The House of his Dreams: Reimagining The Munnings Art Museum

The Munnings Art Museum is at Castle House, the former home of Sir Alfred Munnings (1878-1959) and his second wife, Violet. The museum is run by an independent, charitable trust established in the early 1960s by Lady Munnings, in accordance with her husband’s wishes to make his work more accessible to the public. Today, the museum is run by a small number of paid staff and a large and dedicated team of 75 volunteers.

Castle House and grounds

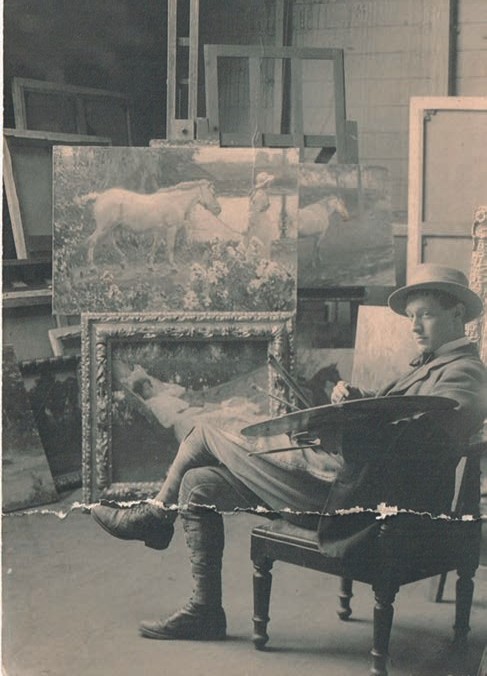

Alfred Munnings aged around 25

When Munnings found and bought Castle House in 1919, aged 40, he called it “the House of my Dreams” standing, as it does, close the to the river Stour and only a stone’s throw away from Constable’s Flatford. Acquiring the house, however, also filled him with trepidation. In his autobiography he writes: “Still full of fears,

“I began to wish I had never thought of buying such a thing as a gentleman’s residence. I should never be able to keep such a place! Who was I? A mere painter… what could I do with it?”.

When I took up the newly created role of full-time Museum Director in late 2013 it was with similar trepidation. I arrived with the remit to raise the profile of the museum and establish it as a national and, potentially, an international centre for understanding the art of Sir Alfred Munnings, recognised as one of Britain’s greatest equestrian painters. Munnings’ blustery character and outspoken opinions on art, particularly in terms of his role of President of the Royal Academy in the 1940s, have sidelined him both critically and in his popular appeal. This article is intended to offer a sense of the life of the man himself, and also to introduce you to some of the changes my team and I have made to the way in which the museum and its collection are now managed, interpreted and presented.

AN ARTIST’S LIFE

Sir Alfred Munnings was an extremely prolific artist and there are over 4000 finished works by him in museums, galleries and private collections globally, but for the purposes of illustration in this article I shall only refer to pictures in the museum’s own collection.

Wallpaper from the nursery at Mendham Mill, 1880s

Alfred James Munnings was born on 8th October 1878 at the Mill House, Mendham, beside the River Waveney on the Norfolk / Suffolk border. He was the second of four sons of mill-owner John Munnings and his wife Emily. He loved making pictures from an early age and was fascinated with capturing the equine form. He described horses as “my supporters, friends – my destiny, in fact … my life interwoven with theirs – painting them, feeding them, riding them, thinking about them.” He captured them not only from life, but they filled his imagination as this piece of wallpaper, recovered from the nursery wall at Mendham Mill, shows.

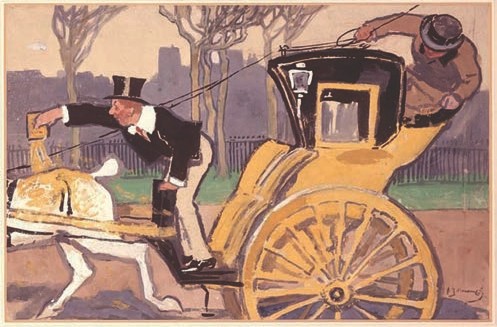

Munnings was educated variously at home, at the local school and at Framlingham College before, in 1892, at the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed to the Norwich based printing firm, Page Bros. & Co. for six years and trained to design posters and product wrapping. The 1890s was the decade in which artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha elevated the status of the poster to fine art, turning the streets of Paris, Milan and Berlin into public art galleries and ushering in the modern age of advertising. Munnings quickly became engaged in capturing the popular aesthetic style and was clearly aware, even at such a young age, of what made a commercially desirable image: “As those years went on, my designs must have brought a great deal of business to Page Bros. & Co., Ltd., of Norwich, for I often had more work handed to me than I could cope with … I always had a design ready, and more often than not the firm got the order”.

