpaper. This was produced in London and exported to Williamsburg, Virginia. English wallpaper was, by the mid 18th century, famous all over the world and huge quantities were exported to many European and American regions.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

At the end of the 18th century there was a new fashion in England for very plain understated designs, perhaps stylised or geometrical, often on a sombre background of grey or brown. Many papers had a uniform mesh called pinprint, small-scale dots of black or white with or without an overlying pattern, which itself could be abstract and simple. Of course, it would be expected that this type of wallpaper was merely a background to furnishings and fixtures, but the result was a complete loss of interest from the foreign markets. I have found many pinprint papers in Suffolk but here is an example at Curzon House, St Nicholas Street, Ipswich (Figure 7). In this instance there was a brightly-contrasting realistic floral border paper with deliberately eye-catching red and green colours. This type of realism was a copy of French designs, which by 1800 were far better in quality than the English versions. Panoramic, floral, architectural and landscape wallpapers were then produced in France to a quality which has never been exceeded since.

Figure 7.

On the whole early 19th century wallpapers in England plumbed new depths of boredom in colour and design quality, but from the 1830s onwards machine-made papers were being produced in such quantities and so cheaply that the humblest homes could afford them. The wide variety of pattern and quality available is well displayed at the Whitworth Museum, Manchester, which specializes in Victorian and later papers. Expertise on the finest Georgian designs can be found at Temple Newsam House, Leeds, or the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. A very rare example of rooms lined-out in wallpapers of the 1730s is at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, which is now a museum.

If any reader discovers Georgian wallpaper in their own house and would like it analysed, I would welcome contact. It is high time we had expertise of our own in Suffolk, based at one of the museums and with a wallpaper collection to encourage home-owners to discover and conserve their own Georgian wallpapers.

A recommended book on wallpaper design is The Papered Wall, edited by Lesley Hoskins, Thames and Hudson 2005.

PHILIP AITKENS

Historic Buildings Consultant

E-mail: ph.aitkens@btinternet.com

Tel: 01284 704756