THE STORY OF SPARROW’S FARM, GREAT HENNY – PART 2

Following the article about Sparrow’s Farm in 2014, I would like to explore some more of the history of the Farm in the 19th century and also describe the work to bring the farm into a productive state, as well as enhancing the wildlife conservation.

I have had an opportunity to research the history of the farm further; in particular to study Edmund Cook’s remarkable record of farming over 50 years between 1837 and 1887. This was recorded in his set of 50 annual account books which are preserved in the Essex Record Office. I also read the extensive study based on these records. This was carried out by Valerie Martindale in 1965 when she studied Edmund Cook’s farming practices and his success through different economic and farming conditions over more than half a century.

Sparrow’s Farmhouse from the west

Edmund Cook was born on 19th October 1804 at Sparrow’s Farm to Edmund and Mary Cook. He was the second child and had an elder sister, Sarah Anne, and a younger brother, Jacob Manning. The family had owned Sparrow’s Farm for several generations as his father Edmund Cook senior was born there. There is evidence that his grandfather, also Edmund Cook, ran the farm and extended the large kitchen and bakery to the north of the farmhouse (now Sparrows Cottage) in 1747. The initials E.C. 1747 are inscribed in the plasterwork in the attic now covered by a later addition to the building. This addition was possibly a cheese room, evidenced by the traces of extensive shelving in the room, which may have been used for maturing cheese.

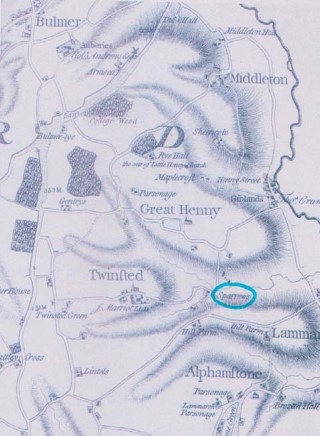

It is not known who built the large 10 bay barn at Sparrow’s Farm, but it was certainly central to the farming of the large acreage farmed by Edmund Cook, including Grove Farm, Sparrow’s Farm and parts of Hill Farm and Great Hagbush. The barn is listed as being 17th century, but expert opinion would make it possibly later than this so it could have been built by Edmund Cook’s father or grandfather. It certainly does not appear on the Chapman and Andre map of Essex published in I777 (see below), although this map is not detailed and is inaccurate about the topographical details of the local area. It is interesting that the farm remained in the Cook family until the death of Daphne Machin Goodall in 2008 at the age of 93. Her mother Margaret Goodall was a descendant of the Cook Family. It seems therefore likely that the family had owned the farm for at least 300 years or more.

Edmund Cook married Alice Pung, daughter of the widow Alice Pung of Grove Farm Great Henny, on 19th May 1835 when he was 30. The marriage set up Edmund very well, as the newly -weds were given Grove Farm, thus bringing Sparrow’s Farm and Grove Farm together as one holding. Further legacies and acquisitions led to Edmund Cook owning 237 acres, 0 roods and 39 poles and eventually with rented land farming 428 acres, 1 rood and 2 poles, hence his need for a large barn and additional stabling for the 16 horses needed to work the farm.

Original outside wall of Sparrow’s Cottage with initials ‘EC’ and date ‘1747’ – built by Edmund Cook’s Grandfather, also Edmund Cook.

Original outside wall of Sparrow’s Cottage with initials ‘EC’ and date ‘1747’ – built by Edmund Cook’s Grandfather, also Edmund Cook. Edmund Cook employed about 21 men; at that time the wages were 10s 6d per week for the best men down to 2s 6d for a boy. For example, he paid his head horseman John Braybrook 10s 6d and the other 4 horsemen, all from the Humm family, were paid 10s a week. Three horsemen were based at Sparrow’s farm, with 10 horses, and 2 at Grove Farm with 6 horses. The stables for the horses are still present adjoining the east side of Sparrow’s barn and there is a fine brick stable behind the farmhouse where the riding horses were kept.

At the time that Edmund Cook started farming in 1835, the country was just emerging from a serious agricultural depression which followed the farming prosperity of the Napoleonic wars. There was much unemployment among farm workers. Edmund Cook (senior) gave evidence about the Parish of Great Henny in 1834 to “His Majesty’s Commission for Enquiring into the Administration of the Poor Law”. He reported that in the Parish of Great Henny there were 40 more farm labourers than were needed on the farms in the village and that up to 20 men were, at times, in need of Parish relief. The impression from the account books is that Edmund Cook (junior) had the same men working for him for many years and that, although he did not pay the highest wages, he treated the men well and there is mention in his accounts of building cottages for them. He clearly liked having families working for him, as he employed 5 members of the Humm family and 3 members of the Tuffin family amongst his workers.

