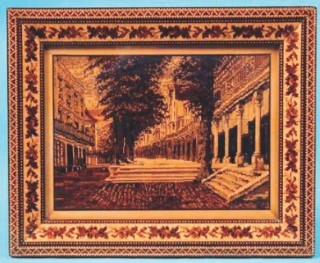

TUNBRIDGEWARE

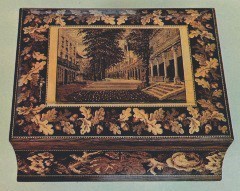

The Pantiles, Tunbridge Wells by H. Hollamby 1860

Tunbridgeware: Introduction The medicinal qualities of the Spa Spring at Tunbridge Wells were discovered early in the seventeenth century but it was not until after the restoration of Charles II that ‘spa fever’ gripped fashionable society. Expansion at Tunbridge Wells was particularly marked after 1680 and the area near the Well was laid out in the form of walks flanked by colonnaded buildings, where the places of amusement and the traders concentrated. The sale of fine decorated woodwares on these walks was first mentioned in 1697 by Celia Fiennes in her account of a tour round the country, during which she sampled the attractions of a number of spas.

The earliest instance of the use of the name ‘Tunbridge Ware’, however, was earlier, in 1686, in connection with production in London and it is probable that at this period the items on sale at Tunbridge Wells came with the traders who moved in for the season only, many from the capital. There is clear evidence of production in this Kentish town by about 1720. The identification of wares manufactured and sold as Tunbridge Ware in the period prior to about 1800 is difficult. This would appear to be because the name was applied – especially in London and south-east England – to all fine decorated woodwares which might appeal to an affluent clientele.

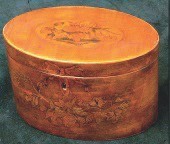

Confirmation of this comes in the form of an oval harewood tea caddy, circa 1790, decorated with floral marquetry and bearing the trade label of ‘Joseph Knight, Tunbridge Ware Maker to Her Majesty, Tunbridge Wells’. Items of this kind would not normally be thought of as Tunbridge Ware in the absence of such a label.

A similar harewood Tea Caddy

From the early nineteenth century the picture is clearer. The period to circa 1830 saw the development of two distinct types of Tunbridge Ware.

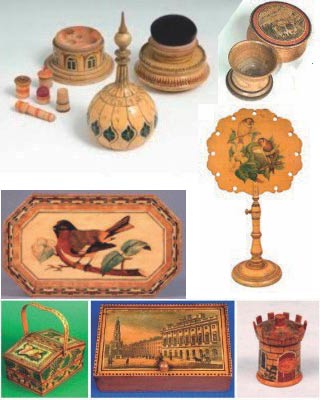

Whitewood Wares:

The first of these were whitewood wares, both latheturned items and boxes, decorated with paint or prints. George Wise of Tonbridge was a major supplier of these whitewood wares to East Kent resorts, while Brighton developed its own extensive industry.

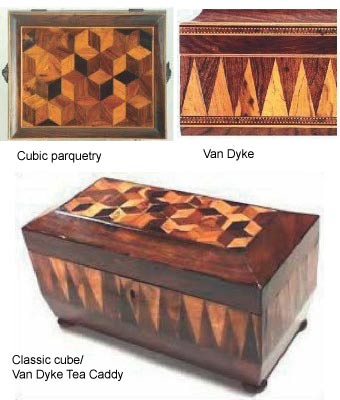

Parquetry:

The other type of ware to be developed during this period were boxes covered in cubic parquetry and with borders of contrasting triangular-shaped segments of dark and light wood known as Vandykes (after the artist’s famous beard).

Another form of parquetry composed of square, diamond and other geometrical shapes utilised to form borders and bandings, are found on wares of the 1830s and 1840s often in conjunction with early tesselated mosaic panels.

