Squash a Squirrel – Save a Tree

The Menace of Bark Stripping.

Some 60 years ago, 1932 to be precise, a bounty was introduced in the UK to try to deal with the grey squirrel invasion. The bounty was paid at the rate of 6 pence per tail, and increased over the years to 2 shillings, continuing in one form or another until 1957 when it was abolished. Even in those days it didn’t, as I remember, provide much of an economic incentive to a small boy with an airgun. There were much better pickings to be had from shooting rabbits.

The grey squirrel, as everyone knows, is an alien introduction from North America. The direst predictions about the effect of the greys on our native British habitat have all come true. The greys have, in most parts of the country, driven out the reds, a smaller, gentler, prettier, harmless species. The greys have also decimated much of the UK’s young forestry and have done considerable damage to our woodland birdlife.

Meanwhile, the reds hang on only in the Isle of Wight, Anglesey and the North of Scotland; their existence threatened not just by competition for food from the greys but also by the squirrel pox virus which is carried by the greys but, typical of this unjust world, kills the reds.

So, what has anyone done about it? The bounty arrangements have been dismantled, the furry animal brigade are in the ascendant, and you can be arrested if your dog so much as takes a sideways look at a squirrel in Hyde Park. In fairly recent times the Esme Kirby Trust offered a bounty of £1 a tail as part of the Anglesey red squirrel project and met with predictably vociferous opposition. A spokesman for the North Wales Wildlife Trust is quoted as saying “We are afraid people will kill, trap and shoot squirrels just for the money”. If only…….

Peyton Hall 2008. Acer Capadoccicum Rubrum completely stripped. Tree already dead and cut down.

Although most people probably have some idea that grey squirrels are displacing the reds, those who are stridently anti-culling, invariably fail to mention bark stripping and the huge threat posed by grey squirrels to woodland conservation. Even the majority of country people do not seem to recognize the signs of squirrel damage, and are unlikely to have witnessed at first hand damage done by squirrels in young plantations. Until recently, I was one of them. Although aware of the threat, I had shoved it to the back of my mind and, as a compulsive tree planter, had carried on regardless.

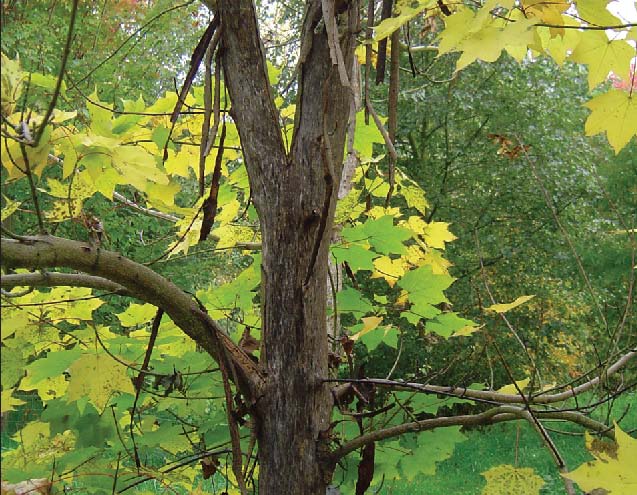

About 20 years ago, I put in a number of small grant-aided plantations devoted to English hardwoods and as these reached the age of about 15, I began to notice missing patches of bark, particularly on field maples. Initially I put this down to deer of which we have a lot, but it didn’t take me all that long to realise that many of the missing patches of bark were half way up the trees and that none of the species of deer to which we play host are much good at tree climbing. The miscreants could only be grey squirrels. My view at the time was that I just had to put up with it, but then 2 years ago damage began on a much bigger scale. Almost overnight, the majority of our young hornbeams – my favourite English hardwood species, were stripped naked. In some cases, trees of 18ft or so were left without a vestige of bark even down to the smallest branches. The damage to field maples increased at the same time and this summer Acer Capadoccicum, a highly decorative species in our arboretum, is being given the hornbeam treatment. Other species which are attacked, though not yet on this farm, include: beech, sycamore, poplar, sweet chestnut, oak and coniferous species, such as pine, larch and Norway spruce.

Peyton Hall 2008. Damage to field maple in young Plantation. Tree still alive.

In 2008, having rather belatedly leapt into action, we shot over 120 squirrels on our 200 acres. The received wisdom is that bark stripping only occurs when squirrel density rises above 2 per acre but, as can be seen by the numbers shot, the density on our acres must be vastly in excess of the safe level. The squirrels discard the outer bark and eat only the unlignified tissue beneath (i.e. the sap filled layers). It is believed by some to be an imitative process which can only be cured by clearing a whole area and hoping that the squirrels who recolonise it haven’t already caught the habit. The only method of achieving such a comprehensive clearance is by using warfarin which is rightly hedged about with all sorts of restrictions and could have dangerous consequences for other wildlife.

Peyton Hall 2008. Field maple. Leader ringed by squirrels. Subsequently broken off.

The grey squirrel problem in the UK has an almost exact parallel in New Zealand, where the bushtail possum was introduced from Australia, and has had a cataclysmic effect on New Zealand’s forest ecosystem. In Australia, the bushtail possum is protected and fits into an ecological background which has had millions of years to develop anti-possum strategies. But in New Zealand the possum has no natural enemies and has multiplied to such an extent that anti-possum poison is now ubiquitously nailed to trees and even dropped from helicopters. The New Zealanders seem better able than the British to overcome their political correctness and have developed a healthy attitude to exterminating possums. In Napier, in a museum devoted to the possum, I found a flattened, rather moth-eaten possum wedged under the back tyre of a dusty Mini and labelled “NZ road possum (squashed variety)”. My recent experiences have made me deeply understanding.

But perhaps salvation is at hand in the unlikely form of the current passion for TV celebrity chefs. Squirrels are good eating, there is plenty of meat on them, there is a recession on, and many of us may soon find ourselves having to live off the land. Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, the TV personality and chef, recently demonstrated on his programme the art of trapping and cooking squirrels. The hard work is in the skinning, but the programme delicately skipped that bit. Anyway, the results looked delicious. So if you want to beat them – eat them. Here is a recipe for “Squirrel Pie a la Peyton Hall”. (Cooking squirrel is very similar to cooking rabbit. The squirrel was delicious but we weren’t sure that the pigeon added much).

Take gun and shoot 4 squirrels. (And one pigeon if required). Take the breasts off the pigeon and skin the squirrels (N.B. squirrels are much harder to skin than rabbits).

Ingredients:

Pastry made from 12oz flour, 8oz butter (or use bought pastry)

4 squirrels

2 pigeon breasts (optional)

1/2 lb (200 grams) dry-cure unsmoked bacon lardons (or chopped streaky bacon)

4 fl. oz olive oil

2 medium onions, finely chopped

1 large carrot, roughly chopped

2 celery stalks, roughly chopped

1/2 lb mushrooms, sliced

1 1/2 pints red wine

About 1 1/4 pints stock (home-made if possible)

Salt and pepper

Pinch of dried mixed herbs, bay leaf, parsley

Beaten egg

Make pastry, wrap in cling film and put in fridge.

Heat half the olive oil in a heavy enamel casserole and fry the bacon lardons until lightly brown. Set on one side.

Fry the onions, carrot and celery until onions are cooked.

Put on one side with bacon. Add the rest of the oil to the pan and fry squirrel until brown.

Return the bacon and vegetables to the casserole, add the pigeon breasts if being used.

Add wine, and stock to cover.

Add seasoning, mixed herbs, bay leaf, some parsley stalks.

Cover casserole with lid and cook in medium oven for 1 hour.

Remove from oven and add mushrooms. Allow to cool.

Up to this stage can be done the day before.

Place pie funnel if you have one (or reversed egg cup) in middle of 3 pint pie dish.

Remove squirrel meat from the bone, slice the pigeon breasts and place in pie dish.

Take out bay leaf and parsley then add vegetables to pie.

Check seasoning of juice in the casserole and add enough of it to reach 1/2 inch from the top of the pie dish.

Cover with pastry and brush with beaten egg.

Bake in hot oven until pastry is cooked (about 45 minutes).

Serve with the remaining juice heated up as extra gravy.

Jeremy Hill

I started trying to persuade Jeremy to write an article for the magazine last summer, but he said he was not inspired. He seemed to get even less inspired as the world’s financial debacle unfolded and I thought we were going to get nothing. However on the 15th December the above arrived! Where would we be without Jeremy’s annual prose?