A Pint of Port to Paint a Picture

A Portrait of Edwin Cooper

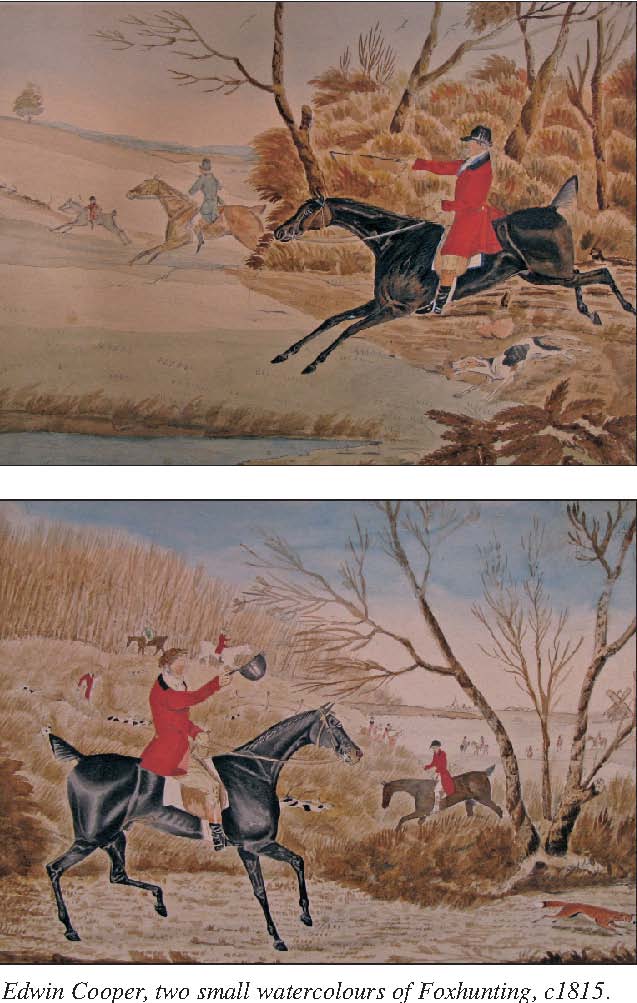

The present set-back to traditional hunting gives us good reason to look at the achievements of one of our few East Anglian animal painters. In his time Edwin Cooper acquired considerable distinction by recording many scenes in the countryside, scenes now forbidden and lost to us. He gained numbers of commissions to paint horses, hounds and hunts, and ended his artistic life a prominent member of the Norwich School’s finest group of forty painters. One of the last events the Norwich Society of Artists mounted was a memorial exhibition of Edwin Cooper’s work in 1833, shortly following his death and only months before the Society disbanded after thirty years of promoting paintings in Norwich. This was to seal Cooper’s status for ever.

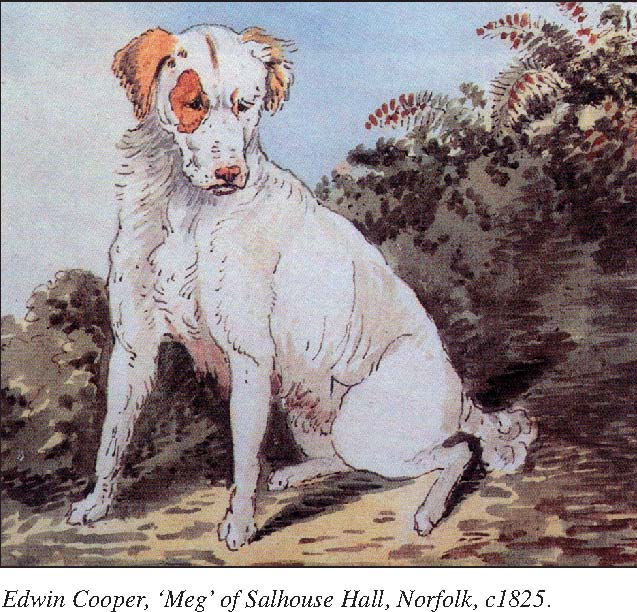

Edwin was born in Bury St Edmunds in 1785, the son of a drawing master at the grammar school. His father was a miniature portrait painter. But from the start Edwin’s brush was attracted to painting animals and local pets.