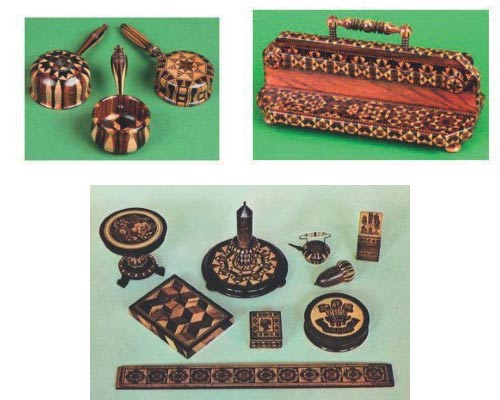

Stickware and half square mosaics were produced by assembling and gluing prepared sticks of triangular or lozenge cross-section, in contrasting woods, in bundles, often round a central plain wood core, which could be removed subsequently to produce hollow wares. The process was also used to produce patterned veneers for box decoration.

Examples of Stickware and some smaller items incorporating cube work:

Tesselated Mosaic: 1820s onward throughout the 19thC:

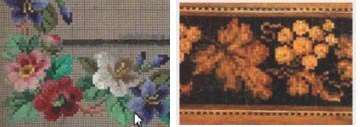

Said to have been invented by James Burrows in the late 1820s, the tessellated mosaic technique involved assembling slips of woods in bundles, following patterns drawn on squared (graph) paper. First a basic motif was selected and redrawn on the graph paper in polychrome, each colour representing the colour of wood to be selected. Alternatively an actual Berlin woolwork pattern might be used.

The selected woods were then glued together, sliced transversely and reassembled into secondary blocks, which could be cut into a series of identical veneers and applied to the item being produced. The Tunbridgeware manufacturers had a good selection of local woods available, such as oak, holly, yew, sycamore and maple, which they combined with a number of foreign timbers and were able to achieve a range of colours, including green, which was obtained from oak trees attacked by fungus. In the 1840s manufacturers had a choice of some 40 native and foreign woods; by the end of the century well over a 100 and in the 1920s the Tunbridge Wells Manufacturing Co. advertised about 180 different woods used in the mosaics.

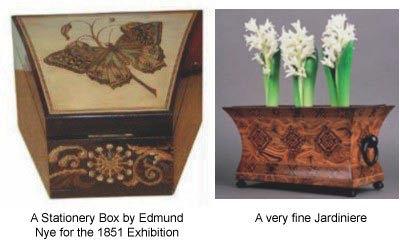

Size of tessera (each tiny square you see in a design) varies, the majority measuring about 1mm (0.04 inch) but there were a few veneers made in exceptionally large or small gauge. For the Great Exhibition of 1851 Edmund Nye displayed a sailing vessel made from 110,800 pieces (each measuring 3mm across). By contrast one of the butterfly panels on a bookstand contained 13,000 pieces, some scarcely 0.5mm in length.

Extraordinarily fine work can be seen in the portrait of Queen Victoria on the lids of the rarest top quality stamp boxes.

It is interesting to note that at almost the same time similar mosaic work was being developed in Italy in the neighbourhoods of Sorrento and Amalfi. Sorrento work is just as fine as Tunbridgeware but the geometric lines are often wavy and there is greater use of wood dyed in various colours. The designs obviously have an Italian flavour.

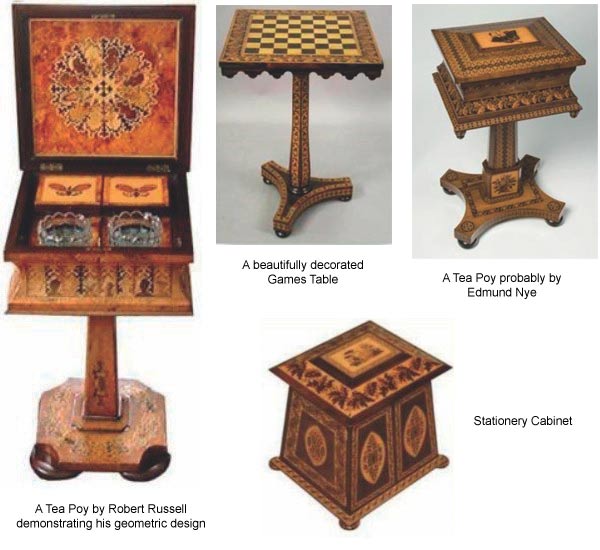

Examples of Tunbridgeware Mosaic:

One of most famous pieces is shown at the beginning of this article. It depicts the Pantiles in the centre of Tunbridge Wells. It is usually framed as a picture. Here the design has been incorporated in a fine workbox together with examples of the Berlin woolwork technique around the edges of the lid and base.

