Sudbury New Town – c.1330

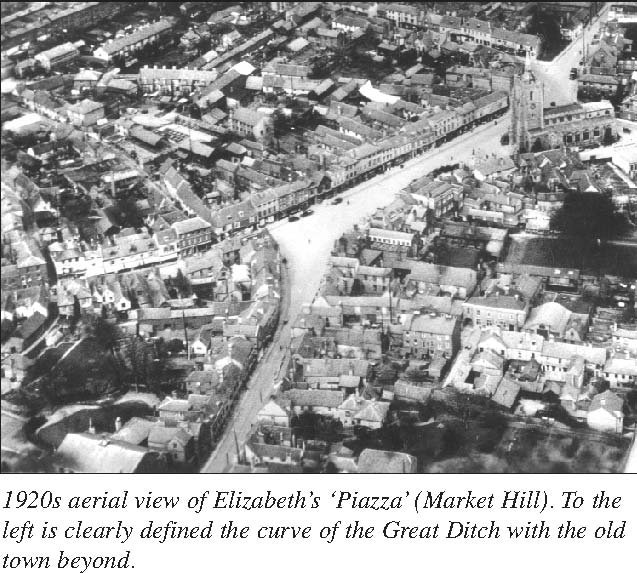

At the close of the 13th Century the town of Sudbury was still mainly contained within its Saxon Great Ditch. There had been the creation of a southern suburb by the Earl of Gloucester in the previous century when the first Ballingdon Bridge was built to give access to Essex and London, but otherwise the town was ‘bursting at the seams’. It had come into the possession of the de Clare family through the marriage of Amicia Gloucester to Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford, around 1182. The de Clare family gained their Gloucester title through this union and by and large proved to be remarkably generous as Lords of the Manor. The townsmen acquired a good deal of autonomy over the years with their new Lords keeping close contact through their steward at the Manor of Wood Hall just outside the town.

Sudbury had become a prosperous market town and an important centre of the Stour Valley cloth trade, but if this prosperity was to continue it was essential that the town was allowed to expand. In 1314 the male line of the de Clare family became extinct with the death, at Bannockburn, of Gilbert, who was only twenty-two and unmarried. One can imagine the consternation and shock to the townsmen when this news was received.

They need not have worried. The earl’s fortune was divided between his three sisters with Sudbury becoming the property of Elizabeth de Burgh. This thrice married sister was extremely wealthy, with an estimated annual disposable income of £3,000, a huge amount in those days. Having provided each of her husbands with a child and thrice widowed, she took a vow of chastity and settled down to enjoy spending her money wisely. She was a grandchild of Edward I, with close royal connections, and the Crown was ready with good advisors, both legal and financial, which stood her in great stead. Chief among them was Sir Robert de Bures who had carried out numerous commissions for the King and whose magnificent funeral brass, the finest military example in the country, is in Acton Church.

It took a little while to sort out the Clare settlement but once this was done the pressing problem of Sudbury’s expansion could be dealt with. One can detect the military mind of Robert de Bures and the aesthetically pleasing touch of Elizabeth in the brilliant solution they arrived at. This was to be no ordinary expansion but a carefully designed new trading centre built around and incorporating the field which was the site of the three annual trading fairs which were such an important part of Sudbury’s prosperity. This field was immediately outside the East Gate of the town and is easily identified today as Market Hill.

The new plan was to conserve the fair site as a prestigious trading area in the form of an open piazza. Two sides would have buildings with narrow frontages to the street and long extensions to the rear. The actual market place was to be to the north and south beyond this piazza-style square, thus forming a ‘T’ Shape. To the west, the square would open up in two directions towards the old town, just as it does today with Friar Street and Gainsborough Street. Between these two streets, and forming the square’s west side, would be built a large Inn which would become known as The White Hart.

The master-stroke would be the re-siting of the chapel of St. Peter from inside the old town to the east side of the new square. This would be built on a large scale with a tall tower. As a chapel of ease it would have no burial ground, but there would be a processional route protected against the walls. This processional route would pass under the tower, the ground floor of which would provide an open covered space for clerks and scribes to conduct legal business. However, this feature would be lost with a later expansion to the church when the aisles would be extended to embrace the tower and the clerks were given a new south porch with a chamber over.

The north side of this splendid building would form a backdrop to the new poultry and butter-market, with an appropriate covered cross. There would be a reserved space for the shoemakers and leather-sellers. From this open market, an approach road from a new North Gate would be lined with permanent shops and houses, to be known as North Street.

To the east of the Market Place the new entrance to the town would be known as Wiganend and East Street. To the south-east of the new church would be another wide open trading area, down the centre of which would be the Butcher’s Shambles. This was given the name of Borehamgate. In later years the Shambles would be moved to a site nearer the Butter-market.

The new town trading area was carefully planned as three main open sites which, apart from being asthetically pleasing, limited the damage cause by any building catching fire, the curse of medieval timber-framed towns.

