Gainsborough’s House: Celebrating the Past and Looking to the Future

Gainsborough’s House is one of the few birthplace museums to feature the work of a single artist, and shows more of the artist’s work than any other gallery in the world. The historic interiors of the house provide an intimate experience for viewing paintings, drawings and prints by Gainsborough, from all periods of his career and across a wide range of genres. Now, a major capital development project, ‘Reviving an Artist’s Birthplace: A National Centre for Gainsborough’, will create custom-built exhibition galleries to display Gainsborough’s work in an adjacent building, allowing new possibilities for the presentation of the house, and providing greater opportunities to bring the stories of eighteenth-century Sudbury to life in innovative new ways.

The project will safeguard Gainsborough’s Grade I listed childhood home and garden, protecting the special atmosphere of the house for future generations. Drawing on the history of Gainsborough’s weaving family, we will tell for the first time the story of wool and silk weaving in Sudbury through a Weaving Gallery. We will also create a Landscape Studio, strengthening the connection with the surrounding countryside. Situated on a third level, this multi-functional space will give stunning views over the water meadows, fields and woodlands around the town.

This article takes a closer look at these two key themes – the Suffolk landscape, and the local silk weaving industry. These subjects are at the heart of our future plans and have enormous historical significance for the Stour Valley and the surrounding area.

Thomas Gainsborough and the Making of the Suffolk Landscape

Thomas Gainsborough is today remembered as one of the most significant figures in the development of landscape as a genre in British art. Born in the market town of Sudbury, Suffolk, in 1727, he was exposed to scenes of great natural beauty from an early age and spent much of his youth exploring the fields and forests surrounding his birthplace. Sudbury’s ancient water meadows, situated just a stone’s throw away from the family home in the Stour Valley, afforded the perfect opportunity for close encounters of the pastoral kind.

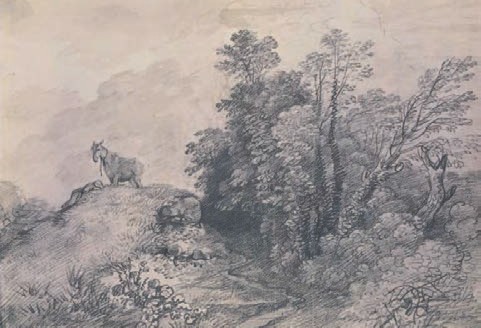

1 Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

Wooded Landscape with Cow, Cottage and Herdsman

Pencil on paper, c.1754.

As Gainsborough’s landscape studies suggest, the grassy banks, meandering pathways, and shallow pools – which to this day function as watering places for cattle – were of great interest to the young artist (Fig.1). Indeed, they remained so for the rest of his life: such subjects, which speak eloquently of the area’s essential character, were a constant point of pictorial return throughout his career. According to Gainsborough’s friend and early biographer, Philip Thicknesse, ‘there was not a Picturesque clump of Trees, nor even a single Tree of beauty, no, nor hedge row…for some miles round about the place of his nativity, that he had not so perfectly in his mind’s eye’. Gainsborough’s House today offers visitors a unique opportunity to view such artworks in the midst of the surroundings that inspired them.

In some contrast to the bucolic setting of Gainsborough’s childhood, in 1740 he was sent to London to train as an artist, aged just 13. Among the hubbub of the metropolis he studied at the St Martin’s Lane academy in Covent Garden, and soon after set up his own studio a mile or so to the east, on the edge of the City in Hatton Garden. In this urban context, Gainsborough’s experience of landscape inevitably became less directly shaped by his immediate physical surroundings, and more profoundly affected by his exposure to a variety of old and new artworks imported from the Continent. Through excursions to private collections, visits to auction sale previews, and many hours undoubtedly spent in coffee houses and print shops, where engraved images could be found in abundance, the budding artist would have had easy access to a rich body of source material to inform and inspire his own practice as a landscape painter (Fig.2). It is arguably this combination of early encounters with landscape that led to the development of Gainsborough’s distinctive approach to the genre, in which the real and imagined worlds are brought together to create harmonious compositions.

2 Anthonie Waterloo (1609-1690),

Landscape with a Winding Path through a Wood

Etching, c.1670s.