The earliest painting discovered so far, dated 1801, is a small watercolour of cats and dogs, with a terrier called Marquis, belonging to the vicar of nearby Stanton. His first major commission was an oil painting of Lord Grosvenor’s horse, Enterprise, winning the Brightelmstone (Brighton) races in 1804. It is likely he met and learnt with the horse painter, Ben Marshall, at Newmarket, where they both stayed during the racing season. Cooper’s next step was to exhibit with the Norwich Society in 1806, as a ‘horse portrait painter’. His quest had begun in earnest; he now began to chase hither and thither over Norfolk and Suffolk and elsewhere to become the animal painter of the Norwich School. Eventually he would leave a fine legacy to hunting, and husbandry, in scenes so often familiar to the folk who cared for the countryside – and so true to life that you can almost hear the horn blow when you spot one.

He is known, by reputation, as ‘Cooper of Beccles’, denoting the town where he spent the second half of his life. Yarmouth and Beccles race courses were known to attract him, along with a bit of gambling too, but never so much as the fox hunting fields bordering the Waveney Valley. The thought of a drop of booze may never have been far from his thoughts (he was often commissioned to paint pub signs) or, for that matter, from those of his subjects too. A bottle of port was a requisite on an unknown number of occasions before his brush was ready to be wetted. Likewise his subjects, elegant huntsmen, also looked forward to a noggin of stirrup cup, before they too were ready to be propelled across fields at flying speed. For their numbers, often large, if a tray were not to hand at a country house meet, it was only too easy to pull an oil panel of a rusty old relative off a wall on which to pass the punch around.

