A National Centre for Gainsborough set within the town where he was born and the landscape that inspired him

2018 is the diamond jubilee of Gainsborough’s House and marks sixty years since the purchase of Thomas Gainsborough’s family home by a group of local and national supporters, creating an extraordinary legacy that is now on the brink of becoming a national centre for the artist.

Front view of Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury.

In 1956, a house in the market town of Sudbury was advertised for sale in Country Life. Of late medieval origins, it had, like many other houses in the town, been developed in the Georgian period and given an elegant street façade. What distinguished it was that it had been the home of Thomas Gainsborough in his youth. A group of local supporters, including Sir Alfred Munnings, inspired by a recent campaign to save Renoir’s House at Cagnes-sur-Mer, got together and raised the funds to acquire the house; it was then opened to the public in 1961. Since then it has flourished as a museum dedicated to the artist, opening seven days a week, mounting temporary exhibitions and gradually acquiring a significant collection of paintings, drawings and prints by Gainsborough, as well as a large archive of material relating to the artist.

Back view of Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury.

In September 2016, Gainsborough’s House was awarded a stage 1 pass from the Heritage Lottery Fund for a project that could radically transform its future. In recent years, funding has been in short supply for many regional museums and galleries. From 2011 to 2013 the House had to operate without a Director and other core staff, but, over the last three years, this situation has been reversed. Staff numbers have doubled, the programme of events has been far more ambitious, and this year the House achieved the highest visitor numbers in its history for the fifth year in succession.

Panoramic view from proposed new galleries at Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury.

The Vision

Reviving an Artist’s Birthplace: A National Centre for Thomas Gainsborough is a plan to redevelop Gainsborough’s House and convert the building and land, recently acquired by Babergh District Council, at the back of the House. The aim is to radically improve how we present Gainsborough, through a gain of four new display areas, as well as a designated space for larger temporary exhibitions. This will benefit not only Gainsborough’s House, but also the town and the region.

Perspective section of proposed new galleries at Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury.

House-museums devoted to individuals offer insights into the character and interests of the artist, writer or musician and can also examine the age in which they lived. The aim is to keep a balance between the two. The way in which this will be achieved at Sudbury is by converting the newly acquired building into a landmark gallery. Gainsborough’s art can then be shown in a purpose-built gallery environment. This would leave the House free to explore the artist’s life and character, and the period in which he lived. It will enable the House to present recently discovered material concerning hitherto-unknown aspects of Gainsborough’s life and background, while the new gallery will have the space to accommodate large-scale works and full-length portraits. Visitors, therefore, will be able to see a greater range of the artist’s achievements before entering Gainsborough’s House, which will provide a context for his art.

The development of the historic house is an important element of the project and this essays considers two further key themes, which form the backbone of the redisplay.

Early Gainsborough and the Creative Process

Gainsborough (1727-1788), Tomas Abel Moysey (1743-1831) 1771. Oil on canvas. On loan from a private collection. Gainsborough’s House.

Gainsborough was baptised at the Independent Meeting-House on Friar’s Street, Sudbury on 14 May, 1727, born into a weaving family that was predominantly dissenting. His mother was from an Anglican family, and it is generally thought that she was ‘a women of cultivation, and an amateur painter.’

Given Gainsborough’s natural instinct for landscape painting, it is perhaps not so surprising that Gainsborough was born into the rural market town of Sudbury in Suffolk, surrounded by countryside, which still evoke his paintings and drawings. Yet it was not just his mother’s side of the family that gave Gainsborough opportunities to develop his natural talent, and his namesake and dissenting uncle on his father’s side represented the wealthier side of the family. They could afford to commission John Theodore Heins (1697–1756) to paint all their immediate family with individual portraits in 1731 as well as bailing out Gainsborough’s father when he went bankrupt in 1733. The paintings by Heins must have been amongst some of the first paintings that Gainsborough would have seen at first hand.

Philip Thicknesse, Gainsborough’s first biographer, who published his anecdotal sixty-one page booklet within months of the artist’s death recalled ‘that there was not a Picturesque clump of Trees, nor even a single Tree of beauty, nor hedgerow, stone, or post, at the corner of the Lanes, for some miles round about the place of his nativity, that he had not so perfectly in his mind’s eye, that… he could have perfectly delineated.’ Thicknesse was not alone in emphasising the inspiration of nature to Gainsborough. Sir Henry Bate Dudley (1745–1824), one of Gainsborough’s great supporters, wrote in his obituary of the artist, ‘That nature was his teacher and the woods of Suffolk his academy’. Sir Joshua Reynolds in his eulogistic Academy Discourse, which followed Gainsborough’s death, noted that his landscapes were ‘a portrait-like representation of nature, such as we see in the works of Rubens, Ruysdaal, and others of those schools.’

The idea of Gainsborough as an entirely natural and self-taught artist was prevalent in the late eighteenth century. Yet this is misleading, for even though he was possessed with a great deal of natural talent, training was undoubtedly necessary. Nature is a mass of fragmented colour, shade and forms, whereas a painting is a cohesive and harmonious whole. Only by studying the work of other artists, being trained by them, will enthusiastic observation of nature be translated into a successful and sophisticated painting.

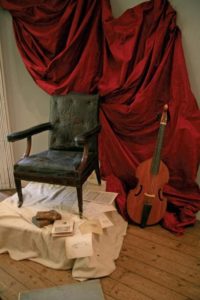

With the encouragement of the Paul Mellon Centre, Gainsborough’s House developed a project called The Painting Room. This culminated in a two-day symposium, one day held in London and the second in Sudbury; and in a temporary exhibition co-curated with Giles Waterfield, in which we gathered together objects, such as Reynolds’s easel and sitters’ chair (loaned by the Royal Academy, London), as well as paint bladders, an écorché and a bust of blind Homer that would have been used in a Georgian studio. We even created a mock-up of what such a room might have looked like.

