MINIATURE OR APPRENTICE PIECE?

I feel very lucky to have been involved in the art world for almost as long as I can remember. After a year in France, and having passed my secretarial exams, I spent nearly two years at the Bear Lane Gallery in Oxford, as secretary under the competent but formidable Elizabeth Deighton, who had the foresight to promote artists such as David Hockney, Frank Auerbach, John Piper, Patrick Heron, Ivon Hitchens and many more. It was an exciting time and I met them all – if only I had been able to save months, no years, of my £10 a week salary to buy a Hockney ‘Swimming Pool’ series or an Ivon Hitchens!

It is, I believe, rather appropriate that I should be writing for the Colne-Stour Magazine, because I have lived beside both these beautiful rivers. In 1965 I came to live at Hovis Mill, on the Colne between Sible and Castle Hedingham, and inherited this house, which my mother renamed Maplestead Mill, from her when she died in 1971. With it went the incumbent responsibility of maintaining the level of the river, and I remember many times in the middle of the night, in my nightie and in a storm, when I had to open the sluice gates to stop the river flooding. Of course, nowadays this job is undertaken by the Environment Agency. For the past sixteen years I have lived at Daws Hall on the Stour where, among many other things, I am a trustee and honorary treasurer of The Daws Hall Trust.

Having been on the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow at the ‘Miscellaneous’ table for the past 25 years, it is still not widely known that I particularly love pre-Victorian furniture. Apart from being surrounded by antiques as a child, my real appreciation of it began in 1966 when I joined Sotheby’s. Strangely, at that time, Sotheby’s considered any furniture after William IV (1837) was ‘too modern’ and was not included in their sales catalogues!

After my stint in Oxford it seemed only natural that the appropriate department at Sotheby’s should be pictures. However, getting in proved more difficult than a mere telephone call – the Personnel Director told me there was no vacancy but that he would call me if and when one turned up. I didn’t wait for his call but kept ringing him each week, so that he finally said ‘you’d better come and see me’.

Before the interview, he kept me waiting well over an hour in his secretary’s office, during which time I could not help but overhear her talking on the telephone about when she was leaving. So when he finally called me in and told me once again there was no vacancy, I suggested he employ me as his secretary! He must have been reasonably impressed because he rang me a few days later and offered me a position on the reception counter.

In the 1960s the reception counter was the main area for all valuations, and for me it was fascinating to see all manner of odd, famous and beautiful people either buying catalogues or bringing in their possessions, which were valued there and then at the counter by the relevant expert. I always say that the best way to learn about antiques is ‘hands on’.

I well remember some of the people who came to the counter: Tito Gobbi, Maria Callas with Aristotle Onassis, Henry Moore, Francis Bacon, David Attenborough (who still collects fossils), the King of Sweden, the film director Cubby Broccoli, Stewart Granger (my uncle) with Jean Simmons, Ava Gardner, to name but a few. Then there were the odd-bods, many of whom would set me giggling so much that I had to get a colleague to take over.

From the main counter I did a stint in the Silver Department under the charismatic and charming Richard Came, but silver to me is not a tactile medium; at least it didn’t appeal to my aesthetic sense, so when an opening appeared in the Furniture Department I grabbed it.

Although it was called the ‘Furniture Department’, in the 1960s, clocks, carpets, works of art, automata and dolls all came under its remit. Although I learned a lot about furniture, the idea of a woman valuing a tallboy in some stately home was inconceivable, so I became more and more involved with the dolls and automata. But I’m straying from the subject of this article…

Strangely, even today, there is no definitive literature on miniature furniture, only on ‘nursery’ furniture, and in Thomas Chippendale’s published drawings there are no designs for children’s furniture.

Antique miniature furniture tends to be more difficult to find than children’s furniture. It is often impossible to tell the difference between an ‘apprentice or cabinet maker’s sample’ and a child’s piece; it entirely depends on the quality, not only of the type of wood used but the intricacy, joining and overall finish. ‘Nursery’ furniture can be as accurate and precise as a sample of the adult design.

