THE UPS AND DOWNS OF A FLIGHT TO STELLENBOSCH AND BACK

Sometimes you read an article and think “I’d like to do something like that” and so it was in 2009 that Martin (a.k.a. Bear) Gosling decided to see if he and Annette could make an adventure of flying in their small plane, a Robin D400, to South Africa.

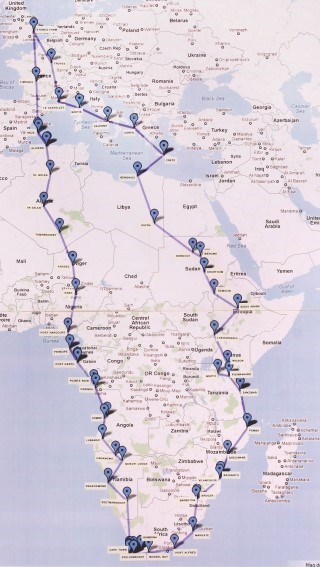

Bear had read of an ex- army pilot who had made a business of leading such adventures, and so it was that after much planning, Sam, who flew a Robinson R44 helicopter, and another seven aircraft gathered in Corfu in February 2011. The group consisted of a Turbine Engine Cessna 206, a Mooney, a twin engine Cessna Crusader, Bear and Annette’s Robin DR 400, an MCR 4, which had been built from a kit, and ran on car fuel! A Piper Archer, a Grumman AA5, and finally the leader in the Robinson R44 helicopter, christened “The Egg Whisk”.

Sam, the leader, had spent several months organising fuel at the more remote airfields in Africa, as well as organising accommodation along the way. Bear and Annette had left their private airstrip in Wickham St Paul’s on 5th February, flying via Troyes and Le Casstellet, in France, to refuel and from there on to Bastia in Corsica. From there it was on to Salerno to refuel, and then to the RV, in Corfu.

All the aircraft and their crews assembled on Friday 11th February, and were given a long and detailed briefing by Sam, and so the next day they all set off in the early morning, and were told by air traffic control to climb to 11,000ft, which is considerably higher than the normal flying height of 2,000 to 4,000ft. The first stop was Benghazi, and from there it was on to Kufra where bureaucratic delays meant two overnight stays in an appalling hotel. The next stop was Dongola in the Sudan, but take off from Kufra was delayed whilst awaiting permission to enter Sudan. During the flight Bear’s rev counter gave up, and could not be replaced until Stellenbosch, so instinct took over.

Refuelling at Dongola was from drums using a variety of pumps carried by each aircraft. From there it was on to Merowe, only to be told that passports had been improperly stamped on entry into Sudan and that “Entry Stamps” had to be obtained at Khartoum the next day. However the delay at Kufra meant that the reserved rooms were full with other guests, and the group were forced to sleep in a communal annex with the only loo a hole in the ground in a box shed in the yard, with a tap outside as the sole washroom.

Tuesday 15th saw the group delayed waiting for clearance to fly to Khartoum. However, when this was not forthcoming, it was decided to risk it, and all planes took off. On arrival all planes were made to park almost touching each other. Refuelling was from drums with a little man insisting it was his job. However in true British style, as soon as he was not looking, each pilot did the refuelling, and the little man admitted defeat.

Wednesday was a day off, and a visit was made to the Nile before the planned flight to Addis Abba in Ethiopia. Whilst the Mooney and Cessna would have range to fly direct, the other six aircraft would have to do a drum refuelling stop at Damazin in South Sudan. Khartoum airport is a very busy place, and delays in take-off meant that Bear’s engine overheated and had to be switched off to cool down.

Eventually six aircraft set off for Damazin, flying between the Blue and White Nile. Damazin turned out to be a dump of an airfield with potholes and cracked concrete. However there were a lot of official looking people waiting for the arrival of the British Ambassador.

