A Walk Round Coggeshall Abbey

Front of the Tudor Manor House. Two storied Corridor and Abbots House.

When we have visiting groups, two questions are often asked. How long have you lived at the Abbey and why did you take it on as it is such a liability? The answer to the first question is ten years, and to the second, that my wife saw the building for the first time when she was buying asparagus. When she got home she told me that she had seen the most romantic house that she have ever come across with trees growing from the roof. I was duly persuaded to go and see it. I did not need much persuasion as I have always been interested in old properties and my curiosity is intense.

So we bought some potatoes and made a few discreet enquiries to ascertain whether the house was ever likely to come on the market. The answer was negative, so we continued on happily with our life at The Old Rectory, Fairstead. It was some years later when at breakfast one morning I opened Country Life and there for sale was the Abbey. I turned to my wife and boastfully said “Darling I will buy it for you”. Happily I was able to make a quick telephone to my eldest daughter and son-in-law who agreed to buy The Old Rectory, at Fairstead, which they had always admired.

Before we begin our walk, a little history and a few dates. The Abbey was founded by King Stephen and his wife Matilda in 1140. Originally it was a Savignac Abbey – a French order from Normandy. They were a breakaway movement from the Benedictines whom they thought had become too worldly. The Cistercians, and the Pope who was himself a Cistercian, encouraged the amalgamation of the two orders, and a Papal Bull was duly issued in 1148; thus 30 houses, 13 of which were in England, were taken over by the Cistercians. These white monks used the wool from their vast flocks of sheep to make their habits. Rievaulx Abbey had flocks of some 18,000 sheep. The Cistercian movement had been founded in 1098 at Citeaux which was surrounded by forests. It was the headquarters where the abbots gathered once a year to work out their strategy for the following 12 months.

The second Abbot of the Cistercians was Stephen Harding who wrote the rules that were to be adopted by all the Daughter Abbeys. Bernard, an aristocrat, joined the movement and brought with him three brothers and an uncle. Stephen obviously felt rather overwhelmed and sent them off to Clairvaux to found a daughter abbey.

By 1167 the Abbey Church, some 210 feet long, was completed and the high altar dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary and St. John the Baptist by Gilbert Foliot, Bishop of London. Much of the rest of the Abbey would have been completed by then, including the infirmary around which the Tudor house was built. St. Nicholas’s chapel was built in circa 1220 as the chapel outside the gate house. It was for guests of the Abbey and later became the parish church of Little Coggeshall.

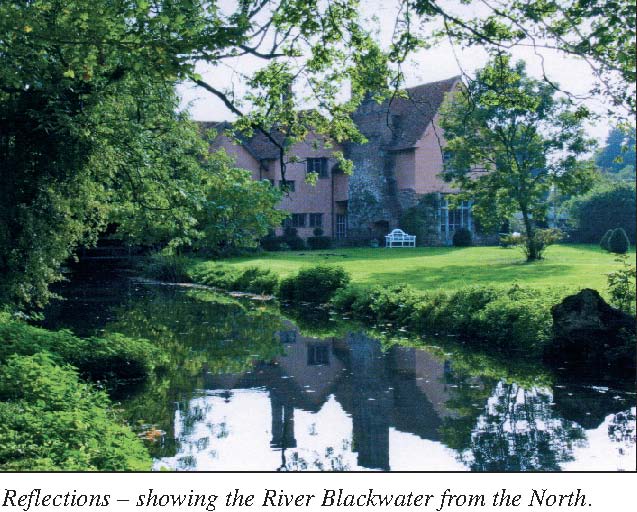

During the course of the first half of the 13th century the present course of the river Blackwater was constructed, possibly for three reasons. Firstly, to provide a head of water to drive the Abbey Mill. Secondly, to help overcome any flood problems – one side of the river bank is 3 inches lower then the other to enable the water to flow into the large water meadow. Thirdly, to make use of the canalised river, largely dug out by the lay monks, as a means of communication from the Abbey to Coggeshall with shallow punt-like boats.