Equally, there is some exquisite dolls’ house furniture, truly Lilliputian, so precise and to scale, which could well have been made by Chippendale and other famous cabinet makers over the centuries. I have huge respect for those men and women today, who spend hundreds of hours making dolls’ house furniture. Their patience must be limitless and their attention to detail a true labour of love.

My own collection of ‘small’ furniture was probably kick- started by the grandfather I never knew. He was rector (as were his ancestors before him going back two centuries) of Walton-on-Trent church. Apart from being a competent watercolourist, he carved all the pews and rood screen in the church, and (Fig. 1) shows the little child’s chair he lovingly carved and which I inherited when my father died. Its value is very little, but to me it is very special.

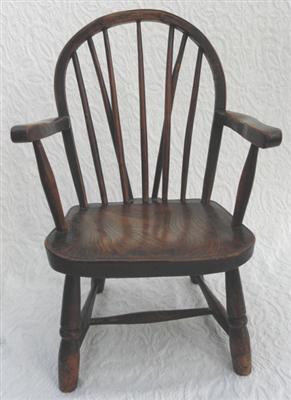

Together with the little chair made by my grandfather, I also inherited (Fig. 2) the little spindle-back Windsor armchair made of beech with an elm seat, circa 1770; this could very well have been an apprentice piece or cabinet- maker’s sample, although it is simple in design.

In an extract from The English Chair by M. Harris & Sons of 1937 is the following:

‘No-one knows why or when a beech chair with an elm seat came to be called a ‘Windsor’ chair. Presumably a chair-maker evolved the type in Windsor Great Forest, and the name stuck. An advertisement of April 1730 speaks of “all sorts of Windsor Garden Chairs, of all sizes, painted green or in the wood, at John Brown’s, at the Three Chairs and Walnut Tree in St. Paul’s Church Yard, near the School”. It seems to prove that the product it described was only suitable for rough usage.

‘Whatever the truth about the origins of the Windsor chair, even as late as 1937 in the woods near High Wycombe there were chair-makers, known locally as ‘bodgers’ who, as Sir Lawrence Weaver wrote in 1929, “buy trees as they grow, saw the trunks by hand into lengths suitable for the leg of a chair, split those great sections with an axe wielded with primeval skill, and then turn the leg of the chair on the spot, in the open air, with a pole-lathe so simple that it might have made the balusters of the Ark” (extract from The English Chair).’

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

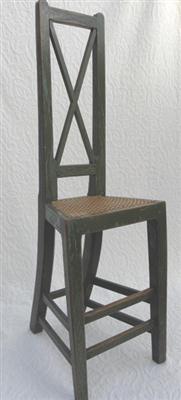

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

The ‘Windsor’ chair is by no means an exclusive product of the English countryside. It has been a familiar and popular type in America from about 1725, where it has evolved on far superior lines in the eyes of American collectors. There are very few English Windsors on the other side of the Atlantic. The Americans only imported fine furniture, in which category they did not include the English Windsor, which they considered to be lacking in finesse and grace.

Fig. 3) This is a Regency child’s green painted deportment or posture chair, circa 1815. Similar chairs were made to the specification of the famous surgeon and anatomist Sir Astley Paston Cooper who died in 1841. Just imagine trying to make a child sit in this today: they would probably ring ‘Childline’!

My most prized miniature chair (Figs. 4/5) is a Louis XV walnut ‘menuisier’s’ or apprentice piece, circa 1760. The close-up shows the fine carving, and I am still searching for the right petit-point upholstery for it. This is a rare piece.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 8.