After refuelling from drums all aircraft were ready for take-off. With four planes airborne and just the Cessna Crusader and the Grumman AA5 waiting, the Grumman came on the radio and announced that the Cessna had nose-dived into the runway. Fortunately it turned out to be the nose gear that had collapsed, but the plane had slid along the runway and was a write off and was blocking the runway for the Grumman and the British Ambassador, and his delegation. Sam, in the helicopter, returned to sort out the mess, whilst the others took three hours to reach Addis Abba only to discover that the fuel had not arrived.

Having located some fuel, only Ethiopian money would be accepted, so it was off to the Bank to change dollars into local currency, to return and be told that the fuel was not after all allowed for resale. After three days Sam came to the rescue having purchased some drums of avgas, hired a Cessna Caravan (a plane) and flown it to Addis. Having refuelled there was some urgency to get airborne as the next stop was in Kenya at a private airfield. However at this point two pilots mutinied and stayed behind, whilst Bear and the Mooney flew to Lokichoggio to refuel, before making a final dash to the private airfield at Barclay at a height of 7,000ft. However, with dusk fast approaching, they returned to Lokichoggio and spent the night in a camp for visiting pilots.

The following morning, Monday 21st February, the decision was made to fly direct to Nairobi to refuel and then on to Kilimanjaro in Tanzania to clear customs, before going on to the gravel strip serving the Serengeti. However the mutineers would have to fly to Zanzibar, and Sam was nowhere to be found. On Tuesday 22nd those of the group who had managed to get to the Serengeti strip went for a game drive, witnessing the amassing of thousands of Wildebeest for their annual migration. It was then back to the airstrip, and off to Zanzibar to be reunited with the others, including Sam, who had arrived by a commercial flight.

Evening drinks at the Serengeti camp.

The plan had been to depart on the morning of Wednesday 23rd February to go to the island of Barazuto off the coast of Mozambique, but once again clearance had not materialised so another night was spent in Zanzibar with a visit to an enormous market selling everything, and then on to the old slave market where the guide announced that he was one of twenty three children fathered from two wives and he in turn had eighty seven grandchildren.

Thursday 24th, still no clearances, however these came through the following morning, and so it was off to Pemba en route to Barazuto. A night was spent at Pemba Dive Bush camp, which was basic, to say the least, then the next morning it would be off, at last, to Barazuto. The Cessna 206 and the Mooney had a range of six hundred miles, but the rest of the group would need a refuelling stop at Qualimane which advised that it had avgas. However, when within radio contact of Qualimane advice came through that there was no avgas. Sam, once again, took charge and suggested a mix of fuel in the planes with mogas at a ratio of 50/50. The Piper Archer pilot refused to go down this route and said he would not budge. That left three planes, and one hundred and thirty five litres of fuel sourced in Qualimane, and which was shared out. Meanwhile Sam’s helicopter was in Beira, and as he was negotiating to go and buy fuel in Vilanculos a Cherokee 6 arrived, and the pilot said he had jerry cans of fuel in a shed, and Sam could buy some.

Sadly the many delays meant that the co-pilot of the Piper Archer had to go home, however the pilot was rescued by friends from South Africa, bringing fuel and a new co- pilot, but not until 4th March!

Monday 28th February saw the group leave Bazaruto to fly to Vilanculos some eight hundred miles from the final destination of Stellenbosch. Much to everyone’s surprise, Sam announced that he was returning home to fix the North bound sector, and the others would choose their own route to Stellenbosch. Bear routed via the Kruger as his entry point into South Africa. On landing he was told to empty his aeroplane. With a streak of stubbornness he refused, and told the officials that if they wanted it emptied, then they would have to do it. After a vain attempt they gave up.

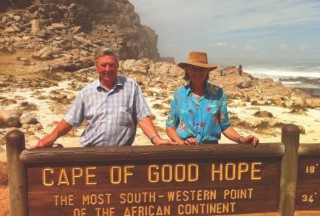

The next flight was a short hop to a legendary bush pilot’s airfield at Barberton and from there, the next day, it was on past Durban to Margate, for an overnight stay and refuelling. From there it was on to Mossel Bay and finally into Stellenbosch, twenty six days after leaving England and sixty five hours flying on the clock. On reaching Cape Town the helicopter was dismantled for shipment back home. The Robin DR400 was in need of a service and the replacement tacho cable. Bear and Annette explored Stellenbosch, and along the coast to Hermanus, and Cape Town and Cape Point.