Edmund Cook ran a mixed farm, although he had mostly arable land. He also kept a considerable number of sheep, cattle and pigs as well as the horses, which provided the motive power on the farm. At Michaelmas 1837, when he began his farm accounts, he had 142 ewes, 91 lambs, 3 cows and 32 Steers, 64 pigs including 8 breeding sows. There is mention of him having 44 acres of pastureland, which would be a rather small amount of land to keep this number of animals, especially taking into account the need for winter feed. Edmund Cook operated a 4 year rotation of crops contrasting with the modern 3 year rotation. The rotation followed the following sequence: 1st year Barley, Rye or Oats; 2nd year Roots (turnips or mangolds); 3rd year Wheat; 4th year Clover, although this was also varied with beans. It is likely that he was able to graze his animals on the clover crop part of the rotation as he would have about 90 acres of this each year. This explains why he was able to keep quite a large number of livestock and sell a good number each year. As agricultural conditions deteriorated after 1870 from the previous good years, he increased the amount of sheep and cattle and decreased the arable land.

In each Farm account book Edmund Cook lists all his fields and the crops planted each year in line with his four year rotation. We have been interested to discover and use the old field names, which are recorded on the Parish Tithe maps, so we can follow what he was growing in the same fields more than 150 years ago. Many of the field names refer to the particular quality of the soil conditions in each field, while others have historical connections.

Sparrow’s Farm from Chapman and André map of Essex 1777.

We discovered that Leaden Croft is well named because it has a thick layer of heavy clay which becomes very heavy in the winter. Equally Swamper, being in the bottom of the valley, becomes wet and marshy; while Stonefield is dry and stony. Each field on the farm has a very different character as the soils change radically in a small area in the glaciated landscape. It seems that Cook had to employ a lot of labour on draining the fields, as during the year one man was engaged for many months on water furrowing which seemed to be a term used to describe digging and clearing field drains. We have certainly discovered how wet the fields become in the winter months.

One man spent several days a month catching rats, and a mole-catcher was employed for £6, 18s and 3d per year, dividing his time between Sparrow’s Farm and Grove Farm.

Looking at the records for each week, it is striking how much hard work had to go into hoeing the various crops in the days before chemical weed control. Equally, before Cook’s purchase of a threshing machine in 1857, many hours were spent each week throughout the year threshing and winnowing the crops. The beautiful old herringbone gault brick threshing floors survive in the barn midstreys where the large doors could be opened to provide a draught for winnowing the corn. On a trip to Ethiopia a few years ago, we saw exactly the same technique of winnowing the corn to separate it from the chaff by throwing it into the breeze.

When he purchased the Threshing Machine in 1857, Cook was one of the first farmers in the area to have one. It required a large number of men to keep it going, carrying water for the steam traction engine, feeding in the sheaves into the machine and stacking the straw. Then the threshing was carried out in concentrated periods rather than being spread throughout the year.

Edmund Cook continued his innovations in farming and, following the purchase of the threshing machine, in 1865 he acquired a Hornsby’s Patent Reaping and Mowing machine and a Boby’s Patent Corn Screening machine. These machines enabled the harvest to go much more quickly, although he still had the whole of the farm workforce doing the harvest but in a shorter time. It is noticeable that, in those days, the harvest began much later. In 1838, the harvest began on Monday 13th August and all the workers were fully engaged with this for 4 weeks. That year, the harvest brought in a total of £1,180, 7s, 4½d, which was the major income from the farm, although the livestock sold brought in an income of £627, 3s and 10d.

Apart from the 5 horsemen, one man spent all of his time looking after sheep of which there were about 230 in 1838. Edmund Cook does not relate the breed of sheep that he kept, but most likely they were Suffolk Sheep. He fed them on turnips in the winter. He mentions that the cows kept for milk were Alderney Cows (now an extinct breed) and he describes having Welsh Cows and Pollard Scots Cows. There is no mention of Suffolk Red Polls at that time.

Edmund Cook was generous in his gratitude for a successful harvest and he held a large harvest home party each year. In 1848 he entertained 178 people – 71 men, 71 women and 36 children. A large tent was erected to house the party. Each man was allowed 6 pints of beer and each boy 4 pints, so it would have been a lively event. He does not record what the ladies had to drink. He provided a generous meal of mutton and a pudding. The whole party cost him £29, 0s, 7d.

