History of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds

Bury St Edmunds has a long and rich history of presenting plays, which can be traced back from the late 14th Century, when one of the church guilds performed during the festival of Corpus Christi, to the present day in the Theatre Royal. Indeed, one of the four surviving Mystery Play scripts is thought to be from the Bury St Edmunds Mystery Cycle. Later, John Lydgate, the leading 15th Century dramatist, lived in Bury, and there are references to the town in Shakespeare’s Richard II and Henry VI Part Two. Later still, in 1689, Thomas Shadwell, a former pupil of Bury School, saw his play, “Bury Fair”, performed at Drury

Lane. Throughout the years, plays were presented not only in the churches, but also in the 13th Century Guildhall, in the Abbey Gardens, and on Angel Hill in travelling theatre booths. A principal venue was the old Market Hall, destroyed by the fire which engulfed Bury in 1608, and replaced by an arcaded Jacobean building. The upper floor was converted into a theatre in 1734 by the Bury Corporation who later, in 1774,

commissioned Robert Adam to redesign and upgrade it, keeping the theatre on the upper floor, with the market below.

During the Georgian period, theatres across the country were grouped into circuits, Bury being part of the prestigious Norwich Circuit, which also included Norwich itself, Kings Lynn, Great Yarmouth, Cambridge, Ipswich and Colchester. The Norwich Company of Comedians travelled around the circuit, carrying their costumes, scenery and musical instruments, and spending six to eight weeks at each venue, normally coinciding with a special event in the town. In Bury’s case, their visit coincided with the Bury Fair in late October/early November. The Fisher Circuit, of lesser importance, was also operating in East Anglia and visited theatres in Sudbury, Woodbridge, Newmarket, Bungay (where the Fisher family resided) and Lowestoft, to name but a few. Then there were Fit-Up theatres, visited by assorted companies, who would convert barns and other suitable buildings for their performances. These included Dedham, Clare, Hadleigh and Stoke By Nayland. Finally, the simplest and cheapest form of drama, presented in travelling booths, could be quickly erected on village greens or in town squares.

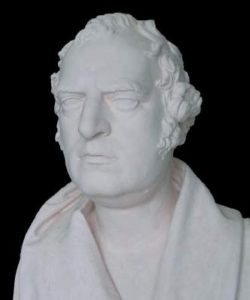

William Wilkins

Since 1768, the Wilkins family had owned shares in the Norwich Circuit of Theatres. In 1799, William Wilkins senior took overall control of the circuit. He was a builder and designer of theatres and he also had a talented son, William (1778-1839), who had ambitions to become an architect. After leaving Cambridge University, he travelled on a scholarship to Taormina, in Sicily, where he was inspired by the ruins of their beautiful Greco-Roman open-air theatre to build a new theatre in Bury to replace the one in the Market Cross, which was proving to be too small for Bury folk, who had made it the most profitable on the circuit. It only held 350. William Wilkins saw an opportunity to increase the capacity to 780 and so boost profits. Before then, however, he designed Downing College, Cambridge. He was to become a leading neo-classical architect and later went on to design University College in London and the National Gallery.

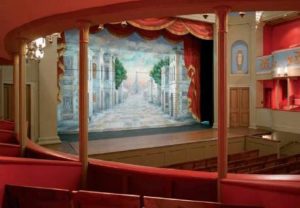

In 1818, he bought a piece of sloping ground near Westgate Street, at the southern edge of Bury. The gradient, following classical tradition, meant that excavation costs were reduced. He chose a simple, symmetrical Doric style, with an open arcade and fluted columns. This symmetry was continued within the building, where the emphasis was on geometric principles and proportions which, in turn, produced perfect acoustics and good sightlines. The existing stage area today is of exceptional significance as almost all of this original structure: walls, roof, scene dock are retained, together with the proscenium arch. The acting took place on a forestage in front of this arch, and special effects, beloved of Georgian audiences, took place on the stage itself. Scenery would be lowered, using a complicated rope system, and flats slid in from the wings in special grooves. There were trap doors, waterfalls, drifting clouds, bobbing ships and all manner of sound effects. The auditorium was lit by oil lamps, which remained throughout the performance. This practice was continued even after gas was introduced in 1838. By 1906, however, electricity was installed, which enabled the stage to be illuminated, allowing the Auditorium to be in darkness. Interestingly, though the capacity of this new theatre was 780,