The North bound route would be up the West coast, with a four hour flight to Keetmanshoop in Namibia, as an entry point. All planes left Stellenbosch for Cape Town International in order to clear exit formalities. However, when about to take off Bear noticed that his oil pressure gauge was dangerously low. As this had happened before, due to a poor earth connection, he decided to risk it and go, as all the other instruments were giving normal readings.

Keetmanshoop was devoid of everything, apart from the pre-ordered fuel. Customs were disappointed in the nil declarations and then immigration took an hour to turn up to stamp the passports. However, when it came to paying for the fuel, the credit card machine would not work, so in spite of offering the use of mobile phones, to get matters moving, credit card details were recorded and the group announced that as they had the fuel, they were off. Surprise, surprise, to be told that the credit card payments had miraculously gone through.

From Kleetmanshoop the flight took the group over the Namib Desert, which was picturesque with jagged ravines and seaweed like patterns in the bright orange sand. The destination was Walvis Bay where the controllers gave all pilots a dressing down for not obtaining permission to fly above 1,500ft. Finding the runway was a problem, as it was the same colour as the sand. However radio help was on hand, and saying find the golf course and you will see the runway!

Ruacana Falls in spate – Namibian border.

Once again, the intrepid group were reunited, as the Piper Archer had flown in from Qualimane with the new co- pilot, and meanwhile Sam had joined the Cessna 206 having returned from home, hopefully having fixed the return arrangements. The group left Swakopmund on Wednesday 16th March to fly to Mokuti Lodge airstrip, which serves The Etosha Game Reserve. The flight was a bit hairy, as cloud came down to 5,500ft and the land rose to 4,000ft. However these conditions only lasted for some fifty miles. An overnight stop was taken at the recently restored Mushara Lodge, where a game drive had been organised for the afternoon. There was a substantial amount of rain overnight, and, when the time came to leave, the sand runway was covered in puddles, so all elected to use the 500 yard concrete runway, and hope that they were airborne before it ran out. During the flight to the exit stop out of Namibia, at Ondangwa, they encountered the previous night’s rain. At Ondangwa planes were refuelled for the last time from a proper installation, rather than drums, which would be the order of the day until reaching Algiers. The next flight took a dog leg route to fly over the Ruacana Falls on the Namibia/Angola border, an awesome sight. It was then over the Etosha Salt Pans of Angola, a vast dried up lake of pure white salt. Elsewhere the countryside was flooded due to very unusual weather. Haven’t we heard that before in 2014? Then on to Lubango, at a height of 5,750ft, a night’s rest, then off once more to Sumbe, after another case of bureaucratic checks. Sumbe is two and a half hours north, and is a small coastal airfield with hills not far off the end of the Eastern edge. Three of the six aircraft had to abort their landings due to irregular wind currents, and the Mooney’s wheels locked less than ten yards from some sand dunes. After much checking and rechecking the officials allowed the group to depart for their hotel. The next day was a day off and a chance to visit some places of interest, such as a river crossing where slaves used to be loaded on to ships bound for Portugal and Brazil. The river here is now the local laundry with groups of twenty plus women washing clothes. From there, it was on to a small fishing village, where the fish are dried in the sun, to be sent to Zaire or Zambia. In Angola, by tradition, the women do all the work whilst the men watch TV, drink beer or joyride on motor cycles, also finding time to father offspring.

In the evening it was a serious briefing about the next day’s flight, as it involved avoiding at all costs, the (Un) Democratic Republic of Congo. The route was to an airfield at Cabinda, the exit point from Angola, and then on to Pointe Noir in the Republic of Congo. (Previously French Congo) Whilst refuelling, the pilot of the Mooney, noticed that one of the undercarriage doors was hanging down with a sheared linkage so the decision was taken to fly with the door open to Cabinda but this would use more fuel and so the other planes donated enough fuel for the Mooney to get to Port Gentil, as none would be available at Pointe Noir. Having arrived at Pointe Noir the Mooney undercarriage doors were given a temporary repair but when tested the next day, this failed. However, a search of a helicopter organisation on the airfield, produced a piece of steel of roughly the right thickness which was cut and drilled and taken off to be welded by a man on the side of the road using a large stone as his workbench. The Mooney was jacked up and the repair completed. The doors were then tested four times and the aeroplane was pronounced fit to fly.

