Long Melford – ‘Suffolk in a day’

It has often been said, and I know not from where the quotation sprang, that if you have only one day to discover Suffolk then visit Long Melford. It is easy to appreciate the sentiment because the village – though many would call it a small town – has more than its fair share of Suffolk’s finest historic buildings and they are set within a landscape immortalised by Gainsborough. It has the most dramatic Village Green in the county, dominated by one of England’s most spectacular medieval parish churches, creating a picture once seen never to be forgotten, while two remarkable Tudor mansions invite one to step over their thresholds (for a moderate charge) to explore their interiors.

Long Melford has thankfully had its bypass for twenty years or more so one can meander down the full length of the main street and enjoy its many delights in relative comfort. It is best to approach the village from the Sudbury side so that one reaches The Green as a fitting climax. One first of all savours the 19th century industrial flavour of the village with the conversion of the disused railway station and maltings into popular residential apartments and houses. It is close to here where the main thoroughfare aligns with the Roman road from London on its way to Ixworth and The Peddars Way.

Very soon medieval Melford begins with Chapel Green to the right and Melford Place, now a farm, opposite. This was once a large 15th century mansion and the home of the Martyn family whose tombs and chapel are a feature of the church. The mansion was built with a main hall block with cross wings at either end. From the 17th century onwards it gradually diminished in size until 1967 when most of what remained was destroyed by fire.

However, by a miracle, the private chapel with its fine timber roof survived intact. So did the excellent collection of Renaissance style carvings which had formed part of the family pew in the church until the 19th century. They are still beautifully cared for by the owner’s family who have been here since 1790. Melford Place is a private residence and not open to the public.

Chapel Green, opposite, takes its name from the chapel of St. James which the Martyn family cared for and which stood close by the tree. Alongside was the site of the Market which King John granted the village in 1214 together with an annual fair. In later years both market and fair were located on The Green.

From this point the street widens and is lined on both sides with houses of various dates and styles. A great many of them have 14th or 15th century interiors with later facades added. They combine to create a street scene of great interest and character: Georgian and Regency facades of red and white brick, Venetian windows and pedimented doorcases abound (four of the former on one house!) interspersed with timber-framing and lath and plaster. There are several examples of timber-framed houses with good plain 19th century fronts and one wonders whether it was economy or sentiment which resulted in the conservation of so many medieval interiors by those Victorian houseowners.

Eventually one reaches the handsome timber-framed Bull Hotel, once a cloth merchant’s house, and the equally interesting Brook House opposite. Beneath the thoroughfare you have traversed is the site of another village, shrouded in mystery and without a name. It was one of the largest Romano-British settlements in Suffolk and occasionally evidence is uncovered to prove the fact.

One crosses the Chad brook, which flows into the Stour a short distance away, and is confronted by the splendour of the huge triangular Melford Green sweeping up towards the church. Flanking it on the right is the smouldering red brick mass of Melford Hall with its six octagonal Tudor turrets towering above the moated site.

This house was built to impress and the builder was a Melford man who had become a monk at the great Benedictine Abbey of St. Edmundsbry and risen to become its Lord Abbot. The manor of Melford had been presented to the abbey by the mother of Edward the Confessor (c. 1045-65), and from then until Henry VIII closed the monasteries the abbots used it as a country retreat.

The man who built the greater part of the hall that dominates the Green was Abbot John Reeve. He held that post from 1515 and commenced work on his pleasure palace around 1520. At St. Osyth, the Abbot John Vintoner built a mansion for his personal use though attached to this abbey. The Abbot at Forde in Dorset did much the same thing while the great Cardinal Wolsey had a building frenzy at Hampton Court to create his own pleasure palace in which to entertain foreign diplomats and his sovereign, Henry VIII.

The six turrets with their domed caps at Melford Hall were probably inspired by those at Richmond Palace, just as the centre of the west front echoes Wolsey’s great gatehouse at Hampton Court. However, here it serves as a grand ceremonial entrance, giving direct access into the screens passage of the Great Hall, a unique and dramatic innovation of great historic interest.