Original design for a Colman’s mustard advert, 1892-1898

Two of Munnings’ major clients at this time were the local Norwich firms of Colman’s Mustard and Caley’s, who made pulling- crackers and later chocolates. Caley’s Director, John Shaw Tomkins, was so impressed with the young apprentice’s design work that he became Munnings’ patron, taking him on trips to Europe and introducing him to European art through visits to museums and galleries.

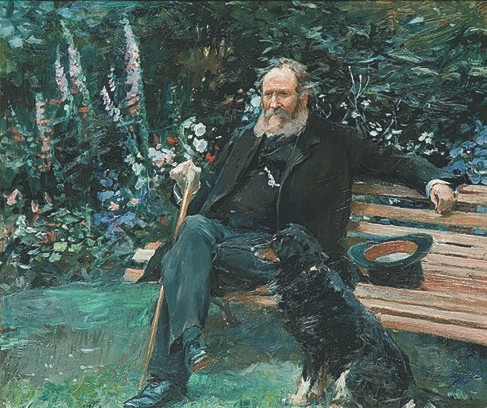

Daniel Tomkins and his Dog, 1898

In Norwich, Munnings also attended classes at the Norwich School of Art. Here, he received a traditional training in good draughtsmanship. After his apprenticeship finished, Page Bros offered Munnings a position but he declined, determined instead to make his own way in the world. One of his first commissions came in 1898, from Tomkins, for this portrait of his father:

This picture shows the young artist’s remarkable sympathy for his sitter, capturing the character of the old man who relaxes on a bench with his faithful friend, Trimmer. As well as being a first commission, this picture is also one of the last that Munnings would complete with sight in both eyes. In 1899, at the age of 20, damage caused by a bramble whilst lifting his dog over a style, caused him to lose sight in his right eye. He later wrote “This has been a handicap to me always … What wouldn’t I give to see with two eyes again!”

Despite having to take a year off painting to recover from his accident, 1899 proved to be a year of some success. Munnings had his first paintings accepted for the Royal Academy’s annual

Summer Exhibition, and he would continue to have works exhibited there every year, virtually uninterrupted, until his death in 1959.

Path to the Orchard, 1909

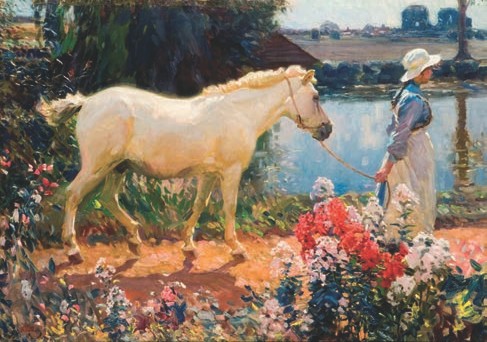

In the first years of the 20th century, Munnings experimented with pastels, watercolours and oils. Attending the Académie Julian in Paris and drawing and painting, either in his studio at Mendham or outside “en plein air”. The historic influences of Gainsborough, Constable and the Impressionists can all be seen in his work at this time, but he soon began to develop his own inimitable style and techniques. Looking back, he remembers “Fresh discoveries of all that paint could do led me on … What joy there was in finding out and seeing colour – becoming aware of beauties in everything, beauties never seen before.”. Munnings appreciated the appeal of the rural scene, and some of the museum’s now most popular pictures depict the Ringland Hills and countryside around Norwich. They also include a number of gypsy models.

By 1910 Munnings had long been aware of the Newlyn School of Art in Cornwall and the quality of light in that part of the country which had drawn artists there since the 1880s. In 1911 he decided to settle south of Newlyn in Lamorna Cove. There was already a small group of working artists who included Samuel John Lamorna Birch and Harold and Laura Knight. Munnings’ natural charisma and skills as a raconteur ensured that he quickly became a central figure within the colony. Laura Knight, who remained his lifelong friend, recalls the vitality he exuded “He was the stable, the artist, the poet, the very land itself!”. It was in Cornwall that Munnings met his first wife, Florence.

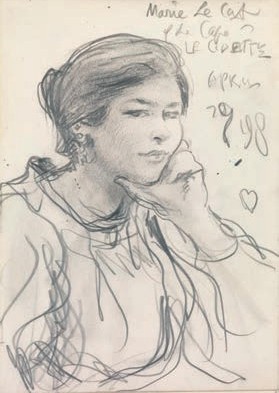

After the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Munnings made various attempts to enlist in the forces but was always rejected on the grounds of the blindness in his right eye. In 1916, with the help of an acquaintance, he began work as a strapper with the Remounts at Calcot Park, Reading. Using his familiarity with horses, he would check over and care for them as they arrived from Canada before being moved across the Channel for active service in France. Then, in 1918, Munnings was selected by the art critic Paul Konody to go to France as an official war artist for the Canadian Cavalry Brigade. During his time there he produced a number official paintings of officers, men and horses. He also made many informal pencil and painted sketches that provide a more personal glimpse of life behind the Front.