today it is only permitted to house 350. Plus ca change…

The new theatre opened on 11th October,1819 with two plays: “A Roland for an Oliver”, a French farce; and “John Bull”, patriotic and British. The audience had a choice of Dress or Upper Circle boxes, if they were “Polite Society”; the Pit, if they were merchants, shopkeepers, playwrights and the like; or the Gallery if they were the Hoi Polloi and likely to make the most noise and launch disapproving missiles. Mind you, the posh lot talked a lot, engaged the actors in banter and generally rubbernecked the rest of their kind, sporting the latest fashions and gossiping with all the right folk. Segregation ruled supreme. William Wilkins had achieved his dream and by then had taken over the running of the circuit from his father. Above all, Bury now had a purpose built theatre. The Norwich Company of Comedians continued to travel the circuit. Their performances were popular, consisting of a main play (perhaps Shakespeare or Sheridan), after-pieces (short scenes), dancing, music and a variety of other entertainments. Occasionally, they were joined by well known actors. Such was William Charles McCready, friend of Charles Dickens, who in 1828 combined with the Norwich Company for a week in November and took the lead in five separate plays. On another occasion, in the same year, a certain Monsieur Gouffe, dressed as a monkey and, suspended only by his neck, descended from the Gallery to the Stage, waving two flags and carrying a small boy under one arm. He was a “Man of Spectacle “, who performed spectacular feats.

The new theatre opened on 11th October,1819 with two plays: “A Roland for an Oliver”, a French farce; and “John Bull”, patriotic and British. The audience had a choice of Dress or Upper Circle boxes, if they were “Polite Society”; the Pit, if they were merchants, shopkeepers, playwrights and the like; or the Gallery if they were the Hoi Polloi and likely to make the most noise and launch disapproving missiles. Mind you, the posh lot talked a lot, engaged the actors in banter and generally rubbernecked the rest of their kind, sporting the latest fashions and gossiping with all the right folk. Segregation ruled supreme. William Wilkins had achieved his dream and by then had taken over the running of the circuit from his father. Above all, Bury now had a purpose built theatre. The Norwich Company of Comedians continued to travel the circuit. Their performances were popular, consisting of a main play (perhaps Shakespeare or Sheridan), after-pieces (short scenes), dancing, music and a variety of other entertainments. Occasionally, they were joined by well known actors. Such was William Charles McCready, friend of Charles Dickens, who in 1828 combined with the Norwich Company for a week in November and took the lead in five separate plays. On another occasion, in the same year, a certain Monsieur Gouffe, dressed as a monkey and, suspended only by his neck, descended from the Gallery to the Stage, waving two flags and carrying a small boy under one arm. He was a “Man of Spectacle “, who performed spectacular feats.

All of this, of course, hinted at the need to attract larger audiences. By the 1840s, the theatre was struggling. The railway had come to Bury and the richer clientele had an opportunity to travel to London. William Wilkins had died in 1839 and by 1843 the whole Circuit System had ended. It was becoming too expensive. Instead, theatres began to provide their own fare. In 1844, the celebrated Madame Vestris, a contralto who sometimes played male roles and who managed both the Lyceum and Covent Garden theatres, visited Bury. She is regarded as a prominent figure in the history of the British theatre and customs of the nineteenth century. Lily Langtry was booked to appear but went to America instead. There was a popular demonstration of the new phenomenon, the Phonograph, in 1891; and the following year “Charley’s Aunt” by Brandon Thomas had its first night in the theatre and went on to become an enduring success across the world. Then, in 1898, the theatre was visited by Colonel Crocker from America with his troupe of thirty educated horses and mules “without bridle or rein“, who could jump higher than themselves. He was a nineteenth century horse whisperer.