With the encouragement of the Paul Mellon Centre, Gainsborough’s House developed a project called The Painting Room. This culminated in a two-day symposium, one day held in London and the second in Sudbury; and in a temporary exhibition co-curated with Giles Waterfield, in which we gathered together objects, such as Reynolds’s easel and sitters’ chair (loaned by the Royal Academy, London), as well as paint bladders, an écorché and a bust of blind Homer that would have been used in a Georgian studio. We even created a mock-up of what such a room might have looked like.  This proved a useful exercise, helping us gain ideas as to how we might order the display of our rooms in the future. In the House, wall texts and labels will be used, but with discretion: there is always the danger of being visually intrusive and breaking the spell that can be evoked by sensitive historic re-creation.

This proved a useful exercise, helping us gain ideas as to how we might order the display of our rooms in the future. In the House, wall texts and labels will be used, but with discretion: there is always the danger of being visually intrusive and breaking the spell that can be evoked by sensitive historic re-creation.

Detail of the Gainsborough in His Own Words exhibition, RijksMuseum Twenthe, Netherlands 2016.

While pursuing these ideas for future displays, Gainsborough’s House developed an important partnership with the Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede, Holland. This was the first regional Dutch museum to acquire a Gainsborough painting and its curators were keen to mount, with our help, the exhibition at Enschede, Gainsborough in His own Words (2016), which set out to interpret his art, with the help of some of Gainsborough’s letters, to a Dutch public unfamiliar with his work. Voted one of the top five exhibitions in Holland in 2016 offered valuable lessons for Gainsborough’s House. We lent a large number of paintings, drawings and contextual material to Holland, and, in return, Gainsborough’s House borrowed from the Rijksmuseum Twenthe nine seventeenth-century Dutch landscapes from its golden age, including works by Jan van Goyen, Salomon van Ruysdael and Aert van der Neer. The fact that Dutch landscapes of this kind had a crucial influence on Gainsborough’s early development made their presence in Sudbury a moment of real importance to the House.

The Challenge

The challenge is to evoke the spirit of an artist, without the House becoming a static shrine or losing its sense of authenticity. Evocations of the past are attractive to visitors, but, as in the case with Gainsborough’s House, not many objects original to the Georgian period remain; and questions of security, as well as environmental concerns, can make it difficult to display objects as they would have been seen when the artist was alive. Should more ephemeral effects be recreated? There are house-museums where this has been done well, as at Charleston, the former home of certain members of the Bloomsbury group, where the visitor gains the sense that the room is still in use and its residents are merely temporarily absent. But all too often in house-museums it is necessary to employ minor interventions around individual objects for security reasons, which, however discreet, can alter their context and the experience offered to the visitor.

Gainsborough’s House is fortunate to have not only the house where the artist lived, but also his garden with its ancient mulberry tree. In Sudbury, we are also surrounded by the landscape Gainsborough loved, the ‘Picturesque clump of Trees…’ that Thicknesse recalled. This reminds us that, although art is often today shown within a vacuum or white space, it certainly was not created in one.

Detail of Creating a National Centre for Gainsborough exhibition 2017, Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury

It is to be hoped that developing Gainsborough’s House into a national centre for the artist, and providing a major gallery for the region, will help to spearhead the redevelopment of this historic market town. Local pride and a centre that focuses on one of Britain’s greatest artists can encourage cultural tourism. Gainsborough’s House is grateful to all those trusts, funds and individuals who have supported its work so far. The artist himself once wrote: ‘What will become of me time must show; I can only say that my present situation with regard to encouragement is all that heart can wish but as all worldly success is precarious I don’t build happiness, or the expectation of it, upon present appearances. I have built upon sandy foundations all my life long’. Yet since his death in 1788 his reputation has remained consistently and deservedly high and at Gainsborough’s House we are able to build upon this firm foundation.

Cedric Morris

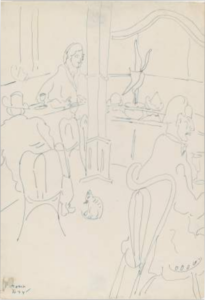

Cafe du Dome 1924, Cedric Morris.

One of the strongest themes of the redeveloped Gainsborough’s House is Suffolk artists. The new displays will explore the complex relationship between the extraordinary landscape of the region and the artists that it inspired. It is particularly exciting for us to receive a bequest of works from the studio of Sir Cedric Lockwood Morris (1889–1982), which represents a significant acquisition to our collection. Morris met the painter Arthur Lett- Haines (1894–1978) in 1918, and lived with him for the following sixty years, first in Paris and London in the 1920s before moving to Suffolk. In 1937, they founded the East Anglian School of Painting and Drawing in Dedham, Essex, with Morris as principal. Three years later the school moved to Benton End, Hadleigh, Suffolk, where they lived the rest of their lives. Whilst there they taught many students including Maggi Hambling and Lucian Freud.

The gift from Maggi Hambling and Robert Davey amounts to over 100 landscapes and portraits, which include 46 oil paintings and 58 works on paper. We are enormously grateful for the gift, which means that the legacy of Cedric Morris has a home in Suffolk that can be seen by all.

The exhibition, Cedric Morris at Gainsborough’s House, drawn from the collection and selected by his pupil Maggi Hambling is on between 10 February and 17 June 2018.

Mark Bills

Mark Bills studied at The Slade School of Art and at Birmingham and Manchester Universities. He is currently Executive Director of Gainsborough’s House. He has been very closely involved in the project to build a new gallery, behind the house, and raising the necessary funding. He has written several books and numerous articles about 18th and 19th century art.