French Barmaid, 1918

1919 proved a pivotal year for Munnings. After returning from France, a collection of his pre-war Cornwall paintings sold to a London gallery. This gave him the “the nest egg” he needed to purchase a house – he had studios in London, Cornwall and Norfolk still and his horses and belongings were scattered between them – so, Castle House, was found and bought for the sum of £1800.

In addition, forty-five of Munnings’ Canadian Cavalry Brigade paintings were exhibited in the Canadian War Records Exhibition at the Royal Academy. Of particular note was a portrait of General Seely on his war horse, Warrior. Warrior was later the subject of a book, written by Seely, later Lord Mottistone, and illustrated by Munnings.

echoes the same sentiments and is a direct criticism of the Tate gallery, whom Munnings considered a proponent of Modern Art. The painting’s critical impact is almost non-existent today but its contemporary audience would have greeted it with an affirming chuckle. The New York Times cited it as reminiscent of William Hogarth’s comments on his 18th Century contemporaries.

1919 was also the year Munnings met Violet McBride who was to become his second wife. An accomplished horsewoman, Violet had the society contacts to build Munnings’ commission work and the 1920s and 1930s witnessed the consolidation of his extremely successful artistic career and firmly established his reputation as the most masterful painter of horses since George Stubbs. By the time Munnings produced this picture, the iconic “My Wife, My Horse and Myself”, he was an established artist with a constant flow of commissions. Each of which would command in the region of £500, the equivalent of £35,000 today.

My Wife, My Horse and Myself, 1928-1935

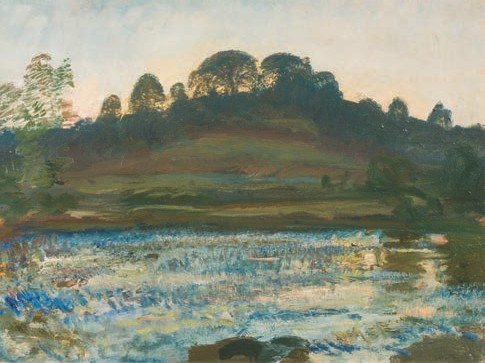

After the Second World War was declared in 1939, it wasn’t long before Castle House was requisitioned by the military. Having buried the contents of his wine cellar under the floor of his studio, Munnings escaped to Exmoor. He and Violet took up residence in Withypool, where Munnings set up a studio in the Royal Oak pub. Away from the constraints of paid work, he spent time making studies of the surrounding landscape, a subject for which he had a passion. Towards the end of the war, in 1944, Munnings was elected President of the Royal Academy. He was also knighted by King George VI.

In 1949, Munnings marked his retirement from the Royal Academy with a contentious speech. In it he vociferously condemned modernism as “a foolish interruption to all efforts in art”. The speech, which was broadcast live by the BBC, received widespread support at the time but it also contributed to a critical side-lining of his artistic achievements. His picture, “Does the Subject Matter?”, completed in 1956 towards the end of his life,

Brightworthy Ford, Withypool, 1940-1945

Does the Subject Matter?, 1953-1956

Following his retirement, and generally released from the constraints of commissions, Munnings was able to indulge in his lifelong love of both horses and the countryside as the source of inspiration for the paintings he now produced. The horses and jockeys at the start of races at Newmarket, and the local landscapes and skies, were his subjects of choice in the majority of these later works.

Under Starter’s Orders, Newmarket Start, Cries of ‘No, No, Sir’, 1956

After a spell in the Colchester hospital, Munnings died in his sleep at Castle House on 17th July 1959. His ashes are in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral, where his commemorative tablet is placed beside that of another great local artist, John Constable. There was a retrospective exhibition at the Royal Academy in 1960 in honour of Munnings’ life and work.

RE-PRESENTING THE MUSEUM

As a museologist, curating The Munnings Art Museum has become an all-absorbing endeavour. It is thrilling, thought- provoking and rewarding. Opportunities and challenges are thrown up on a daily basis. From the very first moment I entered the museum I was overwhelmed by the unique nature of the place and its collection. In my many years as a museum professional, working in extraordinary buildings and with millions of objects, I have never come across such a comprehensive single artist collection – or indeed a collection of any kind. The Munnings Art Museum is really quite a rarity – it is a museum that can not only exhibit the work of a world class artist but also demonstrate his working practices, make observations about his thoughts and opinions on art – and life – and be able to do this in the unique domestic ambience of his own home, surrounded by his working tools, personal effects and all the other ‘stuff’ that comes with having a wife, a home and a social life.