Miniature Tables: My criteria for small furniture is that it should be useful, apart from looking attractive. (Fig. 6) is one of my little tables which I bought at auction on the telephone without previously viewing it. I had obviously not taken in the size, mixing inches with centimetres, so that when my colleague on the Antiques Roadshow, Clive Stewart-Lockhart (who is a Director of Dreweatt Neate Auctioneers), brought it to me, I had to laugh as the measurements in the catalogue were obviously correct, 12cm high by 22cm wide by 12cm deep, not inches! It is

Fig. 6.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 10. enchanting and I love it; it is 18th Century and carved oak, but I doubt an apprentice piece, more likely for a large dolls’ house.

Chests and desks: These are so very useful for storing small things such as jewellery, buttons and sewing accessories, apart from being most attractive. The elm chest (Fig. 11) is a fairly large size, with three graduated long drawers, 19th Century and with ivory escutcheons, 15in high and wide, likely to be a sample or a child’s bedroom piece as it is simple in design (Courtesy Mark Dawson).

The small mahogany chest (Fig. 12) has four graduated drawers and elaborate brass escutcheons, which seem far too large and indeed are probably the prototype for the full-size version. Under the base of the third drawer there is a handwritten inscription ‘Mary Scutcheon given to her by Mrs Cooper in the 11th year of her age (June 21 1834)’, although its manufacture is earlier, George III circa 1780. If the lining of the drawers and the back of a piece is oak rather than pine, which it is in this case, then it is of superior quality, so it was a lovely 11th birthday present!

The next table (Figs. 7/8) is a little larger, 26cm diameter and 24cm high, with a tilt top on a baluster stem and tripod base on little gilt claw feet, mahogany and Victorian, probably a sample for the full size (Note the intricate metal mechanism for closing and opening). The last table (Figs. 9/10) is smaller at 61/2in high, top 93/4in by 75/8in; a little octagonal tilt-top example, the wooden closing lever basic and not substantial enough or suitable for a full size table, so not a sample.

Fig. 11

Fig. 12

A later, but nevertheless elaborate and beautifully made piece, is (Figs.13/14) a French menuisier’s commode in the style of Louis XV, early 20th Century, the parquetry on the top and fall front is of sycamore, palissander and rosewood with satinwood stringing. The central lozenge on the front depicts La Fontaine’s Le Loup et l’Agneau. When open there are two short and one long drawer veneered in palissander and satinwood. A showy piece, lovely honey colour and in excellent condition, size 111/2in high, 143/4in wide, 91/4in deep.

Fig. 13.

Fig. 14.

The following four bureaux all vary in date and quality, although on first sight they appear very similar. All would have been cabinet makers’ samples, all roughly the same size, 9 – 91/2in high and wide and 4 – 41/4in deep, all veneered in walnut with holly stringing, fall fronts revealing stepped interiors, pigeon-holes, all including a ‘secret’ well.

The two earliest bureaux are (Figs. 15/16) the drawer linings and back are oak, their escutcheons of early form, both circa 1700-1720. (Fig. 17) has later escutcheons, circa 1740, also oak back and drawer linings, and (Fig. 19) has a pine back and drawer linings which make it much lighter than the others and of less superior quality, although it is still mid-18th Century.

Figs. 15 and 16.

Inside of Figs 15 and 16.

Figs. 17 and 18.

Inside of Figs. 17 and 18.

The rarity of well made miniature period pieces has put them into the same price range as the full size furniture. So, small only has meaning in size, not value, and with more and more people down-sizing, perhaps it makes sense to look out for the real thing, but in miniature!

Bunny Grahame

Since 1988 Bunny has been running her own consultancy business Campione Fine Art engaged in valuing, buying and selling all forms of antiques on behalf of clients.

She particularly enjoys taking charity auctions, and frequently lectures on antiques and gives talks about her experiences ‘On and Off the Antiques Roadshow’. Bunny speaks French, Italian and a little Greek. Her hobbies include painting, bee-keeping, bridge, tennis, riding, skiing, salmon fishing, bird watching, cooking, classical music and opera. She has two sons, two grandsons and five step-grandchildren.