In Reeve’s time the kitchens were placed well away from the main building and one of the more interesting surviving features is the major part of a beautifully constructed brick tunnel leading from the kitchen to the basement serving room.

At the dissolution of the Abbey in 1539 the house was surrendered to the Crown together with its other possessions, which covered much of West Suffolk.

The Manor of Melford was thereafter leased by William Cordell, son of a cloth merchant from Edmonton, who had settled in Melford. He became Master of the Rolls and served the last four Tudor monarchs and was thereby granted the Manor outright. For many years it has been claimed falsely that he rebuilt the Hall and only recently, in their new Guide Book to the house, has the National Trust begun to suggest that he may not have done so.

The house was remodelled in the 17th century and refurbished in the 18th and early 19th centuries, but much of Reeves original work has survived. The Hyde Parker family acquired the house in 1786 and live there still.

I will not attempt to do justice to the splendour of Holy Trinity church in this short article, but I will focus on one exceptional feature of this remarkable building which deserves to be appreciated more for what it represents. I refer to what is called the Lady Chapel, annexed to the east end of the church.

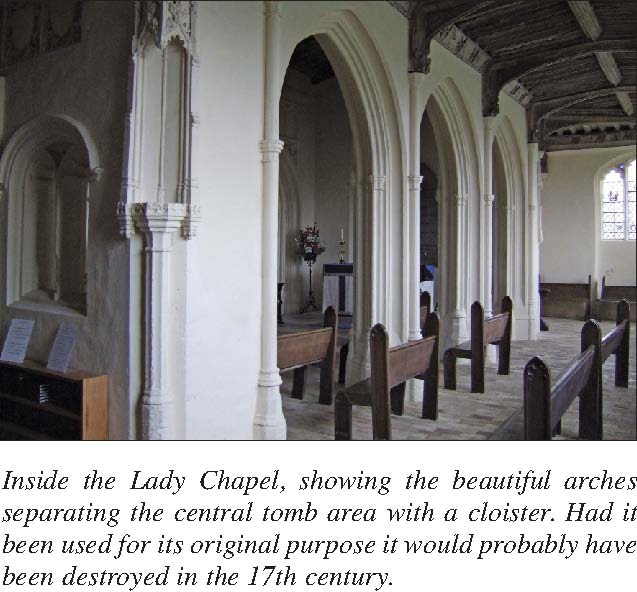

In 1984 I carried out a structural analysis of the church looking at it with fresh eyes in the hope of explaining some of the anomalies of which there are several. Chief among them was the design and purpose of this curious eastern extension. I was puzzled by the fact that several writers, including Pevsner, had commented on the fact that the external details bore little relationship to the interior, i.e. the triple gables and steep roofs which make nonsense of the very flat timbered roofs inside. Then there is the peculiar arrangement of a central shrine area surrounded by a “cloister thereabout”, to quote the founder; all very strange for a simple Lady Chapel. Finally, why is it detached from the main building? Nobody seemed bothered to reach an explanation.

Long Melford Through the Ages. Published 1986 E.A.M.

“…I will that when it liketh to God that my soul depart out of this world…there be made a chapel of Our Lady, well, fair and goodly built, within the middle of which chapel I will that my tomb be made…”

The Lady Chapel, originally conceived as John Clopton’s Chantry Chapel. Designed as a box within a box, the centre raised above the “cloister”. Converted for use as a school when the battlements were removed and gabled upper floor added in 1670.

These could so easily be the words of John Clopton who built this chapel but they are from the will of Richard Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, in 1439. He was buried in the chapel built in accordance to his will in the church of St. Mary in Warwick. It was ranked among the most splendid of the Chantry Chapels and has survived almost complete. Everything was done as he ordered. A great tomb of Purbeck Marble with angels and mourners along the sides under canopied niches similar to those, in the Clopton Chantry which are now empty. The Earls effigy lies on top, a living likeness because his surgeon helped and advised the sculptor. His eyes are open and they focus on a boss depicting Mary Queen of Heaven.