It was at the beginning of 2014 when my team and I started to address the ways in which we could energise the museum’s displays. They were, at that time, beginning to stagnate. The pictures had been hung much like they are in a home: beautiful to look at but often randomly placed. Some pictures occupied some spaces purely for practical reasons of size or shape. I noticed that, even with the support of our dedicated and knowledgeable volunteer stewards, there was a certain amount of confusion about what visitors were looking at and why.

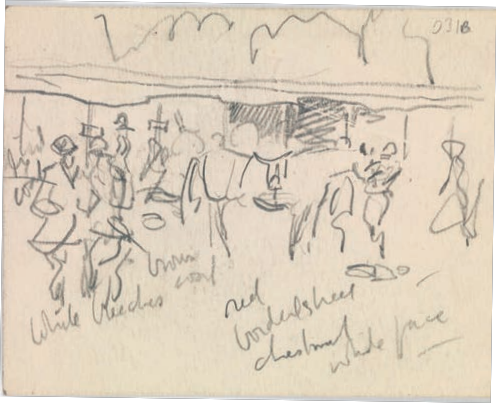

The museum’s collection is really quite representative of Munnings’ seventy year career. It consists of 650 oil paintings and a good number of watercolour paintings and is augmented by a small number of loans in from private and public collections. Significantly, and possibly uniquely for an artist of this stature, the collection comprises material with a unique ability to illustrate the process Munnings went through in the creation of a picture.

In addition to the museum’s painting collection there is a substantial archive. This holds hundreds of loose drawings and sketchbooks, catalogues and press clippings books, personal correspondence and photographs, books and other ephemera. The museum also benefits from owning much of the original furniture and many personal items belonging to the Munnings and Lady Munnings and the contents of his studio, his brushes, paints and props.

Sketch done at the races, 1930s

After joining the museum, I soon realized that there is a very real appreciation of the special nature of seeing the artist’s work displayed throughout his former home and working studio. All these elements combine to create a huge potential resource for developing unique, intimate, revealing – and changing – visitor displays. So, when my team and I began to search for the best way of presenting all these facets together in a clear and engaging way, it was probably unsurprising that a chronology or timeline suggested itself as being the answer.

As we began selecting pictures for the timeline, we really felt we were establishing a clear sense of Munnings’ development as an artist. However, we were aware of moving towards a more recognisable concept of a ‘gallery’, and away from a sense of a home and this was particularly emphasised by the decision to add at least one ‘traditional’ introductory text panel to each room. We were extremely conscious of maintaining Munnings’ personality within the displays, and with this in mind we decided to weave him into as much of the interpretative text as possible, using quotes from his autobiography and other correspondence. Writing as a relatively old man, Munnings’ memories vividly conjure people and scenes, realisations and doubts, from across his life, and he commits them to paper; in doing so gifting us with a real sense of the context (artistically, socially and personally) in which his paintings were made.

The Main Hall of the Museum

The chronological displays were opened at the beginning of 2015 and immediately we began to get positive feedback on the new approach. Visitors spent longer absorbing the new information and became more engaged with Munnings’ life story. Their feedback also included comments about the ambience of the museum and demonstrated that we had been able to maintain the homely feel despite this new approach to the exhibitions. One such visitor comment summed it all up: “I like the way you have both the feel of a lived in house and labels for the paintings. A unique balance of gallery and home.”

The newly decorated galleries

As well as completing the timeline displays, we redecorated two rooms at the back of the museum and installed museum grade showcases. The rooms are now dedicated to a programme of special ‘in focus’ exhibitions looking, in depth, at aspects of

Munnings work. The showcases allow us to display drawings, sketchbooks and other ephemera too fragile to exhibit previously. Our new exhibition, In Focus: Munnings and the River opens in April 2017. This exhibition, with over forty oil and watercolour paintings, sketches, photographs and personal ephemera including correspondence between Munnings and his friend, the Poet Laureate, John Masefield, will explore Munnings’ artistic and literary responses to a subject with which he had a great affinity and which remained a constant motif throughout his life’s work.

September Afternoon, 1939

Jenny Hand

Museum Director

The Munnings Art Museum is open: 1 Apr-29 Oct 2017, Weds– Sun & Bank Hol Mons, 2pm-5pm

The Garden Café from 10am – 5pm on days when the museum is open.

The Munnings Art Museum, Castle Hill, 1 mile south of Dedham village, Essex, CO7 6AZ Tel: 01206 322127 / e-mail: office@munningsmuseum.org.uk

Jenny Hand has been the Director of The Munnings Art Museum since July 2013. Having gained a post graduate qualification in Museum Studies from Leicester University, she has worked in several museums in the Midlands and spent ten years at Brighton Museums and Royal Pavilion managing large curatorial projects.