As Sparrow’s Farm is heavily wooded and contains damp meadows and a variety of soils, and had not been farmed actively for many years, in Daphne Machin-Goodall’s old age it became overgrown with a richness of wildlife. Bat surveys have showed the presence of colonies of Daubenton’s bats, barbastelle bats and noctule bats (our largest native species), as well as the more common pipistrelle bats. In the summer months, we are visited by the hobby, which is fast enough to hunt the noctule bats when they come out at dusk and can hunt swifts and swallows on the wing. We have a resident pair of buzzards who are nesting locally and always to be heard calling over the meadows. This winter there have been a number of snipe in the wet meadows and we have seen woodcock in flight.

Woldsman Admiral, the Red Poll bull, at Sparrow’s Farm.

On the north of the farm, there is an area of ancient woodland called Nub Hill, which contains great pollard oaks and is rich in bluebells and dog’s mercury, a species indicative of ancient woodland. The overgrown wood and scrub land is an ideal habitat for nightingales and, in May, up to six males can be heard singing; the more experienced singers outdoing the younger males with the richness of their song.

At Bures Mill, we have established a regular pattern of school visits from Bures Primary School and other local schools, where there is an interest in farming and natural history as well as the history of farming. We hope we will be able to extend these farm visits to Sparrow’s Farm, because of the interest of a traditional farm and the variety of the wildlife.

Red Poll cows and calves at Sparrow’s Farm.

The small herd of Red Poll cows has thrived well at Sparrow’s Farm and we have extended the shelter sheds on the back of the barn to accommodate them for the winter months, when the land is too wet. The winter feeding of the cattle has required us to put down proper hard tracks around the barn to prevent the vehicles becoming bogged down in the wet ground during winter. Sparrow’s Barn has proved an excellent place for lambing and, last year, we had 120 sheep lambing ( Llanwenog ewes and Welsh Mountain Mules) in the whole of the barn, with 240 lambs born in that period with very small losses. The Red Poll cows have produced some fine calves, which have been sold to Norfolk and Aberdeenshire.

The fencing on the farm was derelict and we have now managed to re-fence all the fields. This has required about 9½km of fencing and 28 new wooden field gates. We have used chestnut for the fence stakes and, in many places, alders for straining posts. We are grateful to the Chambers brothers of Bures for their excellent work on the fencing, and on weatherproof tracks and yards. The fencing has required us to cut back large areas of brambles, which had invaded the field edges by as much as 10-15 yards. We have also cleared back some of the invasion of alder trees from the wet Loshes Meadow, although we have left several acres under a thick growth of alders. We have cleared many ditches, which have been silted up and filled with the spoil from the numerous badger sets.

We have planted 800 metres of new hedging to replace hedges which had deteriorated or were grubbed out in the past. We have used a mixture of native hedging, including a lot of hazel as well as the usual hawthorn, blackthorn, spindle, dog rose and field maple. We have included hazel to encourage the dormouse population and we have planted hazel in the areas of woodland, too. In addition, we have planted 200-300 trees in the areas of woodland and are felling the Norway Spruce conifers in the overgrown plantation to encourage the mixed deciduous trees. We have planted more trees in the ancient Nub Hill woodland to replace areas that had become bare and overgrown with elder scrub. We are in the process of erecting barn owl nesting boxes, as we have a regular visiting population of barn owls. We have also planted a dozen black poplars from local stock in very wet areas at the bottom of the valley. All the new hedging planted last winter has made good growth. As we have learned from our experience of hedge planting at Bures, it is important to provide the hedge with a heavy mulch of wood chippings to give it a chance against the strong competition from hedgerow weeds – particularly nettles. The fields at Sparrow’s Farm have benefited from being grazed by the sheep, particularly the Hebridean Sheep who have a predilection for ragwort and docks, but ragwort remains a problem that is not easily eradicated.

We have learned a lot about how to manage the land and reading Edmund Cook’s account books has helped us to understand how to farm it. In contrast to him, we will have very little arable land and much help from machinery. We hope to find the right balance of sheep and cattle and to allow the natural meadows to flourish. We have moved on considerably in the last year, but there are still many tasks to tackle to bring the farm and its buildings into a good shape for the future.

Nicholas Temple

Last year, Nick Temple, gave us a first glimpse into the farm he had bought in Great Henny. I had driven past the house on several occasions over the years, and I felt sure that more lay behind what was visible, as has now been shown. I am sure there is a lot more that will be discovered in the future. Nick has previously written about Bures Mill, where he lives.