Whilst the repairs were going on, the Mooney’s pilot had been calculating fuel requirements to get to Port Gentil in Gabon, and realised that he would need more than he had in his tanks, and since he could not use mogas the MCR4 donated his fuel which was replaced with mogas. Bear donated 25 litres of canned fuel, and another 45 litres from his tanks, which was replaced with mogas. Then it was on to Gabon some 300 miles, and Port Gentil, to discover that the fuel had not arrived. Surprise, surprise!

Bear and Annette at the Cape of Good Hope.

The next day Sam sent the Cessna and the MCR4 on ahead to the resort island of Principe, some one hundred and sixty five miles out to sea off the North West coast of Gabon. Meanwhile, those left behind waited, and waited, but still no fuel; that was Tuesday 22nd March. On the Wednesday, information arrived that the fuel, which was being brought from Cameroon, had reached the border, but the driver lacked a visa so a lorry had to be sent to collect the fuel, and take it to Libreville, where it would be transferred to a speed boat, but that had no fuel, and the driver had no money to buy any, so Sam transferred funds, and the boat set off for the eighty mile journey to Port Gentil, where the drums had to be floated ashore. The aircraft were refuelled and after a flight of an hour and a half, they reached the others, who had gone on ahead to the tiny island of Principe.

The next stop was Port Harcourt, where they would enter Nigeria – not a holiday destination on anyone’s list! After a two hour flight in poor visibility, they reached the coast, where they were made to stack before landing. To their relief, the fuel was waiting, and after refuelling there were more airport formalities, that took forever, until Sam finally managed to extract all the passports, and the group was ready to leave for the hotel. As this is Nigeria, two armed policemen with AK47s had been hired for protection. The driver of the people carrier announced that he was not stopping for anyone or anything, until he reached the hotel, and he drove at maximum speed sometimes on the wrong side of the road, but they were meant to be Police, and perhaps they thought that they were immortal, unlike their passengers, who were terrified.

The chosen hotel, The Bay Marriott Garden City Hotel, was given a minus star rating by the group, and was as uncomfortable as it could be.

The return journey to the airport was in daylight, which made it less frightening, and the group were relieved to get airborne by late morning, bound for Kano, four hundred and fifty miles North but still in Nigeria. Refuelling was carried out and the planes were parked on a vast concrete apron, to be told that that they had to be moved in case they were in the way of some dignatory. The hotel here was as bad as the previous night. The next morning, the weather forecast was appalling. However Sam went on ahead in the Cessna to Agadez, with a view to reporting back on conditions, and as the plane could use Jet A1 fuel, they could turn round and return, if necessary. Whilst Sam’s weather report was indifferent, the others decided that they had had enough of Nigeria, and took off for Agadez, flying three hundred miles, relying on instruments, and GPS, and locating the airport at 1,000ft. This is Niger, which is incredibly poor, but the group ended up in a Moroccan style oasis in the middle of nowhere – this was the Hotel Auberge d’Azel. Everything worked, even Wi-Fi.

The next day was Monday 28th March, again poor conditions, but the group set off for Tamanrasset, and as they approached the runway visibility improved, and the runway became visible from five miles out. It is both a civilian, and military airfield. Officials asked for forms in duplicate, but became hostile when the drums of fuel arrived. However, after assurances that the fuel was Algerian, and had been paid for, senior officials allowed refuelling.

The group were met by a Swiss lady, who had developed a tourist camp with her husband some twenty years previously. He had died, and she had married a camel breeder from Agadez in Niger. Her camp was simple – too simple for some, who opted out of the communal showers and loo blocks and went to a government hotel. The others stayed for a comfortable yet simple night.