In 1518 Sir John Sharpe had a lease with the Abbey for his mansion house. We shall see where this stood in due course – subsequently a 99 year lease was purchased by Clement Harleston for the same property in 1528. This lease was still held by Clement Harleston at the time of the Dissolution on 5th February 1538. He may have been responsible for saving the buildings that stand today, as the rest of the Abbey including the Abbey Church, Cloisters and Chapter House was ‘clene prostate’ by 1541.

The first owner was Thomas Seymour brother of King Henry VIII’s favourite wife Jane. He later married Henry VIII’s widow Catherine Parr. Both of them became guardians of Princess Elizabeth and, according to TV’s historical interpretation of Tudor times, Thomas can be seen chasing the Princess round her four poster! After his wife died in childbirth, he put himself forward as a suitor to the Privy Council for the Princess, but this was rejected. He became Lord High Admiral but lost his head for becoming involved in a plot. The execution order was duly signed by his brother, Protector Somerset, who in turn lost his head. Politics was a dangerous game in those days. Seymour had already handed back the property to the crown in 1541.

In 1581, Anne, the granddaughter of Thomas Paycocke, Coggeshall’s most famous wool merchant, acquired the crown lease with her husband, Richard Benyon. They had the wherewithal to totally restore the whole building and add new features. Since then it has largely remained the same except for gentle crumble.

Two other families need mentioning, firstly Mark Guyon, a rich wool merchant, who died in 1691 leaving ten manors to his two daughters. They duly married two brothers, members of the Bullock family, who owned several estates in Essex; the main one being Faulkbourne Hall, a large Tudor/Victorian mansion near Witham. Both daughters died young, one in childbirth with her child; the other when her child was still an infant. The child died at the same time.

The Bullock family always seem to marry into money but were eventually brought down by a Colonel Bullock who was father of the Commons. He had been a member for 54 years and was generous with his largess. He left debts of £20,000 in 1809, when he died. The Bullock’s auctioned the Abbey in 1880, and sold the Mill separately at the same time. At that time the Rev. Walter Trevelyan Bullock was living at the Abbey with his wife and eleven surviving children. The main residence, Faulkbourne Hall, was acquired in 1897 by the Parker family, who still live there.