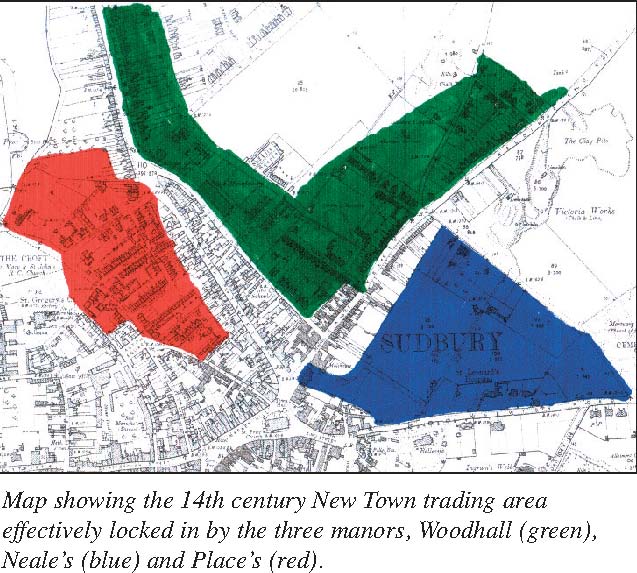

There was also another re-occurring problem of medieval towns owned by absentee landlords, that of encroachment on manorial sites. At Sudbury, where the new trading centre was surrounded by the Manor of Woodhall, this problem was dealt with by the introduction of clearly marked boundaries. The creation of two new manors, and the long-standing shackage rights of the freemen, effectively defined the extent of the trading area until the middle of the 19th century.

The two new Manors, Neale’s and Place’s were created and sold on 900 year leases. In the 1370s Simon of Sudbury, then Bishop of London, acquired Place’s for his newly founded St. Gregory’s College. After its closure by Henry VIII, the College and all its possessions were granted to the Paston family in Norfolk. Gradually Place’s was dispersed by different owners of the College, and when that was eventually sold to become a Workhouse in the 19th century what little remained of the Manor went with it.

Only in the past year have we been able to trace the full extent of the Places Manor. What is remarkable is the fact that its boundary can be walked with ease today. For many years it formed market gardens and small crofts. Gradually it was given over to Silk Weaving terraces and houses, many which have been demolished to make way for North Street car park. New Street, Gainsborough Road and the Beconsfield Estate cover the remainder.

Neales Manor

Neales suffered a similar fate passing through various owners and gradually dispersed. The Manor house, overlooking the Butter-market, was rebuilt in the early 19th century and is remembered today as East House. The Post Office now stands on its site. The manor stretched behind it and towards the east to what is now Constitution Hill. St. Leonard’s Hospital was built on part of it and Newton Road marks the boundary up to the Cemetery.

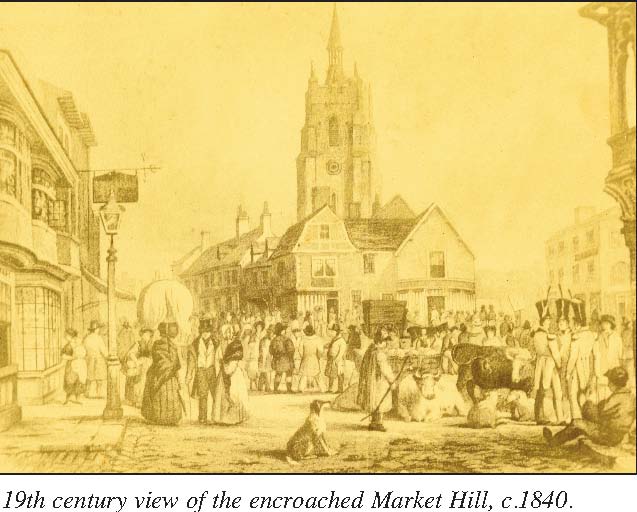

Nevertheless, in spite of all the precautions to prevent it happening, Elizabeth de Burgh’s New Town did not escape encroachment. During the 16th century, houses were built encircling the church which seriously reduced the market area. The annual fairs were removed to The Croft when the town was presented with it in the late 14th century. The piazza then became the site for the new Moot Hall in Mary’s reign.

It was the early 19th century Mayor of Corporation who took matters in hand and did away with the encroachments by a special Act of Parliament. Elizabeth’s wonderful open spaces, which create the splendid shopping ambience which the town enjoys today, are restored. They give the town its special appeal and it works, but we shouldn’t wonder at it. After all, it was created by, and for, a 14th century shopaholic.

In recent times there have been well meaning attempts to ‘improve’ the town centre. Some people would like to see trees planted on the Market Hill but it should be avoided at all costs. It is Sudbury’s Civic Square and the site of a Market which has just celebrated over one thousand years of history.

© Barry Wall

Barry Wall was the founder of the Sudbury History Society and has twice been its Chairman.

He has written a definitive book on Sudbury, which now needs updating to include this latest discovery. The book is titled “Sudbury History and Guide” ISBN 9780752433172.