On the one hand, Gainsborough was powerfully inspired by the landscape he knew so well, and in particular the countryside of his native Suffolk. So many of his landscape paintings and drawings evoke a strong sense of place and convey an emotional attachment to the natural world that was familiar to him. At the same time, however, he was a fastidious student of past masters. He ardently subscribed to the academic conventions of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting, exemplified by the idealised landscapes of the Franco-Italian school. For Gainsborough, studying these masters’ works, and integrating their respective styles with his own, was an essential part of his practice as a landscape artist. This was something that he readily acknowledged. For example, when, in the 1760s, the Earl of Hardwicke attempted to commission from Gainsborough a landscape representing a specific view on his estate, the artist replied: “Mr Gainsborough presents his Humble respects to Lord Hardwicke; and shall always think it an honor to be employ’d in any thing for his Lordship; but with regard to real Views from Nature in this Country, he has never seen any Place that affords a Subject equal to the poorest imitations of Gaspar or Claude…If His Lordship wishes to have any thing tollerable of the name of G[ainsborough] the Subject altogether, as well [as the] figures &c must be of his own Brain”.

The relationship between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ in Gainsborough’s landscapes is neatly demonstrated by an early composition, now known only through an engraving published by John Boydell in 1747(Fig.3). Titled, A View near to Sudbury in Suffolk, the image offers a telling indication of Gainsborough’s developing style, and may be considered one of his first publically disseminated landscape compositions. The view takes in the surroundings of a manicured parkland setting – perhaps the formal garden of a local manor, or a picturesque corner on an estate belonging to one of the artist’s early patrons? A resplendent array of shrubs and trees form the backdrop for a series of ornamental ponds. Glimpses of distant buildings can be observed through gaps in the foliage. In the foreground, a trio of figures can be seen enjoying a picnic on a grassy bank; two of them tuck into food from a basket while the third swigs from a flagon. In the middle distance, two women engage in conversation by the water’s edge. Though an exact location is not provided, the caption beneath the image does suggest that it is representative of somewhere in the vicinity of Gainsborough’s hometown of Sudbury. Yet, in spite of this pretension to geographic specificity, we may question the extent to which A View near to Sudbury in Suffolk is really concerned with the accurate representation of a particular place not least because an identical version of the engraving was in the same year published with an alternative title: Drawn after Nature (Fig.4). With all suggestion of geographic specificity removed, this version perhaps invites us to consider the view in quite different terms. As the well-known Gainsborough scholar John Hayes once noted, the image is strikingly schematic in its formal construction. Moreover, the dainty characters are reminiscent of elegant figure studies by Gainsborough’s French drawing master, Hubert-François Gravelot. Although the composition and its cast of characters may well be rooted to a particular place and time, observed by the artist ‘near to Sudbury’, it seems in equal measure an expression of what he had learnt and achieved in London.

A similar reading may be made of Gainsborough’s panoramic vista of Landguard Fort – a military base on the Suffolk Coast, where the artist’s friend and patron, Philip Thicknesse, was Lieutenant-Governor. This picture is also now known only through an engraving, published in 1754 (Fig.5). The original painting succumbed to irreparable damage, reputedly from the salt water mortar of the wall in Thicknesse’s house on which it hung for many years. Both the painting and its engraved counterpart were commissioned by Thicknesse, who recorded the details of the commission in some detail: “as I wanted a subject to employ Mr. Gainsborough’s pencil in the Landscape way, I desired him to come and eat a dinner with me, and to take down in his pocket book, the particulars of the Fort, the adjacent hills, and the distant view of Harwich, in order to form a landscape”. In accordance with Thicknesse’s desire for a topographically accurate view, the caption beneath the engraving denotes that the orientation is ‘South East’. As per his request, the Fort, and Harwich, on a distant peninsular across the water, are both present in the picture. In the foreground of Gainsborough’s image there is a great deal of added liveliness and human interest; this is, perhaps, where the boundary between the real and imaginary becomes blurred. A male figure, who can be seen reclining on a fallen tree, is thought to represent Thicknesse himself. His seated position, with legs splayed, emulates a recognisable motif employed by Gainsborough elsewhere – most notably, perhaps, in his 1752 portrait of John Plampin, now in the collection of the National Gallery. Other notable features introduced into the landscape include a horse-drawn wagon disappearing down a winding path, and a sleeping shepherd on a grassy knoll: both distinctive components in other works by Gainsborough, and clearly part of his contemporary pictorial repertoire (Figs. 6 and 7). By offsetting the distant panorama of Landguard Fort with these kinds of details in a narrow strip of foreground at the foot of the picture plane, Gainsborough was evidently picking and choosing well-rehearsed designs to artificially enhance the scene and, in the artist’s own words, “create a little business for the Eye”.

3 John Boydell (1720-1804), after Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

A View near to Sudbury in Suffolk

Engraving and etching, 1747.

4 John Boydell (1720-1804), after Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

Drawn after Nature

Engraving and etching, 1747.

Figs 3 and 4 are different impressions of the same engraving, but crucially they have different captions beneath – one reads ‘A View near to Sudbury in Suffolk’ and the other reads ‘Drawn after Nature’. The fact that these alternative descriptions were used for the same image suggests that there is a fine line between ‘fact’ and ‘fiction’ in Gainsborough’s landscapes – especially those which purport to depict specific topographic views.