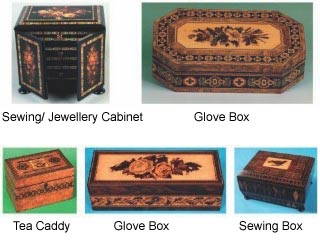

The most numerous products of the Tunbridge Ware industry were boxes. Tea Caddies, work boxes, games boxes and jewellery caskets are the most frequently found. Designs chosen were influenced by the popularity of Berlin woolwork embroideries at this period and, not surprisingly, bouquets and sprays of flowers feature frequently, with borders of floral, leaf or geometric nature. Rarer are shells.

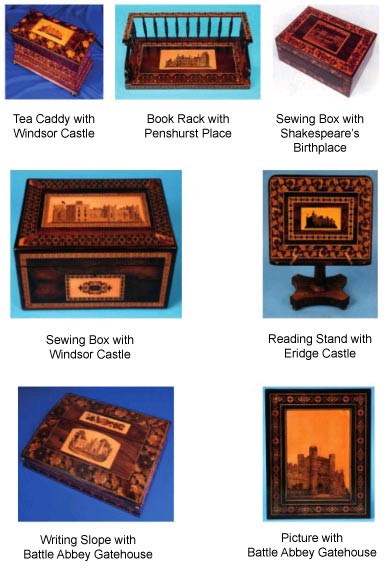

Views of castles, abbeys and country houses were depicted with great skill, particularly by Henry Hollamby. Views included Battle Abbey, Bayham Abbey, Dover Castle, Hever Castle, Tonbridge Castle, Eridge Castle, Windsor Castle and the Pantiles.

An indication of the extent of Henry Hollamby’s trade is to be found in the pieces decorated with views of Muckross Abbey and Glena Cottage, Killarney. Hollamby also used the mosaic technique to spell out on smaller boxes the name of resorts, or the purpose for which a box or item of ware was intended. Also of great interest is a stationery box decorated with the Prince of Wales’s feathers in mosaic, possibly by James and George Burrows – and several items depicting a boy in a kilt with a dog and parrot. These are believed to be an expression of the public interest in Queen Victoria’s eldest son, who was born in November 1841 and these designs must therefore date from the 1840s.

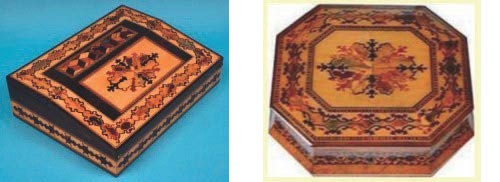

Examples of a different style of Tunbridgeware.

These items were made by Robert Russell who specialised in Geometric Marquetry design (similar to a jigsaw).

Boxes were not the only products of the industry, however. Other items include thermometers of the Cleopatra’s Needle pattern, combined thermometers and compasses of Henry Hollamby’s manufacture, pin cushions, pin poppets, thread spools, ink stands, paper knives, rulers, cribbage boards etc.

Particularly rare are such items as the Bilboquet Cup and Ball game, spinning tops, tape book markers and fine Bezique marker and card boxes.

Most of the items of this period were manufactured at either Tunbridge Wells or Tonbridge and the trade labels of Edmund Nye and Thomas Barton his successor, are to be found on a number of the more desirable items. Rarer are the labels of William Upton, one of the last of the Brighton makers. The finest period of Tunbridge ware production was between 1840 and 1890. The business of George Wise Jnr. closed in the mid 1870s, that of Henry Hollamby in 1891 and Thomas Barton died in 1903.

Barton’s business did, however, carry on trading until circa 1910, conducted by his nieces.

After circa 1910 the only maker remaining was the partnership of Boyce, Brown and Kemp. From 1916 the business passed through a number of hands in quick succession before taking on the guise of The Tunbridge Wells Manufacturing Co. between 1924 and its closure in 1927. The industry has never effectively been revived since this date in the Tunbridge Wells area.

I have demonstrated the minutest fraction of Tunbridgeware items that were made. The Tunbridge Wells Museum holds a large collection for further study. If any reader has an item with a castle which needs identifying I may be able to help.

Simon Foord

A tiny selection of very special examples: