A Stay in a Nomad’s Tent

The high point of my 20 year career, spent restoring and buying handmade Oriental carpets, was a trip to south west Iran to visit the Qashqai nomads. When the live goat was brought out and slaughtered in my honour, I knew that this was no ordinary rug-buying trip. It had been an adventurous six and a half hour drive form the city of Shiraz to get to the nomads’ summer camp in the mountains. In the distance I’d seen a small cluster of people, the Qashqai nomads by their tents. It was an extraordinary sight, there were beehives everywhere and livestock milling around. I was one of the few European women that they had encountered, hence the goat’s demise at my arrival.

From childhood I have always enjoyed textiles, and since I became interested in carpets and rugs I have been drawn to the Qashqai. I find their rugs some of the most fascinating of all those made. They have their own character and style that I feel sets them apart and, as I have learnt more about the Qashqai people, I have found that this character is a reflection of their personalities.

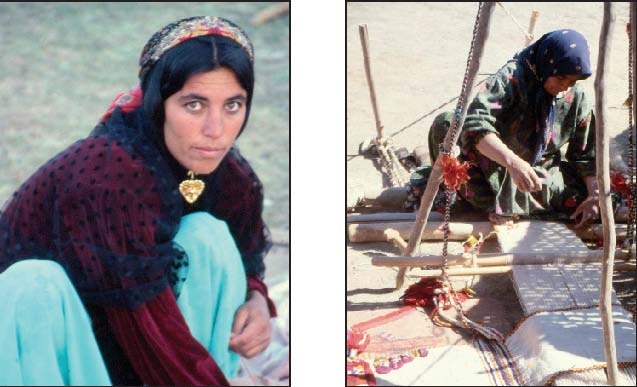

Qashqai tribal woman. Weaving a storage bag.

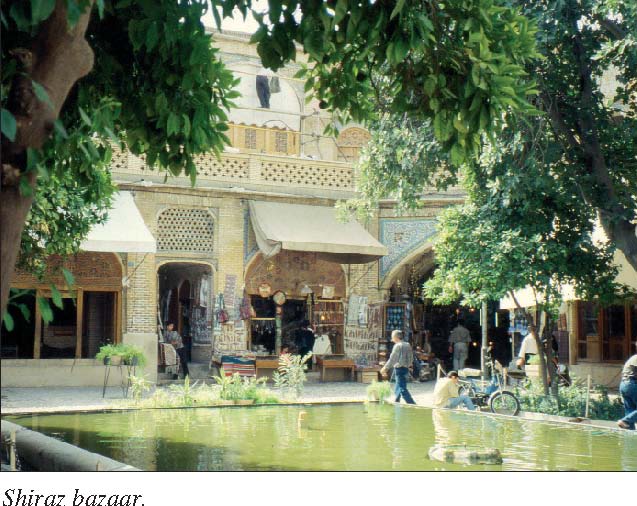

The area where the Qashqai live is known as the Fars province. The land has always been very important, linking the Persian Gulf and Tehran, which became the governmental capital of Iran at the end of the 18th century.

The Capital City of the Fars is Shiraz. This busy city with its huge bazaar is the main market and trading centre for the Qashqai. Running through the whole province is the massive Zagros mountain range. In the valleys and lowlands, the Qashqai have their winter camps. During their recent history much of this land has been developed by agriculturalists. The foothills and highlands of the mountain range, at altitudes of 1900-3300m, are where the Qashqai have their summer camps and main grazing for their livestock. At these camps they have cultivated small fields to grow wheat for bread making and animal feed. While settled during the winter and summer months, they will produce meat, honey, and other commodities, including carpets, to sell in Shiraz markets.

The Qashqai people themselves claim that their origins come from a diverse group from central Asia, the Caucasus north west of Iran, Iran itself and Turkey. Their ancestors are a mixed group of Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Persians, Baluchi and gypsies. Language and other evidence including symbols used in rug designs verify their diversity.

The Qashqai is a grouping of small tribes known as a Confederacy, which was formed in the late 18th Century when this diverse group of nomads and families organised themselves into a tribal structure. Their aim was to protect the natural resources of land and water available to them, their trade routes and markets and importantly, their migratory routes to and from their summer and winter farming and grazing land. By forming a large organised group, they were able to expand their territory and power.

The Khans were the most powerful group within the Qashqai. They had always ruled within the Iranian society and formed a large part of the Shiraz upper classes. They relied on the tribal organisation for military support, local policing, basic law and order and revenue in the form of tax collection. Historically, tribal society has had both a nomadic and settled element. As the Khans would probably live a settled and urban life, they would rely on the members of the Qashqai confederacy for labour within the home and on the land.