As the theatre entered the new millennium, change was required. A new breed of playwrights had emerged (Ibsen, Shaw, Chekhov) and were writing naturalistic drama, which did not allow for the sort of audience intrusion, practised by Georgian audiences. The forestage and stage boxes disappeared, and the acting now took place behind the proscenium arch, made possible by the new electric lights. A bar was added to the front of the building (William Wilkins must have twitched in his grave) in response to audience demand and the need to increase income. As the Edwardian period ended, society was gradually changing. Socialism and the Suffrage Movement, followed by the ravages of the Great War, had a huge impact on live theatre, which was already struggling. Bury was no exception and, in 1920, Greene King Brewery bought the theatre and attempted to breathe life into it. By 1925, the effects of cinema, particularly from America, made the chances of its survival even more remote and it was closed in 1925. Nearly all the theatres on the Norwich and other circuits had closed or been demolished by now, but the Theatre Royal was fortunate. It stood in the middle of the Greene King empire and so could be put to good use by the Brewery. Thus, it became a barrel store for 40 years. Importantly, though, the structure remained virtually intact and only the seats were removed. It was here, surrounded by barrels and in lonely contemplation, that the storekeeper claimed the only sighting of a ghostly apparition seen in the theatre: a Georgian lady in all her finery moving effortlessly across the Upper Circle. Given the circumstances, its provenance is, perhaps, a trifle suspect.

From 1903, the Bury Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society had performed at the Theatre Royal, but when it closed they found refuge in the newly built Playhouse Cinema (now Argos). Years later, during the 1950s and 1960s, with the advent of television, the Playhouse itself was forced to close, and the Operatic Society again found itself homeless, until it was remembered that there was a perfectly good theatre nestling under a pile of Greene King barrels. Fortunately, the Brewery were supportive, a fundraising committee soon raised over £40,000, and the theatre opened again in 1965. The configuration was different; there was a central aisle, for instance, but it was up and running. In 1975, Greene King leased it to the National Trust, who in turn leased it to a management company, both for peppercorn rents.

Over the years, the format of the original Regency theatre has changed to meet the needs of the times but in 2005, under the artistic direction of Colin Blumenau, the theatre closed for two years to undergo a major restoration of its original form: a late Georgian playhouse and, moreover, the only surviving Regency theatre still in existence.

Over the years, the format of the original Regency theatre has changed to meet the needs of the times but in 2005, under the artistic direction of Colin Blumenau, the theatre closed for two years to undergo a major restoration of its original form: a late Georgian playhouse and, moreover, the only surviving Regency theatre still in existence.  Not only that, but it is the oldest working theatre in the country after Bristol and Richmond, Yorkshire and, importantly, one of only eight Grade One listed theatres in the country. Most of our early theatres have been destroyed or burnt down. The current Drury Lane theatre is the fourth on the site, for example.

Not only that, but it is the oldest working theatre in the country after Bristol and Richmond, Yorkshire and, importantly, one of only eight Grade One listed theatres in the country. Most of our early theatres have been destroyed or burnt down. The current Drury Lane theatre is the fourth on the site, for example.

The current theatre reopened in September 2007 with a lively production of “Black Eyed Susan” by Douglas Jerrold, a leading Georgian playwright. Its new format mirrors, as closely as possible, its original style. However, the stage is now flexible and allows use of a forestage, an apron stage and more conventional performance behind the proscenium arch. It is also possible to create a theatre in the round, with actors performing over the Pit and the audience completing the “fourth wall” on the stage. A magnificent new bar area (“The Greene Room”) was also created alongside one of the original side walls.

The current theatre reopened in September 2007 with a lively production of “Black Eyed Susan” by Douglas Jerrold, a leading Georgian playwright. Its new format mirrors, as closely as possible, its original style. However, the stage is now flexible and allows use of a forestage, an apron stage and more conventional performance behind the proscenium arch. It is also possible to create a theatre in the round, with actors performing over the Pit and the audience completing the “fourth wall” on the stage. A magnificent new bar area (“The Greene Room”) was also created alongside one of the original side walls.

Today, the theatre offers a richly varied programme of professional and amateur work. There is a strong youth theatre and an established Children’s Festival in the Summer. It is very much part of the local community and does valuable work with, amongst others, the Women’s Refuge, the Drop in Centre and Focus 12. It offers lunchtime concerts, literary talks and can even be used as a wedding venue. It has good wheelchair access, a loop system and can provide captioned performances, audio description and touch tours for the blind and visually impaired, sign language and relaxed performances. Its heritage is preserved through rehearsed readings of Georgian plays, full tours of the theatre, local history talks and considerable research. It is much loved by actors and audiences alike, and wonderfully supported by its many friends. Next year it celebrates its 200th birthday. William Wilkins must be proudly at rest.

Rory O’Brien

Rory O’Brien is a retired schoolmaster and has, for a number of years, been a Duty Manager at The Theatre Royal. I am grateful to Rory for writing the above article and for having proof read the Magazine for the eleven years I have been Editor. He, like me, feels it is now time to retire.