5 Thomas Major (1720-1799), after Thomas Gainsborough

(1727-1788) Land-Guard Fort in Suffolk

Etching and engraving, 1754.

These examples provide an intriguing framework for thinking about Gainsborough’s practice as a landscape artist. Clearly, for Gainsborough, the world he experienced physically, the world he inhabited imaginatively, and the world he saw through other artist’s eyes, were not fundamentally opposed: on the contrary, when it came to creating works of landscape, for him they were inseparable.

Sudbury and Silk

The formation of Sudbury, an historic market town situated near the River Stour on the Suffolk–Essex border, dates back to Anglo- Saxon times at the end of the 8th century AD. The name Sudbury, meaning ‘south borough’, distinguished the town from the settlements of Norwich and Bury St Edmunds to the north. By the 11th century, Sudbury was well established, appearing in the Domesday Book of 1086 as a market town.

Sudbury’s most enduring legacy has been as a centre for the production of textiles. Today, the three silk mills that carry on this proud legacy – Vanners Silk Weavers, Stephen Walters & Sons and Gainsborough Silks – produce roughly 95 per cent of the nation’s woven silken fabrics, making Sudbury the silk capital of the United Kingdom (Fig.8).

6 Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

Open Landscape with Country Wagon on an Undulating Track

Oil on canvas, 1746 – 1747.

Silk production originated in China over 5,000 years ago, spreading to Western Europe by the 11th century AD. For the last 200 years, Sudbury has been at the centre of silk production in England, its history dating back to the formation of the woollen industry in medieval Suffolk. Textile manufacturing was established in Sudbury by the 14th century, with the town specialising in heavy woollen broadcloth. Many of Sudbury’s nearly 250 listed historic buildings were constructed during this period; the fine medieval timber-framed structures housing the town’s prosperous cloth merchants.

7 Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788)

Wooded Landscape with Horse and Boy Sleeping

Pencil on paper with washes, c.1750s.

With the decline of the wool trade and the introduction of fashionable silk fabrics from China starting in the early 1600s, many Suffolk towns were forced to shift production to lighter- weight fabrics. This movement was aided by the influx of skilled Huguenot silk weavers from France, who had fled Europe in the late 17th century after King Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes, exposing them to widespread religious persecution. The resulting 500,000 Huguenot immigrants, many of them highly skilled in the textile trade, cemented the silk industry in England, with the London district of Spitalfields being the centre of production.

By the late 18th century silk weaving had come to Sudbury. Following the Spitalfields Act of 1773, which enforced strict wage rates in the London market, Huguenot weavers began moving production to the country, with the former wool towns of East Anglia ideally situated. The establishment of the firm Vanners, dating to 1750, followed just such a trajectory, with the French Huguenot Vanner brothers moving their silk yarn processing and weaving operations to the town in the 1870s. Similarly, Stephen Walters & Company began in Spitalfields in 1720, before moving to Sudbury in the mid-19th century. The town’s third working firm, Gainsborough Silk Weaving Company, was founded in 1903 and has been located in Sudbury since 1925.

Today, Sudbury’s silk mills produce everything from couture fabrics for the fashion industry to important interior furnishings for the country’s royal palaces and stately homes. To celebrate this rich and varied history, Gainsborough’s House will be staging an exhibition on historic silk in summer 2017, to run from 17 June to 8 October 2017. This exhibition will explore the local and national history of silk in England from the 18th century to the present day, focussing on the diaspora of silk manufacture from Spitalfields in London to Sudbury in Suffolk (Fig.9). Featuring paintings, drawings and prints in addition to pattern books, costume and dress fabric, this will be the first exhibition of its kind to explore the important legacy that silk manufacture has left on the history of Sudbury and Suffolk.

8 Silk weaving in action at Vanners, 2016.

9 Historic album of 19th century silk swatches, Vanners.

Peter Moore

Research Curator

Peter Moore obtained a doctorate in Art History from the University of York in 2013, undertaking a placement at Tate Britain as part of his studies. He has previously worked as Assistant Curator for the National Trust, and has also held the position of Researcher at The National Gallery. He joined Gainsborough’s House as Research Curator in April 2015. As part of the Museum and Gallery’s curatorial team he has staged a number of exhibitions including ‘The Painting Room: The Artist’s Studio in Eighteenth-Century Britain’ and ‘Gravelot: Designing Georgian Britain’. In 2016 he led a project to publish the Gainsborough’s House collection online; this open-access resource now has some 2,000 objects from the collection available for public viewing.