The next day, saw an early start for El Golea, with a refuelling stop at In Salah, where a strong cross wind tested the pilots. Refuelling from drums went according to plan and then it was another two hundred miles to El Golea. The Mooney, being the lead aircraft, was told to land on Runway 10 but the others were told to use Runway 36. Runway 10 was blocked by the Mooney which had suffered a burst nose wheel whilst taxiing. Fortunately Bear had prudently brought two spare tubes. Whilst repairs were being carried out, the co-pilot of the Piper Archer was seen walking along the runway and, when asked why, said that his pilot had terrified him by not seeing a ten inch drop in the runway, and then ending up in sticky tar, halting the plane completely, and then having to be pulled out by a fire truck.

Once again the group found themselves in the only hotel, and it was another with a minus star rating. All rooms were unhygienic little boxes, with no bed linen as we know it, and the loo facilities were dreadful.

Out of Africa.

The group could not wait to leave for their final destination in Africa – Algiers. Overnight, the Mooneys tyre had deflated, but it was decided that the Piper Archer, the Grumman AA5 and the MCR4 should go ahead, and Bear, and the others would remain behind to help fix the Mooney. After much heaving and grunting the wheel was removed and taken into town to be repaired. Whilst this was going on, the other Mooney pilot discovered water in the fuel tanks and after much work the water was cleared. Just before lunch, the last three aircraft were ready to depart for the four hundred mile flight to Algiers, and a much awaited four star hotel. However the weather deteriorated, and the lead group had diverted to Bejia, one hundred miles along the East coast of Algiers. There was no avgas, and there was not enough fuel amongst the lead group to get to Algiers, and the second group was asked to bring what spare fuel they had, which could be shared around. As the Mooney had plenty of spare fuel, it went to Bejaia. The Cessna 206 also went ahead as it could be used to shuttle fuel from Algiers, if the need arose. Meanwhile Bear decided to go to Algiers, not without problems in making radio contact with the control tower, but a Scandinavian airliner came to the rescue and acted as a relay radio station. After a perfect landing Bear’s starboard wheel burst and he was stranded, meaning airliners had to divert around him. With much huffing and puffing going on, amongst airport officials, until the airport manager arrived, and managed to get a jack and lift the plane so that the tyre could be taken away for repair. Whilst this was going on, the other five aircraft landed, and smirked at Bear’s predicament. Eventually the tyre was brought back repaired, and the group left for the El Djazir Hotel. They had finally reached real five star accommodation, crisp clean sheets, clean towels, flushing loos and a good restaurant. This was the final night before the finishing post in Ibiza.

With the end in sight, it was foolish to think that all would go well on the final leg, however, the control tower failed to advise take off times for each aircraft, and only two could leave, whist the rest had to wait to be given new take-off slots from Brussels Euro Control! Eventually the final four aircraft left, relieved to be out of Africa.

After refuelling in Ibiza the group left for the Ocean Hotel where there was much hugging and kissing and champagne (Coke for Bear) followed by dinner and speeches from all. The next day was April Fool’s Day and Bear and Annette set off for, what looked like an easy final leg home, only to stop to refuel at Limoges, and be told that another flight plan was required by Toulouse, so an hour was lost, before finally reaching Wickham St Paul’s at 18.05. What an adventure, but not one for the faint hearted.

The group were away for 57 days, and visited 21 countries. Bear flew 120.15 hours. The longest leg was 4.05 hours. The maximum height was 11,500ft. Drum refuelling happened at 21 different airstrips and Bear’s aircraft used 4,673 litres of fuel.

Mark Dawson

When I suggested to Bear and Annette that they might like to write an article on their flight to and from Stellenbosch, South Africa, which would tie in well with an article on the Stellenbosch Wine Route, I had not expected to end up writing it! Bear had written a twenty one page A4 diary in small type, and I had to précis this down to some six pages. I hope you have enjoyed reading of an extraordinary adventure. Bear is the current British Air Racing Champion having won the competition in 2013.