The second group within the tribe were advisors and heads of many of the sub tribes.

The third and largest group lived and farmed the land controlled by the Khans. Immediate families would live close together within a sub tribal group. Occasionally they would owe taxes to the leaders, but they were able to live independent lives.

The fourth group were hired labours and sheepherders, who would travel independently and would often be hired to help with the bi-annual migration.

The construction of the tribal group was formed by the people themselves. With good leadership, they had a great sense of solidarity and power from which they all benefited.

We arrived at the summer camp of the Shish-Buluki group. The core of the group was the families of four brothers living in approximately a two-mile square area. Each family had its own tent and livestock, and the tents were pitched quite a distance away from one another. In order to maximise privacy, the tents are placed so that they do not look in on one another. The group return to the same area each summer. A well has been dug for them by the local government, which is their main water supply. Unfortunately, due to the effect of global warming, the water supply is barely enough for the summer months. The stream that had run through the camp at the start of the summer had dried up and the grazing land was dry and parched.

We were the guests of the oldest brother. On our arrival we gave them gifts of sugar, rice and Calor gas. The sugar was in the form of a large cone that his elderly mother proceeded to break up into smaller lumps with some vicious looking pliers, and put into a beautifully woven bag to hang in the tent for storage.

We were invited to sit in the main tent and, as always in Iran, were offered tea to drink. The tent was neat and tidy and arranged in an ordered fashion. Before pitching their tents at the start of the summer the chosen spot is cleared and levelled. Then a low stone wall is built where the back wall of the tent will be. The tents are rectangular in shape and constructed from woven goat’s hair panels. The panels are stitched together to form the roof and three walls of the tent. The front wall is made from a lighter weight cotton canvas that can easily be put up or down, depending on the weather and time of day. The walls and roof are supported by wooden poles, which are tied in place by woven tent bands that are often decorated with tassels. On top of the low stone wall, all the family’s belongings, bedding and clothing is stored in woven storage bags. During the day, everything is packed away and covered with a decorative flat weave called a jijim. Depending on your position within the family or how honoured a guest you are, will determine your sitting position within the tent. The wall covered with decorative textiles acts as the perfect and most prestigious place to sit and look out over the flocks and pasture land.

Soon after we arrived, the father of the family carried the bleating goat past us. The preparation of food is simple and uncomplicated. While the goat is still alive its throat is cut so the heart can pump the blood out of its system. As there is no refrigeration the meat must be stored in the cleanest possible way. The blood is drained out of the animal to prevent the spread of bacteria. The butchering of the animal is done instantly. Almost every part of the animal is used, the skin being used as water bags. The men of the family cooked the meat on kebabs over an open fire.

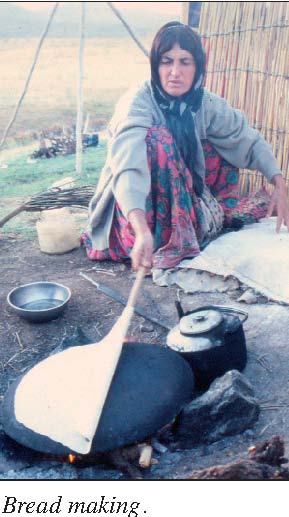

Bread making is also carried out over the open fire. A domed metal plate is placed over the fire to get hot. Small balls of dough made from flour, water and salt are kneaded, rolled and then flicked over the dome. As more flat breads are added, the pile is regularly turned so that the bread can cook evenly. Water is sprinkled over the bread regularly to prevent it getting too dry.

Another major method of food storage is in the form of a dough ball. These small balls, the size of marbles, are made from the boiled remains of the carcass and flour. While on migration this is often all the Qashqai will eat.

Otherwise, these balls can be diluted in water and act as a stock for stews and soups. Eaten on their own, I found them very strong and inedible.

Among the other food eaten by the Qashqa is honey from their own hives that they leave at their summer camps all year; a very strong goats’ cheese; and eggs that are collected each morning in small woven egg baskets.

When the water supply permits, and the climate allows, they will also grow vegetables, but the main ingredient of every meal is rice, which is bought in bulk during visits to the nearest market.