Tour of the Abbey

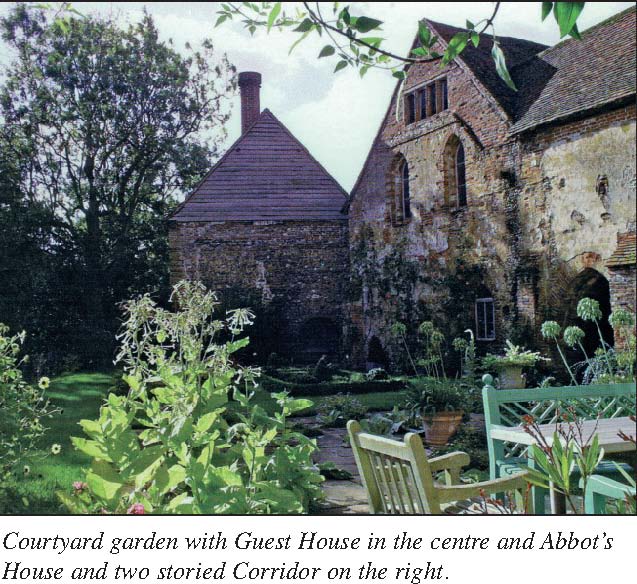

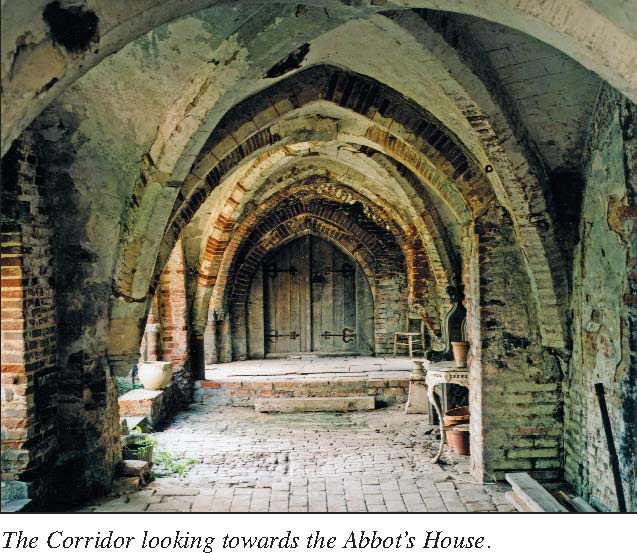

If it is a fine day we start in the Courtyard Garden with the river Blackwater running along one side, and with the Guest House, Abbot’s House and the East Wing of the Tudor Manor House completing the square. We look first at the two story corridor, built basically of rubble and flint but all the openings i.e. arches and windows are made of brick. The quadripartite vaulting are made of fine chamfered bricks supported by stone corbels which have worn and been reinforced by buttresses. At the time of construction, circa 1215-20, brick was a downmarket product. Abbeys were built of stone, so they rendered the vaulting and doorways, then limewashed and added lines to make it look like stone. The arches, made of roll moulded bricks, are quite superb.

Lee Prosser, Keeper of the Queen’s Palaces, suggested that the bricks were made by foreign workers on site as it was not until Tudor times that good British indigenous bricks were made. I confirmed this when the curator of an Abbey Museum in Belgium brought over a brick which was similar to our roll moulded ones but was made slightly later. The Cistercians, who were well organized, would send teams of builders and brickmakers to build an Abbey. They would then move on to another project which could be in a different European country.

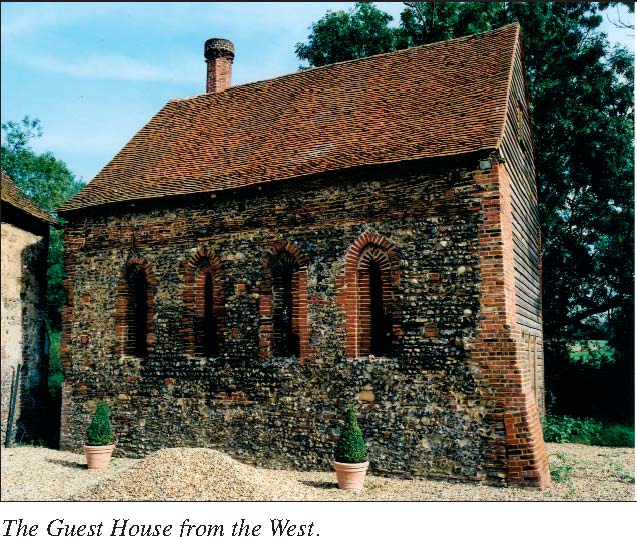

We then move onto the Guest House, which is entered through a splendid round headed Norman doorway.

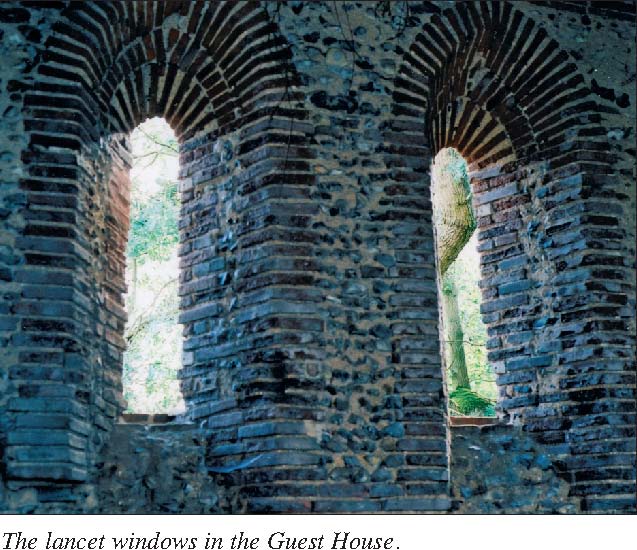

Coggeshall bricks are used for the quoins (corners). They are longer, wider and narrower than Tudor bricks. Inside, part of the tile on edge floor is still in evidence. The most striking element of the building is the lancet windows, with individual bricks used to produce a wonderful splay effect. They are thought to be unique. I have never come across anybody who has seen such work. Also of note are the Sedilia around the walls.