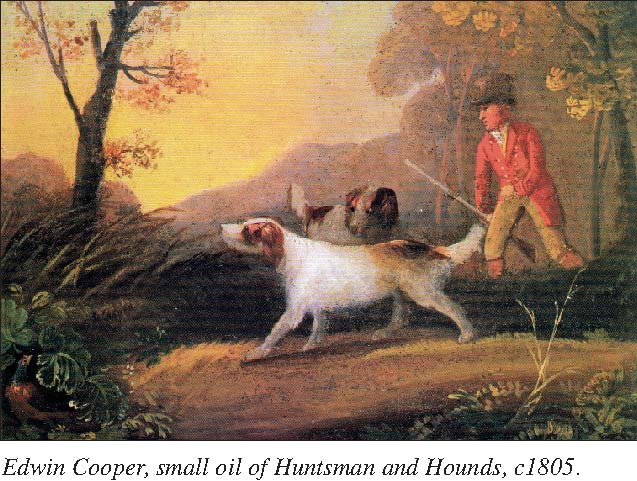

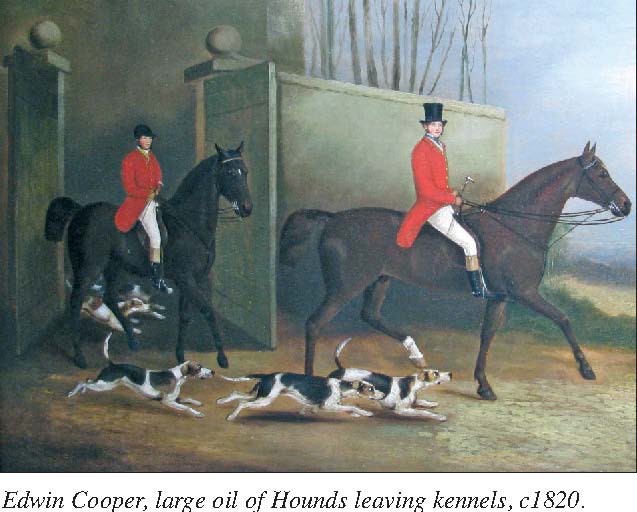

As a painting subject, hunting foxes, considered evil vermin and the number one enemy, was a popular one. Shooting game, which was prolific in those days, was another sport often captured on canvas. It was nothing on a big estate to bag a thousand hares, even two thousand. Cooper however preferred painting the single game keeper, gun under arm, patrolling his beat. Cooper thrived at a time when other better known sporting artists like Henry Alken and JF Herring were at work. Sometimes he chose to paint a coach and horses, perhaps inspired by Cooper Henderson’s stagecoaches at the gallop – a feature on the newly laid firmer roads. These were invented by Macadam in 1818 and spread themselves gradually over the country – more speed could mean breakfast in Norwich and dinner in London. There may have been an element of self indulgence with his own popularity for Cooper’s face (judging from a self portrait) can be seen aloft several horses. And to add to that he is seen to sport pink, probably painting himself as illustrated in the fine oil of hounds leaving kennels, still in its period frame almost certainly of Norwich origin. Just as Stubbs studied anatomy, so Cooper pencilled away at horses – there is a collection of drawings in the Norwich Castle Museum along with the self portrait. Cartoons were the order of the day too, led by Thomas Rowlandson. Cooper obliged with devils, runaway horses and stricken riders, and overladen wagons and nags grinding to a halt. He signed and dated many of his works, or at least one of a pair – he was often asked to do two or more scenes of the hunt – but sometimes owners, it seems, may have decided to obliterate his name. Done, it must be guessed, in the hope that guests to their mansions might be persuaded the fashionable oils were by more famous names, like Ferneley, with consequent flattery and back-slapping for the host: ‘we will drink to that’!

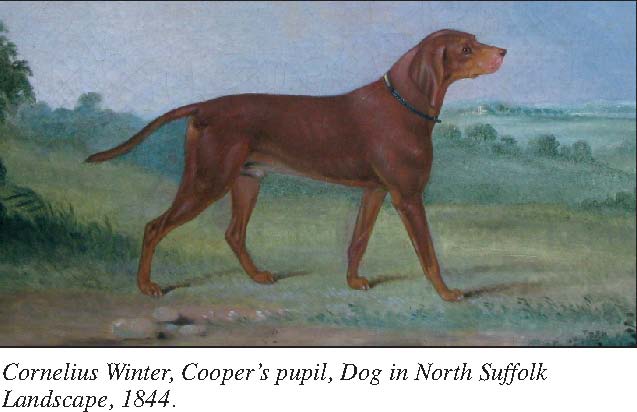

Not only was Cooper a locally established name amongst the landed gentry here, Lords Hastings and Henniker and the Gooch family of Benacre had collections, but also among landowners afar who collected sporting prints. Ackermanns in London owned the ‘Eclipse Sporting Gallery’ in Regents Street and published Cooper’s prints of race horses and lithographs of cock fighting – in those days a well recognised sport. Today Cooper’s works are spread far and wide. His horse portraits can be found in the library of Calke Abbey (the owner had a relation living at Harleston in Suffolk for whom these were painted). The oil of hounds, mentioned above, bears an old label with Lord Bruntisfield’s name – his family is a Scottish one. Cooper was by no means as prolific a painter as other equestrian names of the day. There is evidence that he spent time teaching pupils, like other Norwich artists so often did, which could curb output – as happened in the case of John Crome, founder of the Norwich School. Cooper’s best known pupil was Cornelius Winter, who lived at Bungay and painted animals against backdrops of the ‘Saints’ country, south of the town, so called because many such dedicated churches stand out in isolation on a level landscape once ravaged by the Black Death. On his own death a large collection of Cooper’s drawings, no doubt used as working models, was discovered amongst Winter’s possessions.

Only in his latter days, quite probably, did the story about a bottle of port become something of a legend. Possibly with the gentle help of its potent properties, not to mention a few good dinners in country mansions where he was a popular raconteur, he passed on aged forty-six when, apparently, still in his prime. The Sporting Magazine described his abilities thus: ‘the powers and symmetry of the horse and the instinct of the dog are everywhere preserved with animation.’ The Bury Free Press described Cooper in an obituary as ‘the Morland of his day’. So an era ended for an artist who loved to paint horses and whose owners loved the work Cooper gave them. Nobody else, in these parts, had electrified the hunt at full tilt as Cooper had managed, with or without a tipple or two. Finally, it is worth reminding ourselves of a small and special local exhibition that was held in 1985 to celebrate the life and times of Edwin Cooper – at nearby Gainsborough’s House. Indeed, we can justly lay claim to the fact that he was our very own East Anglian painter of horse and hounds, and the history of fox hunting, two centuries ago.

Peter Kennedy Scott

Peter continues to be asked to attribute and value paintings of the Norwich School, for the major Auction Houses. He is in the middle of writing a definitive book on The Norwich School of Painters.