THE PAINTED CHURCH BECOMES BURY’S CATHEDRAL

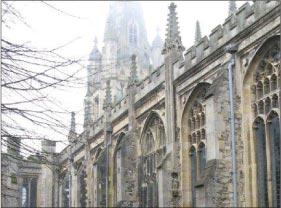

St James’ Church today.

St James’ Church by Henry Ladbrooke.

One of the lesser known features of the Norwich School painters was their interest in travelling the length and breadth of East Anglia in search of subjects. This was not only for their desires but also for their clients. After the big city of Norwich, Yarmouth became their next town of choice in which to settle, with its vibrant coastal and fishing scenes that were to fill so many canvases. John Sell Cotman, the great Norwich School watercolourist, lived there for many years; and John Berney Crome, son of the famous John Crome, fled there when bankrupted. Quite surprisingly, it’s only recently been realised, that their third choice of town was Bury St Edmunds. Primarily, it would have been Bury’s ancient buildings, with its abbey ruins, which provided the picturesque attraction. It must also have appealed as a pleasant place to dwell and work in.

Now is the moment to introduce the fascination that several artists had with church buildings. Robert Ladbrooke, who had founded the Norwich School with Crome in 1803, set out in the 1820s to draw all the rural churches of Norfolk, aided by his son John Berney. Over ten years later they published nearly seven hundred church lithographic plates (many of these churches exhibit their own examples today, culled from the volumes of the books published). Robert’s eldest son, Henry, born in 1800, decided to enter the church and then changed his mind. He, too, got the bug for painting landscapes with churches or even, better still, Norwich Cathedral. In 1823 he made his name in the Norfolk press with the magnificent scene from Mousehold Heath of the City of Norwich centred on The Painted Church becomes Bury’s Cathedral this building. Around 1830, John Berney Crome, Henry’s cousin, visited Bury to paint the old abbey ruins, a version of which is housed in the Norwich Castle Museum. Perhaps encouraged by this endeavour, Henry did likewise and may first have chosen to paint the distant view he saw (or invented) on his approach over high ground; he portrayed the old abbey and churches and even the dome of Ickworth Hall on the far horizon. Then, in the early 1840s, two of Henry’s brothers, another ‘Robert’ and Frederick, moved into the town.

The Ladbrooke family members all taught people to draw and paint and, perhaps for this reason, Henry moved into virgin territory away from his brothers and settled in Kings Lynn in 1847 for twenty years. He used to visit Cambridge regularly for a period to teach an undergraduate. Arriving one day, he found a note pinned to the student’s door: ‘Sorry, gone hunting, you will find luncheon on the table’. So that source of income, it seems, was not very reliable. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that he should continue his way to Bury to see his brothers and seek work.

Before the Manor House Museum, once the town home of the Bristols, was closed down, a striking painting of St James’ Church and the Great Churchyard and Norman Tower could be seen hanging next to the entrance hall. It was described as being by the architectural artist, Richard Bankes Harraden a contemporary, who lived in Cambridge and is known for his college views. Whoever informed the museum of this attribution knew little, if anything it seems, of the Ladbrooke family’s association with the town.

The painting had been acquired, or commissioned by, the Gage family who lived at nearby Hengrave Hall, where it hung until put up for sale in 1952. So, purchased as a piece of town history by the museum, it soon found pride of place upon its walls. The church is painted pretty much as it had been built by one of the greatest English masons, John Wastell of Bury St Edmunds, in the early 1500s. However, in 1777, the original very low pitched roof over the nave, then lined with ornately panelled timber, was replaced by a new one of deal. This was removed and replaced a second time, in 1864, by a steeply pitched roof erected on an entirely new hammer-beam structure. It is said this bold construction, featuring painted angels, was built to emulate the finer roof of St Mary’s next door. The rest is history: in 1914 the church became the cathedral of the newly created Diocese of St Edmundsbury and Ipswich. A close look at this oil painting reveals the characteristic handling of foliage belonging to none other than Henry Ladbrooke; a late painting of his suggesting it was done no earlier than the 1860s. The colours of the masonry, the pathway and the sky all relate to Henry and are distinct from those used by RB Harraden. Henry used the frond-like effect of drooping branches at that time of his life (difficult to pick out in the small illustration) – today limes still line the churchyard avenues. The curious building on the right side, Samsons Hall, is part of the old abbey but stripped of its facing stone. So, was the painting commissioned by the Gage family, who knew the church was going to be disfigured by having its roof removed in 1864, or was there another possibility? By 1865, incidentally, the Ladbrooke association with the town had ceased upon the death of Frederick, with Henry having little reason to visit thereafter. Henry himself was shortly to return to Norwich, where he died in 1869.

John Wastell, the famous mason who helped build Kings College Chapel, also had a hand in Hengrave Hall, in which he had built an oriole window and similar fan vaulting in the great hall ceiling. Maybe the Gages wanted to display another exhibit of Wastell’s handiwork, for his services were employed abundantly. He supervised the rebuilding of the nave and aisles of elegant St Mary’s Church, Saffron Walden, in the

perpendicular style of the period. It is mooted he had a part in work on Dedham and Lavenham churches. He is famous, further afield, for the building of the cross tower at Canterbury Cathedral, one of the great works of the perpendicular, known as Bell Harry.

Upon closure of the museum, the Henry Ladbrooke picture was removed for storage to West Stow. It would be a nice surprise if it could be rehung one day in the Guildhall, the oldest civic building in England, which is to undergo refurbishment. Another of his large paintings, which is sadly no longer accounted for, is that of the Abbott’s Bridge over the River Lark on the other side of the abbey grounds. However, another Norwich School artist, who moved to Cambridge in 1854, has obliged with his own identical view. This shows the black poplar tree overhanging the water and bridge, as it still does today, though now older and larger, with its weeping branches. The inn, still standing, was close to the old East Gate. These were the essential ingredients of Henry’s oil too. The smaller painting illustrated is by Samuel David Colkett; he has managed to add St Mary’s church in the distance with St James hidden. In the V&A there is also a fine watercolour by Michael Angelo Rooker of the west end of St James’ church, at the end of the eighteenth century, showing the softness of its low roofline held by gently matching triangular stone framework, which many may have been sad to see so altered.

Thus, with fresh research, more entwined history emerges about an accomplished painter of the Norwich School, a great English architect and an old Suffolk family, not to mention a cathedral, all woven together by its many connections. Henry’s painting is the best I have seen of the original church and represents a potent record of just how Bury St Edmunds’ Cathedral, like a slowly hatching chrysalis, has emerged from the confines of a pretty 16th century parish church. Finally, the transformation is complete.

Peter Kennedy Scott

This is the third article Peter has written for CSCA Magazine. His knowledge of the Norwich School is encyclopaedic and his definitive book on the subject is awaited. He is in demand for lectures, and the cataloguing of pictures by the well-known auction houses.

St Mary’s, Saffron Walden.

Abbotts Bridge by Samuel David Colkett.