The whole of the Beauchamp Chapel was designed as a complete theological theme. Clopton knew that chapel. It was famous throughout the kingdom because the Earl was a national hero. John Vere, Earl of Oxford, was married to one of his descendants and acted as an executor for Clopton.

There can be no doubt that Clopton had set out to build his own version of that famous chantry. It explains the arrangement of a central shrine area for his tomb and the broad cloister surrounding it for the tombs of his descendants. In its original form the chapel had no gables; the roof of the shrine area was lit by a clerestory raised above the cloister. It was built off centre from the church so as not to obstruct the great east window of the chancel.

The central chapel has niches which may never have been filled because, although arrangements were made to complete the exterior after Clopton’s death in 1497 with battlements, we will never know what the interior theme of decoration was intended. In a codicil to his will in 1497 Clopton left instructions for 1200 marks to be released from his interest in Bower Hall, Pentlow, to be spent on the “garnishing of the Lady Chapel and the Cloister there about”.

The following text, in Latin, is carved on the north side of the chapel:

Let Christ be my witness that I have not exhibited these things in order that I may win praise, but that the Spirit may be remembered.

After completion, the chapel may never have been used because Clopton chose instead to be buried in the most coveted part of the church, to the left of the high altar where his tomb would be used as part of the great Easter festival. The extension to the Sanctuary shortly before his death made it possible. Piety overcame pride. To compare Clopton’s tomb with Cordell’s great Renaissance monument opposite can be very moving. They never knew each other and each contributed much to the Melford we know today.

As early as 1670, the Lady Chapel was in a ruinous condition and it was thought appropriate to convert it into a school. The battlements were removed and the gabled roofs were added to gain space for living accommodation, accessed via the vestry. It remained as such until the 19th century when the new schools were built at the foot of the green.

Sir William Cordell’s magnificent Renaissance style tomb faces Clopton’s across the sanctuary c.1582.

It was once again abandoned and used as a coal store. The Victorians, who were so often blamed for over restoration of our churches, restored dignity to the building but stopped short of removing gables.

I think it is a great shame that there is nothing to tell the visitor of the true nature of this most remarkable building. It would add so much to the appreciation of the history of the church and the true piety of Clopton.

On show in Melford Hall is a large survey map of the Manor, dated 1613. It shows in surprising detail the church at the top of The Green. There are no gables on the Lady Chapel.

It need hardly be said that Clopton’s home, Kentwell Hall, is within sight of the churchyard and well worth a visit. However, one gets to know the man better by visiting the North aisle of the church, which he built. In the windows are displayed, in 15th century stained glass, the portraits and the arms of many of his family connections. To the east of that aisle is the chapel his father built from which, through a little door, one enters the Little Chantry. Here you can sit quietly beside his tomb contemplating the nature of the man. Then visit the Lady Chapel and see it with new eyes.

Inside the Lady Chapel, showing the beautiful arches separating the central tomb area with a cloister. Had it been used for its original purpose it would probably have been destroyed in the 17th century.

On leaving the church, stand at the top of The Green and take in the full beauty of the Suffolk and Essex landscape that spreads into the distance. You will be within yards of another Roman road crossing The Green on its way to Clare and Wixoe. Along that road in August 1578 came the vast cavalcade of Queen Elizabeth with her escort of “200 young men clad in white and 300 of the graver sort in black” led by William Cordell, who was to entertain her at his great house. Much happened in that short stay, but that’s another story for another day.

Barry Wall

Barry Wall is a Historian. He founded the Sudbury History Society in 1999 and is currently Chairman. He has written books on Sudbury, the latest of which was published in 2004 titled “Sudbury – History and Guide” as well as a definitive history of Long Melford.