When the Paycockes arrived in 1581, all the roofs were raised and rebuilt. They do not have a central purlin but have wind braces instead. The south wall was removed and the building was used for secular purposes from 1581 onwards. The opening was filled up with Tudor bricked columns, and hung with doors. We replaced and repaired the columns using oak weather boarding for the wall. This building was built before 1190 and was originally approached from the east, rather than from the west as it is now.

We retrace our steps and continue out of the corridor and then to the entrance of the Abbot’s Chapel-Vestry. On the ground floor are stables and a storage room. We proceed up the outside wooden stairs into the large space which was formerly the Abbot’s Chapel and probably the Vestry. Perhaps the most noticeable thing here is the roof of circa 1585. It is the same construction as that in the guest house, but quite clearly with reused earlier timbers. The nib tiles in the roof are 13th century and pre-date the use of peg tiles. This makes them approximately 800 years old. There is a problem as to where exactly the Chapel was and which way it faced. If you look east there are two lancet windows and on the long south wall a Piscina for water. There is a lancet-shaped recess in the wall where it has been argued that a cross could have been placed. However, the Bishop of Brentwood on a recent visit, said that this would not have been the case. He thought that the opening was the Abbot’s Sedilia and felt that the Altar would not have been there. He did not appear to be concerned that the altar would not have faced east but faced north instead.

About a month later, a former Benedictine monk visited the Abbey. He is now an Anglican Priest, looks after six

small parishes near Cambridge, and lectures one day a week at Cambridge University on his specialized subject, The Cistercian Order. In the vacation he takes parties around Cistercian Abbeys, visiting about one hundred and fifty a year. When asked his thoughts on the matter he was very diplomatic, but on balance felt that the Altar would have faced east and the Sedilia like opening would have been a cupboard for storing the Chalice etc. You can take your choice, but I love the idea of the opening being the Abbot’s Sedilia and can visualise the abbots from around 1190 to 1538 sitting there. Would they have had a cushion and would it have been stuffed with wool or horsehair?

We now enter the Abbot’s sleeping quarters through the iron gates into the upper story of the corridor, and can see the bricks, tiles and a mill wheel and other stone capitals that have been rescued from the Abbey ruins. If we look at the floor at the north end, we can see that it is covered in Coggeshall bricks which must weigh a ton. On the west side is a lovely Tudor stable door, with the ironwork still intact. The door, when it was made well over four hundred years ago, after the Dissolution of the Monasteries, is of oak. The corridor would have been used to store hay and straw. It would have been reached by a ladder or wooden steps.

As we move out of the sleeping quarters we can see a roll mounded brick arch which still has its original rendering and limewash; this is because it has been protected from the weather for about 800 years.

We now climb down the stairs which our carpenter recently made of green oak to replace the rotten ones.

We pass the Guest house and observe the 18th century water mill which is still in working order and was last used commercially in the 1950s. It has a 19th century chimney. A steam engine (now removed) would have driven the machinery if there was not sufficient water to drive the millwheel .

If we walk a further 20 yards we come across the original course of the river now demoted, at least in terms of nomenclature, to the ‘Back Ditch’.

On the way back to the house we can see on the left a splendid low barn with wonderful curved braces. Lee Prosser has suggested that it could, however, have been a boat house and is very possibly early 14th century. Others argue that it could have been a cowshed and been late 15th or 16th century – as usual, experts disagree.