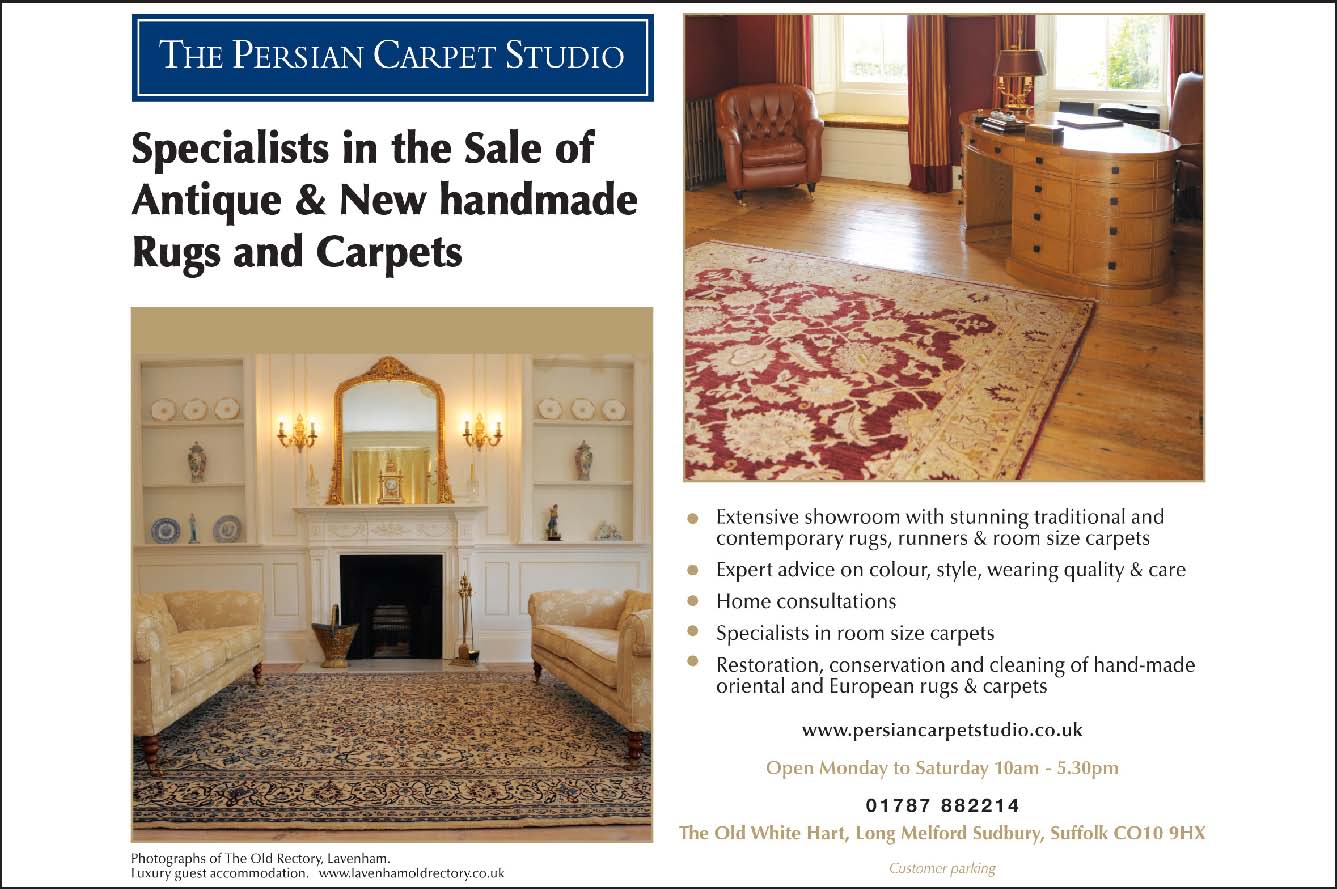

During my brief visit, I learned much more about the history of the Qashqai and the patterns and designs which they incorporate in their wonderful rugs. I always try to ensure that I have a good collection of both antique and contemporary examples in my shop, The Persian Carpet Studio in Long Melford. This is a busy, vibrant and thriving business that is regarded as one of the country’s leading retailers and restoration workshops.

Here we not only stock tribal rugs such as Qashqai, Turkoman, Belouch, and Kurdish, but also village and city rugs from all over Persia (Iran) as well as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkey and Morocco. There is nothing that gives our restorers more pleasure that cleaning and mending an old neglected tribal rug, and restoring it to its former glory.

It all seems a far cry from goat kebabs with the Qashqai nomads, but my work with rugs has taken me to places I would never have expected when I first started, and it is this unpredictability which has made it such a fascinating career.

Sara Barber

For details on carpets and their restoration contact The Persian Carpet Studio, Long Melford, Suffolk on 01787 882214. www.persiancarpetstudio.co.uk

Sara is the owner of the Persian Carpet Studio in Long Melford. Last year’s article will, I hope, have stopped people throwing away old rugs without checking with her whether they are of value. She has kindly placed another advertisement in this magazine this year. Do support her if you need a rug repaired. If you need to buy one, she has a marvellous selection in her studio in Long Melford.