We now walk back past the other side of the corridor wall and can see where the Undercroft was and where the vaulting was sprung from the corbels to support the floor of the dormitory for twenty-four Monks. Then we reach the impressive Tudor porch which had a plaque, until recently: RAB 1581 (Richard and Anne Benyon). Further along, we pass a fine brick transom and mullion window which lights the hall. We now move round the north end of the Hall and see the fireplace and bread oven of Sir John Sharpe’s house. You can identify the outline of his house by the limewashed Coggeshall bricks. Above, these the Tudor bricks and four chimney stacks are very similar to those at Hampton Court. There are eleven hearths recorded at the Abbey in 1674, when the Hearth Tax was introduced. This would have been a very expensive tax for the owner.

If the weather is fine we cross over the bridge and look at the Abbey from the other side of the river. This is a wonderful view of all the Abbey buildings and also of the fine oriel window, which is early 17th century. If we have time we could look at the Abbot’s Stew Pond where the carp were kept; carp being the staple diet of the Monks. We have recently restored the main stew pond, as it was silted up and full of trees. This brings me to a splendid story. Since the Lateran council of 1215, when the bishops took back the control of parish churches, many of which had been run by the Abbeys, there had been much antagonism between the abbots and the Incumbent of St. Peters, the parish church. John, the Vicar of Coggeshall, was caught poaching from the Abbot’s Stew Pond. He was duly prosecuted in 1293 and sent to prison in Colchester jail. After three years his parishioners petitioned King Edward I, who ordered his release.

We now enter the house through the Tudor porch built by Richard and Anne Benyon in 1581. On the left is the hall, which has a splendid original fireplace which never smokes but uses a huge amount of wood. The beams of the ceiling are good quality chamfered oak. We found the original screen leaning against the wall of the Abbot’s House. Our carpenter collected the separate pieces and put them together, making and carving the missing areas. It was then erected in its original position.

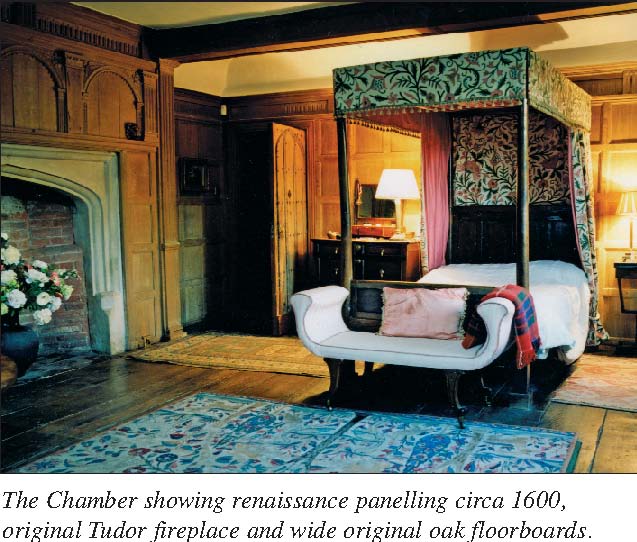

We now proceed upstairs to the chamber, which has exactly the same panelling as the hall with pilasters, spandrels and floral decoration. This room would have been used for special visitors. It has an original Tudor fire place and wide floor boards.

We end up in the large kitchen, which has two special features: a brick column, which supports an arch which was the top of the old Infirmary Building; and a very fine oriel window, which overlooks the river. The windows over the river have to be cleaned from a boat!!

Finally, I am frequently asked whether there are any ghosts. I have never seen one, but there was an unhappy Monk who was sent from Robertsbridge Abbey, having been found in a wood with an unmarried lady, and as a punishment he was banished to Coggeshall Abbey. After many years he wrote to Pope Benedict and asked for absolution. The Pope ordered him to be sent back to Robertsbridge and given his old cell back, together with his belongings. History does not relate whether he saw his lady love again.

Roger Hadlee

To book a group tour telephone 01376 561 246 or email the_abbey@tisicali.co.uk

For individual bookings, through Invitation to View telephone the Mercury Theatre Box Office 01206 573948 or www.invitationtoview.co.uk

Roger and Gill Hadlee live at the Abbey, which they have been restoring, after retiring from running an excellent picture gallery at the Royal Exchange in the City. The Abbey features on our website as a Place of Interest and is open to visitors who pre-book a tour.